When it comes to Pre-Columbian sexuality, there is unfortunately very little information available to us. David Bowles, a Chicano writer, recently summed up the situation very well in an excellent article on the topic (accessible here): “First off, it’s important to note we don’t and probably never will fully understand the attitudes of pre-Colombian Nahuas toward individuals we now call LGBTQ+ or their roles in Nahua society. The racist, sexist, homophobic, religiously intolerant lens of the Spanish obscures the particulars, leaving only a few tantalizing clues.” I recently stumbled upon one such clue in the book Fifth Sun by Camillia Townsend which I highly recommend as it provides a complete historical account of Tenochtitlan from the perspective of Indigenous people.

You can purchase Fifth Sun here:

In the book, an indigenous historian from the 1500s named Chimalpahin relays an extraordinary historical account that sheds considerable light upon Pre-Columbian sexuality. In the year 13-Reed (1479), The Chalca Tlalamanalca (residents of Chalco) arrived in Tencohtitlan for the first time to sing for the Mexica tlatoani Axayacatl. The musicians chose the song of the women of Chalco: the Cradle Song. Unfortunately the musicians played the song very poorly and a man by the name of Quecholcohuatzin who was standing nearby intervened by taking over the drumming and singing which greatly pleased Axayacatl who came out of his palace to join the dancers. Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina conquered the altepetl of Chalco in 1464 and according to Townsend, this particular song was carefully chosen as a form of subtle protest and an appeal to show mercy to Chalco. Chimalpahin referred to the song as both “the song of the women of chalco” and “song of the warrior women of Chalco.” Chimalpahin then goes on to say that the particular version of the song performed for Axayacatl was composed by a man named Aquiauhtzin Cuauhquiyahuacatztintli. When the song text provided by Chimalpahin is analyzed, it is clear that it bares striking similarities (but rearranged to reflect the political desires of Chalco) to another song titled “The Cradle Song” which was a song composed in Tenochtitlan and is written from the perspective of a “Mexica girl.” It is clear that the basis of “the Cradle Song” was much older and had many variations (which continued to be performed after the conquest at least until 1564) but all the variations share one central theme: a woman discussing her sexuality.

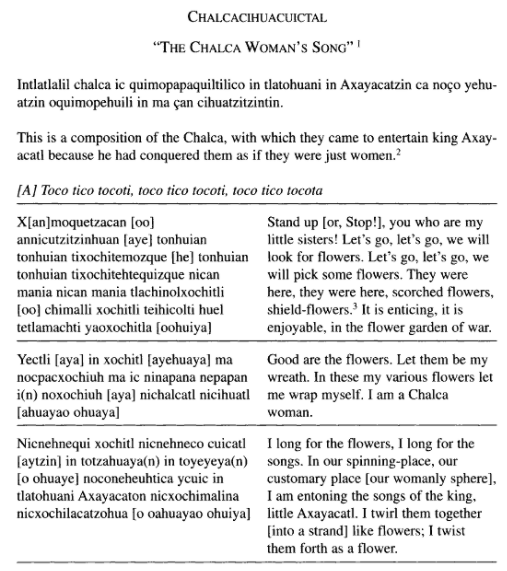

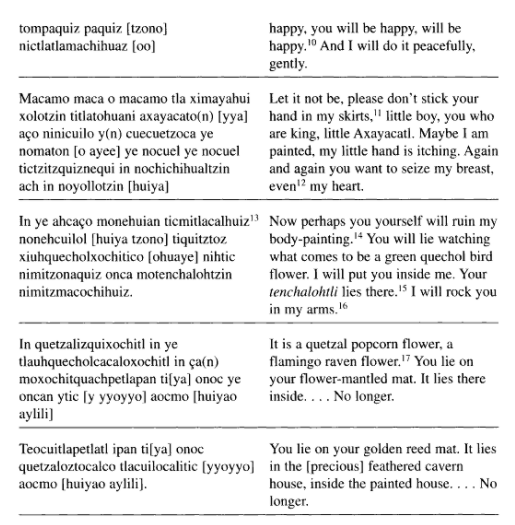

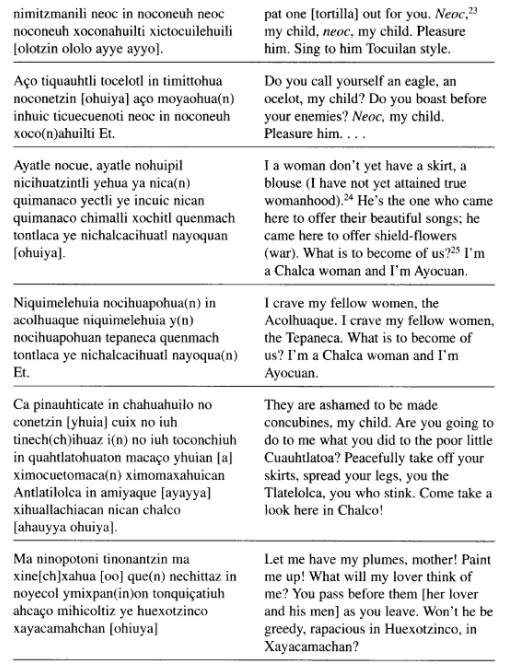

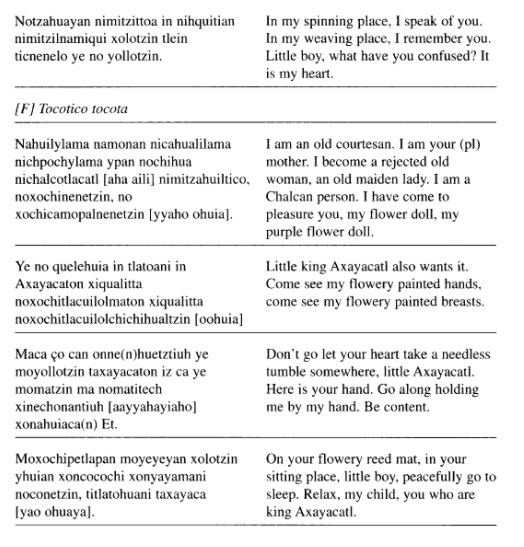

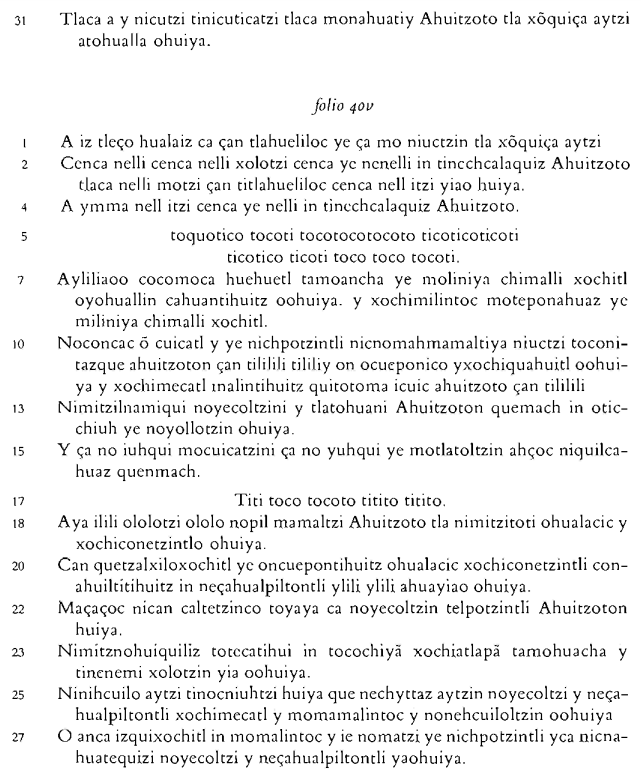

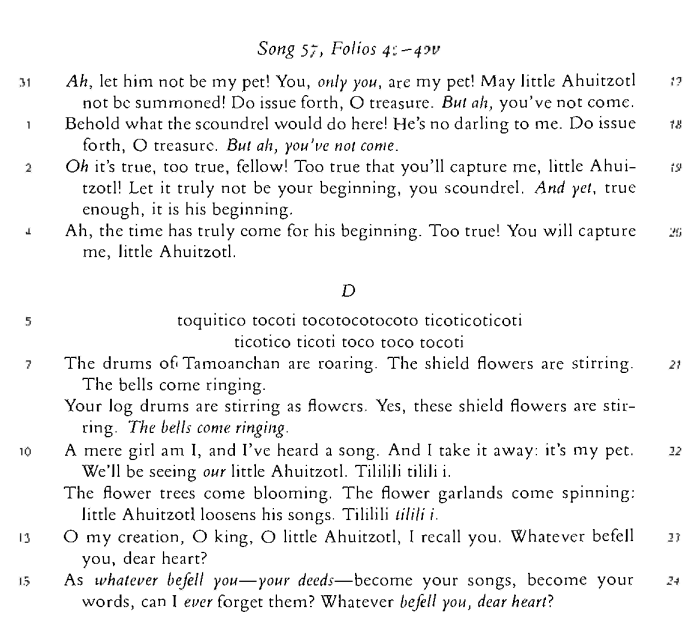

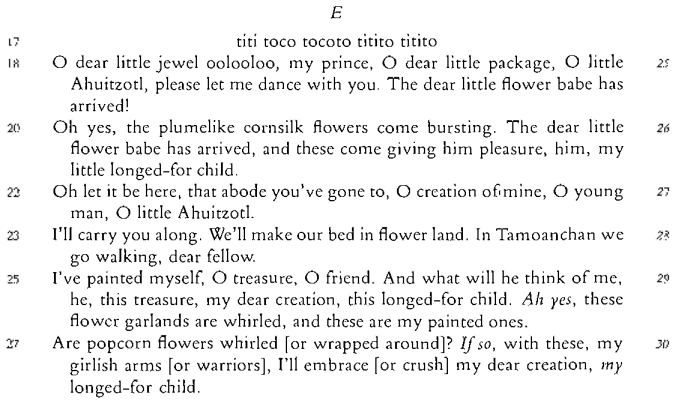

Here is the version of the song titled “Song of the Warrior Women of Chalco” that Aquiauhtzin Cuauhquiyahuacatztintli performed for Axayacatl translated by Townsend with the help of other Nahuatl scholars:

The Cantares Mexicanos by John Bierhorst is a critical translation of 91 Nahua songs that were documented in the 1500s. Most songs are clearly Post-Columbian (while still maintaining traditional Indigenous themes and structure and hence are immeasurably valuable), however a few such as the Cradlesong derive from Pre-Columbian compositions.

Unfortunately, the book is now out of print however you can download a pdf copy of the Cantares Mexicanos here

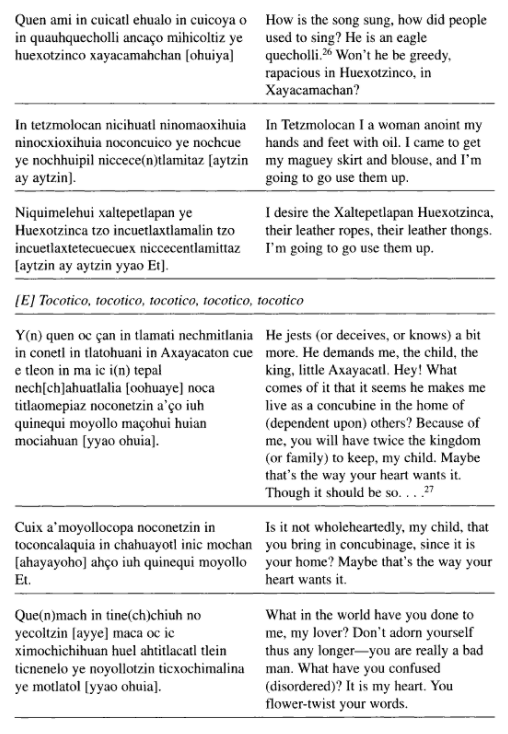

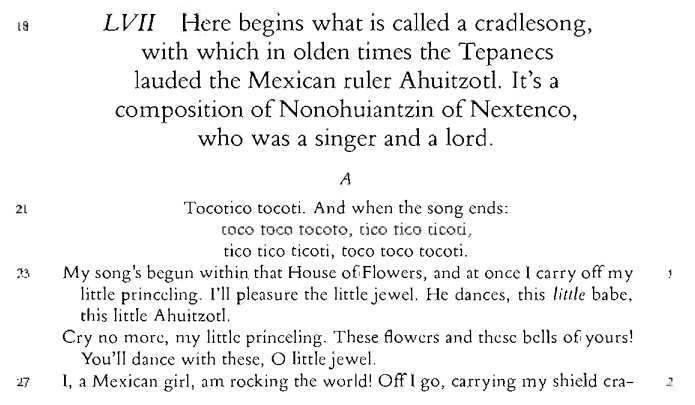

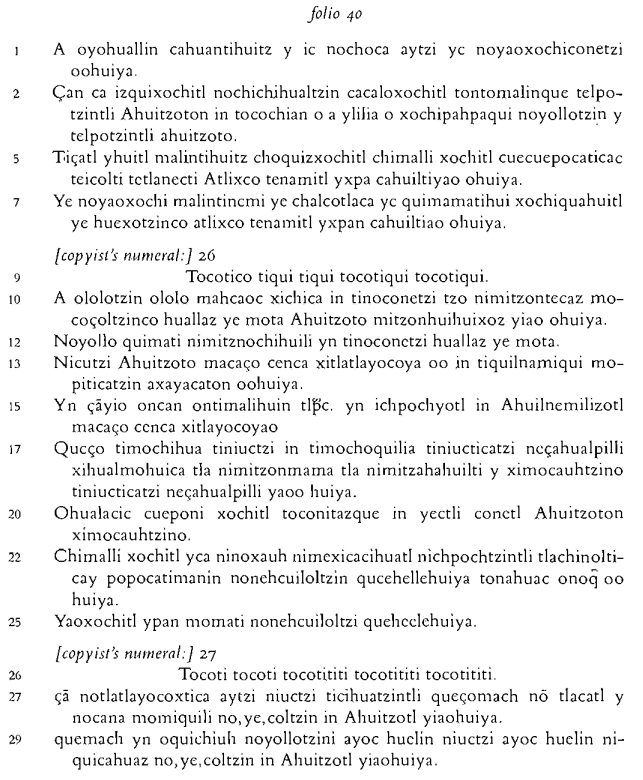

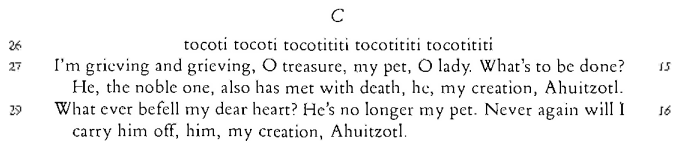

Here is a variation of the above song titled “The Cradlesong” this time performed by Tepaneca musicians for Tlatoani Ahuitzotl:

After the conquest, the perspective of males (both Spanish and Indigenous) dominated the historical discourse and it is very clear that the Spaniards successfully indoctrinated Native people very soon after the conquest so that we are left with only shreds of evidence here and there in which to reconstruct Pre-Columbian sexuality. As a result, these songs are invaluable as they provide an unparalleled view into sexuality from the very rare perspective of women. In the book the Fifth Sun, the author continues the story of the Chalca singers in Tenochtitlan with an equally tantalizing account that after Quecholcohuatzin was finished singing, Axayacatl was so impressed he invited him to his room where the two had sex.

Unfortunately, this historical account raises more questions than answers: Was the Cradle Song originally written by a woman although all of the authors listed were male? Does this song portray an accurate representation of womens’ sexuality in Pre-Columbian Mexico? Was the sex between Axayacatl and Quecholcohuatzin consensual or was it actually rape? Was the tlatoani the only one who was allowed to have homosexual encounters or was it accepted and more widespread? Regardless of the answers to these questions, it is clear that this historical account supports David Bowles’ analysis that there were clearly socially acceptable gender roles in Pre-Columbian society that did not fall in line with the official narrative that is today passed through the lens of 16th century Catholicism.

Permalink

Hey, btw, I did a verse translation a few years ago that catches nuances Bierhorst missed: http://davidbowles.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/cradlesong-bowles.pdf

Permalink

Great work brother – thank you very much for sharing!