Title: Xochimilco's sunken treasure

, By: Ayres, Alison, New Scientist, 02624079, 4/10/2004, Vol. 182, Issue

2442

Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors caught their first

glimpse of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in November 1519.

As they looked down from the mountains, the city appeared to float on

the surface of a vast, shimmering lake. The Spaniards thought they had

found another Venice, not realising that much of what they saw was reclaimed

land.

The Aztecs had created a labyrinth of islands in the lake with the help of their own sewage. These fertile mounds supported one of the most productive agricultural systems the world has ever seen — but Cortés took scant notice of that. Horrified by the ritual of human sacrifice, he captured and destroyed Tenochtitlán with great energy, and initiated the building of Mexico City on its ruins. Since then, one area of the original lake has resisted centuries of drainage. The floating gardens of Xochimilco are a reminder of Aztec ingenuity, and an ancient practice that might solve some of the modern city's sanitation problems.

TENOCHTITLAN, the wondrous Aztec capital city, lay in the Valley of Mexico, a vast landlocked basin surrounded by mountains thrown up by volcanic activity. When the Aztecs arrived in the valley in the 14th century, they found five great lakes. They chose to settle on the swamplands around Lake Texcoco and began to build themselves a city on a small island in the lake. It was an inhospitable, impractical location but they were following the directions of the god Huitzilopochtli, who had told them to build where they saw an eagle eating a snake perched on a cactus.

Pushed for space on their island, the Aztecs began to reclaim land from shallow regions of the lake. They piled up soil from the shore and sludge from the lake bed into rectangular wedges of land, or chinampas. The chinampas were up to 200 metres long but never more than 10 metres wide. The chinamperos, the farmers who cultivated the land, floated along the canals between them, tending the crops from their flat-bottomed canoes.

The chinampas were extraordinarily fertile. Seven crops could be harvested in one year and irrigation was unnecessary because water constantly seeped into the soil from the canals. The secret of their fertility was the Aztecs' sophisticated method of composting and mulching, sustained by the sludge at the bottom of the lake. Chinamperos would endlessly trawl the canals in their canoes, dragging up thick sediment from the bottom with a cloth sack on the end of a pole. They would then spread it on their land. Human faeces were part of the mix, so chinampas farming doubled up as Tenochtitlán's sewage treatment works. Most sewage went straight into the canals and became part of the sludge at the bottom. Some was spread directly on the soil and covered with sludge.

As the area of chinampas expanded, the Aztec city flourished. The artificial islands produced enough food for the city's 300,000 inhabitants — and a formidable army. The Aztec empire eventually spread to nearly every corner of present-day Mexico, but it lasted less than a century. Cortés and his conquistadors reached Mexico's shores early in 1519, and in 1521 conquered Tenochtitlán and razed the city.

The Spanish wasted no time importing their European style of construction to build Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec capital. They began to drain the lake to control flooding and create more land for building. The drainage continued over centuries, and thousands of hectares of chinampas disappeared.

Chinampas farming might have died out altogether were it not for the fact that one part of the lake at Xochimilco on the southern edge of Mexico City would never stay dry. Today, this area of some 30 square kilometres is all that remains of the original chinampas. It is home to descendants of the people of Tenochtitlán who speak the Aztec language Nahuatl and farm using the ancient methods.

In the early 1980s, a team of scientists working for an organisation called the Grupo de Tecnologia Alternativa (Alternative Technology Group) began to visit Xochimilco. They were trying to find cheap, sustainable ways to provide sanitation for some of Mexico's poorest people. The director of GTA, architect Josefina Mena Abraham, became intrigued by a tantalising feature of life at Xochimilco.

The modern chinamperos were still sending their sewage into the canals of Xochimilco, yet the water didn't stink and there were no problems with the kind of pathogens normally associated with human waste. The team began to sample sludge dredged up from the canals, taking it to their laboratories for analysis. One day, a student who had been sterilising equipment in an autoclave noticed that one microbe resisted the treatment, surviving a temperature of 220°C.

Among the bacteria living in the Xochimilco sludge was one that was thermophilic — a heat-loving microbe similar to those found in geothermal vent and hot springs. Mena Abraham was intrigued. Perhaps this unusual bacterium was the key to the Aztecs' success in dealing with their sewage and creating one of the most productive farming systems ever known. She asked Michael Cole, a soil microbiologist at the University of Illinois in Chicago, to take a closer look at it.

Cole found that the bacterium had several characteristics that would make it an excellent composter. It binds nitrogen, the most valuable nutrient in human waste. It neutralises dangerous pathogens in sewage, although no one yet knows how. And it speeds up the decomposition of organic waste.

Mena Abraham cultured the bacterium in her lab and the GTA began to think about how it could be incorporated into their designs for sustainable sewage treatment systems. "We wanted to be able to reproduce the characteristics of the sludge we had found at Xochimilco in a modern machine, and we wanted the bacteria to live and reproduce in that sludge," says Mena Abraham. She started work on a small-scale sewage treatment plant that mimicked the canals of Xochimilco.

The idea was to pipe sewage into a settling tank, with a layer of sludge at the bottom seeded with the chinampas bacteria. The bacteria would make the sewage safe and, at intervals, some of the mix would be vented from the tank into a compost bin filled with household scraps and garden waste. The bacteria would then go to work on this, producing a high-quality organic fertiliser made the same way as it was in Xochimilco. If conditions in the settlement tank were right, the bacteria in the sludge would quickly replace those removed to the compost bin.

But Mena Abraham couldn't help wondering why a heat-loving bacterium was living in the bed of Lake Texcoco. In her spare time, she started to research the longer sweep of history in the Valley of Mexico and discovered that around 2000 years ago a devastating drought had hit the region, drying out nearly all of the lakes for more than a thousand years. It had been caused by the eruption of Xitle, a nearby volcano, which must have showered the valley floor with debris. Mena Abraham believes this was the source of the bacterium.

The GTA has now developed a system for recycling organic waste, which it calls Sirdo. The system can be as simple as a composting toilet or a more complex sewage treatment plant serving an entire apartment block and producing a valuable by-product in the form of garden fertiliser. In both cases, the key ingredient is the bacterium from the chinampas.

When the Spanish arrived at Tenochtitlán, it was one of the largest cities in the world, yet it was noted for its cleanliness. Mexico City is one of the modern world's biggest cities — but its dirtiness is legendary. Mena Abraham believes it is time for its inhabitants to get back to their Aztec roots and learn a few lessons from Tenochtitlaán's chinampas.

~~~~~~~~

By Alison Ayres

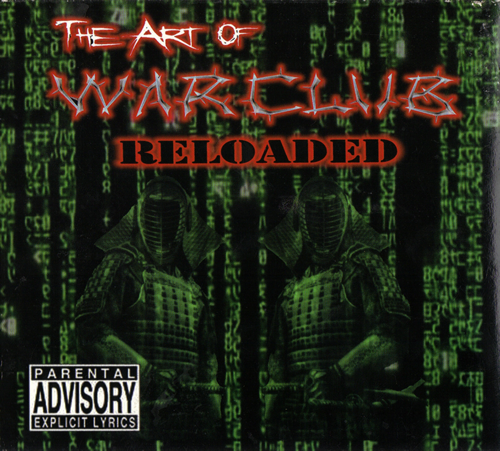

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06