Title: Oldest New World Writing Suggests Olmec Innovation , By: Stokstad,

Erik, Science, 00368075, 12/6/2002, Vol. 298, Issue 5600

Oldest New World Writing Suggests Olmec Innovation

Contents

The Olmec world

The mother culture?

Inscribed characters that resemble those used in the later Maya script

and calendar suggest that the Olmec were the first American scribes,

boosting the theory that they heavily influenced later cultures

In A.D. 738, a minor lord in what is now Guatemala pulled off a staggering victory: Cauac Sky of Quirigua captured a powerful king, known as “18 Rabbit,” beheaded him, and overran Copán, a major city in the Maya empire. Chronicled in inscriptions on numerous stone monuments at Quirigua, that upset is just one saga in a sweeping history recorded by the Maya in stone carvings for 7 centuries. Yet despite archaeologists' phenomenal success in deciphering Maya hieroglyphs, a fundamental aspect of this sophisticated civilization and its copious writings has always been a puzzle: their origins.

Scarce finds from pre-Maya times have left archaeologists arguing whether key features of Maya civilization, such as writing and the sacred calendar, stemmed from a nearby culture called the Olmec or whether several early cultures contributed. Now on page 1984, a team of archaeologists describes two artifacts that preserve signs of script: fragments of stone plaques and a cylindrical seal that bear symbols known as glyphs. Dated to about 650 B.C., these are potentially the oldest evidence of writing in the Americas. Mary Pohl of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her co-authors argue that one fragment names a king and a date, indicating that, as with the Maya, early writing was intricately involved with both royalty and the calendar.

For many archaeologists, the discovery, together with findings from new digs in even older Olmec sites, reinforces the notion that the Olmec was a “mother culture” and the primary influence on the later Maya and Aztec. “When the Olmec area was flourishing, there was nothing else like it,” says archaeologist Michael Coe of Yale University. “This is the place where everything was innovated.” The new glyphs add solid evidence to this long-standing theory, Olmec boosters say. “This is the oldest writing,” says archaeologist Richard Diehl of the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. “It's the mother and father of all later Mesoamerican writing systems.”

But other experts counter that the new artifacts are too fragmentary to resolve the enduring question of Olmec influence, or even how writing developed in Mesoamerica. Some question the fragments' age and whether they meet strict definitions of writing. Those who favor a model of “sister cultures,” in which the Olmec were just one of a network of interacting cultures that all contributed to the development of key innovations, remain unswayed. “We strongly reject Olmec ‘influence’ on the ancient cultures of central Mexico,” says archaeologist David Grove of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

The Olmec world

Several clues have long suggested that the Olmec were the first to develop

crucial aspects of Mayan culture, including writing. “The mother-culture

thesis is that the glories of the Maya are directly derivative of cultural

attainments of the earlier Olmec,” explains John Clark of Brigham

Young University in Provo, Utah. According to this view, the large-scale

Olmec architecture and monumental sculpture suggest that these people

were the first in Mesoamerica to concentrate broad political power in

the hands of a few. Linguistically, other Mesoamerican regions have

apparently borrowed words related to writing and the sacred calendar

from the precursor to the language now spoken in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec,

the Olmec heartland.

But hard evidence of Olmec scribes is scant. In the major Olmec city of La Venta in the Gulf Coast region of what is now southern Mexico, researchers have uncovered two monuments containing a linear sequence of glyphs. But their age is unclear. They could be anywhere from 600 B.C. to 400 B.C., so they don't settle the question of when and where writing began.

Then in 1997, Pohl and her co-authors—Kevin Pope of Geo Eco Arc Research in Aquasco, Maryland, and Christopher von Nagy of Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana—began to dig at a smaller site known as San Andrés, 5 kilometers from La Venta. They uncovered a stratified deposit of floors, hearths, and trash heaps (Science, 18 May 2001, p. 1370). The layers of refuse contained many sherds of pottery, plus some real showstoppers: a fist-sized cylinder seal and engraved chips of greenstone a bit smaller than a thumbnail. Radiocarbon dating allowed the researchers to come up with a date, 650 B.C., for the engraved objects—an “amazing” achievement, says Clark.

These artifacts have features that the researchers interpret as symbols indicating words. For example, the greenstone fragments bear two inscribed oval glyphs that might be part of a columnar text, as are later inscriptions from the region. Inscribed on the cylinder is a single glyph and a bird's beak spewing two diverging lines. Pohl says that in later inscriptions from outside the Olmec heartland, human mouths also emit lines, in symbols called speech scrolls. At the end of the bird's scroll are U-shapes, a common ingredient in later Mesoamerican writing.

The speech scroll indicates that the inscriptions on the cylinder are more than just representational art, say Pohl and others. “The implication is that they are representing words or sounds of a language,” says Martha Macri, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of California, Davis. The symbols are also not iconographic—they don't look like what they are supposed to mean—so they must be learned, Macri points out. “That's one of the hallmarks of writing,” she says.

The glyph on the cylinder is a U surrounded by an oval and next to three small circles. It resembles a Maya symbol with three dots called “3 Ajaw,” a date in the Mesoamerican calendar. “I think it's definitely the day sign ‘ajaw,’” says Coe, although others aren't so sure. If correct, this day sign coupled with a number are the first archaeological hints of the all-important 260-day Maya sacred calendar. And in Maya writing, ajaw means king as well as a date. Thus, Pohl reads the Olmec cylinder seal as the name “King 3 Ajaw,” which makes sense because Mesoamericans were often named for the day of their birth. The San Andrés seal could have been used to print a royal message, the team says.

But some researchers question the age and meaning of the fragments. Radiocarbon dates for this period always have wide margins of error; thus, by radiocarbon dating alone, the San Andrés glyphs may range from 792 B.C. to 409 B.C. Von Nagy, the team's ceramist, says that associated pottery fragments helped narrow the range to between 700 B.C. and 600 B.C. And although Pohl argues that a glyph that was “spoken” is evidence of writing, linguists and epigraphers tend to have a stricter definition. They want to see columns or rows of glyphs with word order and syntax—far more than these fragments can reveal. “A few isolated emblems … fall well below the standard for first writing,” says epigrapher Stephen Houston of Brigham Young University. “Show me a real text with sequent elements, and I'll be more convinced.”

All the same, many researchers agree that even if these fragments aren't full-fledged writing, they document steps toward it. Pohl suggests, for example, that formatted rows and columns came later. “It's at the cusp between iconography and writing,” agrees archaeologist Chris Poole of the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

The mother culture?

To Poole, all this fits with other emerging evidence that the Olmec

played “a special role … in the development and dissemination

of many cultural traits important for Mesoamerica.” New data are

making it clear that large populations and political structures developed

first in the Olmec, he and others say.

For example, over the past decade, Ann Cyphers of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, and her colleagues have discovered that the early Olmec center of San Lorenzo in Veracruz, active from 1200 B.C. to 900 B.C., is much more sophisticated than previously thought. The main site, replete with monumental sculptures of humans and felines, also featured an aqueduct that delivered spring water, plus a 100-square-meter “palace” with basalt drains. This might have been a seat of government, says archaeologist Kent Reilly of Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos. A survey of sites in the surrounding 800 square kilometers suggests that Olmec power extended far beyond the capital. For example, a site strategically located near the confluence of two rivers has thrones that are smaller than those at San Lorenzo but decorated in a similar fashion. “The way the settlement works on a regional level, we really think it was an incipient state,” says Cyphers.

Despite this apparent concentration of political power, opinions remain divided on the Olmec share of influence. Scholars who favor the “sister culture” view note that the Olmec borrowed pottery styles from elsewhere, and that there was a bustling trade in goods such as obsidian tools and jade ornaments throughout ancient Mesoamerica. Grove of the University of Florida agrees that many cultures were active. And the new writing fragments are not enough to change the views of these scholars. Even if the glyphs are ancient, Grove, for one, isn't convinced that the La Venta area was necessarily the first site of writing. “I don't think it shows the Olmec invented it. It could have originated anywhere around that southern region,” he says, especially because the seal and plaques were easy to transport.

There's also evidence that other Mesoamerican cultures were experimenting with writing, possibly at about the same time. Joyce Marcus and Kent Flannery of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, excavated a monument from San José Mogote, made by the Zapotec culture centered in Oaxaca, about 300 kilometers from La Venta. But although Marcus dates this monument at 600 B.C. to 500 B.C., Pohl and others are skeptical of that age. Archaeologist Javier Urcid of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, says the Zapotec monument contains a day-name glyph, which he considers writing. He thinks the greenstone plaques from San Andrés are writing too, and they might have been invented independently. “Even if writing did originate in a single spot, I don't think we'll ever be able to find it,” he says.

Whatever its origins, Mesoamerican writing flourished in the centuries after these early inscriptions began to appear. Even defeat did not stop the scribes, at least for long. Eleven years after the defeat of 18 Rabbit, for example, a new ruler of Copán tried to wipe away the bitter memory with a grand history of his city's warrior kings—the longest hieroglyphic text known from the New World.

~~~~~~~~

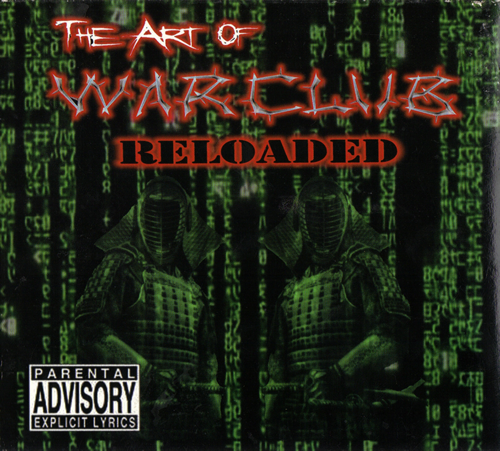

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06