Title: AZTECS: A NEW PERSPECTIVE , By: Pohl, John M. D., History Today,

00182753, Dec2002, Vol. 52, Issue 12

Database: Academic Search Elite

AZTECS: A NEW PERSPECTIVE

Contents

FOR FURTHER READING

John M.D. Pohl reviews recent scholarship about the empire swept away

by Cortes.

AS THE WARRIORS stand before the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán listening to speeches given by the emperor, they gaze out over the plaza looking for the faces of their proud families among the multitude who have come to witness their triumph. One mighty veteran gets a firmer grip on the hair of the prisoner kneeling at his feet and looks up at the towering pyramid to ponder the shrine of his patron god. It is the sworn duty of every Aztec soldier to carry on the legacy of Huitzilopochtli, Hummingbird of the South; to be ever vigilant, ever prepared to protect his family and his city from those who would destroy all that his ancestors had worked to accomplish.

The captive resigns himself to his fate; he knew the fortunes of war when he joined the army of his city-state in revolt against the empire. The priests approach and the warrior makes his presentation. Now is the time for the final conflict, the triumph, the conclusion of battle to be witnessed there in the central precinct by the Aztec people themselves. The captive will reenact the role of a cosmic enemy, living proof of Huitzilopochtli's omnipotence, of his power manifest in the abilities of the warriors, his spiritual descendants, to repay him for his blessings. The captive is pulled on to his back over the surface of a stone disk emblazoned with the image of the sun. He is held down by four priests, while a fifth drives a knife into his chest. The trauma of the blow kills him nearly instantaneously. Just as quickly the priest slits the arteries of the heart and lifts the bloody mass into the air, pronouncing it to be the 'precious eagle cactus fruit', a supreme offering to the solar god.

Every time I look upon the colossal monument known as the Aztec Calendar Stone, I try to imagine such rituals following Aztec military campaigns. Thousands of people participated -- to reassure themselves that their investment in supplying food, making weapons and equipment, and committing the lives of their children to the armies would grant them the benefits of conquest that their emperors guaranteed.

Aztec civilisation has been clouded in mystery and misunderstanding for centuries. For many people, knowledge of the Aztecs is confined to vague recollections of the illustrated books of youth and their graphic depictions of grisly sacrifices. This may be more true in Britain, indeed in Europe, than in North America where we have been privileged to witness a remarkable rediscovery of the Aztec culture over the past two decades. Aztec 'sacrifice', for example, once perceived as a ruthless practice committed by a 'tribe' seemingly obsessed with bloodshed, is now seen as no more or less brutal than what many imperial civilisations have done to 'bring home the war' in the words of my colleague, the Harvard professor, David Carrasco.

Today we witness war on television to confirm for ourselves that what a government claims they are doing in the interests of national security is worth the cost in resources and human life. But ancient societies had no comparable means to convey the image of battle to the heartland of their culture. Roman triumphs were a means of doing just this, and were more important than battlefields for ambitious politicians, and we should not forget that those captives who were forced to march in their thousands to celebrate the glorious commander were condemned to horrifying deaths in the Colosseum. The Aztec rituals were no different.

In their songs and stories the Aztecs described four great ages of the past, each destroyed by some catastrophe wrought by vengeful gods. The fifth and present world only came into being through the self-sacrifice of a hero who was transformed into the Sun. But the Sun refused to move across the sky. without a gift from humankind to equal his own. War was therefore waged to obtain the holy food that the Sun required, and thus to perpetuate life on Earth. The Aztecs used no term like 'human sacrifice' for their rituals. For them it was next-laualli, the sacred debt payment to the gods. Thus warfare, sacrifice and the promotion of agricultural fertility were inextricably linked in their religious ideology. Meanwhile for the Aztec soldiers, participation in these rituals was a means of displaying their prowess, gaining rewards from the emperor's own hand, and announcing their promotion in society. In addition, the executions served as a grim reminder for foreign dignitaries, lest they should ever consider making war against the empire themselves.

The very name 'Aztec' is debated by scholars today. The word is not really indigenous, though it does have a cultural basis. It was first proposed by a European, the explorer-naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), and later popularized by William H. Prescott in his remarkable 1843 publication The History of the Conquest of Mexico. 'Aztec' is an eponym derived from Aztlan, or 'Place of the White Heron', a legendary homeland of seven desert tribes called Chichimecs who miraculously emerged from caves located at the heart of a sacred mountain far to the north of the Valley of Mexico. The Chichimecs enjoyed a peaceful existence, hunting and fishing, until they were divinely inspired to fulfil a destiny of conquest y their gods. They journeyed until one day they witnessed a tree being ripped asunder by a bolt of lightning. The seventh and last tribe, known as the Mexica, took the event as a sign that they were to divide and follow their own destiny. They continued to wander for many more years, sometimes hunting and sometimes settling down to farm, but never remaining in any one place for long. When Tula, the capital of a powerful Toltec state that had dominated central Mexico for four hundred years, collapsed, the Mexica decided to move south to Lake Texcoco.

Impoverished and without allies, the Mexica were subjected to attacks by local Toltec warlords who forced them to retreat to an island where they witnessed a miraculous vision of prophecy: an eagle standing on a cactus growing from solid rock. It was the sign for Tenochtitlán, their final destination. Having little to offer other than their reputation as warriors, the Mexica hired themselves out as mercenaries to rival Toltec factions. Eventually they were able to affect the balance of power in the region to such a degree that they were granted royal marriages. Now the most powerful of the seven original Aztec tribes, by the early fifteenth century the Mexica incorporated their former enemies and together they built an empire. Eventually they were to give their name to the nation of Mexico, while their city of Tenochtitlán became what we know as Mexico City. The term Aztec is applied to the archaeological culture that dominated the Basin of Mexico in the fifteenth and early sixteenth century, but the people themselves were ethnically highly diverse.

Tenochtitlán was officially said to have been founded in 1325 but it was over a century before the city rose to its height as an imperial capital. Between 1372 and 1428, the Mexica emperors -- called huey tlatoque or 'great speakers' -- Acamapichtli (r. 1376-96), Huitzilihuitl (r. 1397-1417), and Chimalpopoca (r. 1417-27) served as the vassals of a despotic Tepanec lord named Tezozomoc of Azcapotzalco. They shared in the spoils of victory and succeeded in expanding their own domain south and east along Lake Texcoco. But when Tezozomoc died in 1427, his son Maxtla seized power and had Chimalpopoca assassinated. The Mexica quickly appointed Chimalpopoca's uncle, a war captain named Itzcóatl, as emperor. Itzcóatl allied himself to Nezhualcoyotl, deposed heir to the throne of Texcoco, the kingdom lying on the eastern shore of the lake. Together the two kings attacked Azcapotzalco. The siege lasted for over a hundred days and only concluded when Maxtla relinquished his throne and retreated into exile. Itzcóatl and Nezhualcoyotl then rewarded the Tepanec lords who had aided them, and the three cities of Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan formed the new Aztec Empire of the Triple Alliance.

Itzcóatl died in 1440 and was succeeded by his nephew Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina. Motecuhzoma I (r. 1440-69), as he was later known, charted the course for Aztec expansionism for the remainder of the fifteenth century and was succeeded by his son Axayacatl in 1469. Axayacatl had proven himself a capable military commander as a prince, now he sought to capitalise on the conquests of his father by entirely surrounding the kingdom of Tlaxcala to the east and expanding imperial control over the Mixtecs and Zapotecs of Oaxaca to the south. But by 1481, Axayacatl had died. He was followed by Tizoc, who ruled briefly but ineffectually. In 1486, the throne passed to Tizoc's younger brother, Ahuitzotl (r. 1486-1502), who proved himself an outstanding military commander. Ahuitzotl reorganised the army and soon regained much of the territory lost under the previous administration. He then initiated a programme of long-distance campaigning on an unprecedented scale. The empire reached its apogee under Ahuitzotl, dominating possibly as many as 25 million people throughout the Mexican highlands. Ahuitzotl was succeeded by the doomed Motecuhzoma II (r. 1502-20) who suffered the catastrophic Spanish invasion under Hernan Cortés.

The land mass of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital founded on a small island off the western shore of Lake Texcoco, was artificially expanded until eventually it covered more than five square miles. The city was divided into four districts. Each district was composed of neighbourhood wards of landowning families called calpulli, or 'house groups'. Most of the calpulli were inhabited by farmers who cultivated bountiful crops of corn, beans, and squash using an ingenious system of raised fields called chinampas, while others were occupied by craftspeople. Six major canals ran through the metropolis, with many smaller ones criss-crossing the entire city, making it possible to travel virtually anywhere by boat. Boats were also the principal means of transportation to the island. Scholars estimate that between 200,000 and 250,000 people lived in Tenochtitlán in 1500, more than four times the population of London at that time.

There were three great causeways that ran from the mainland into the city. These were spanned with drawbridges that, when taken up, sealed the city off entirely. Fresh water was transported by a system of aqueducts, of which the main construction ran from a spring on a mountain called Chapultepec to the west. The four districts each had temples dedicated to the principal gods, though these were overshadowed by the Great Temple, a man-made mountain constructed within the central precinct and topped by dual shrines dedicated to the Toltec storm god Tlaloc and the Chichimec war god Huitzilopochtli. The surrounding precinct itself was a city within a city of over 1,200 square metres of temples, public buildings, palaces, and plazas enclosed by a defensive bastion called the coatepantli or serpent wall, so named after the scores of carved stone snake heads that ornamented its exterior.

In November 1519, the band of 250 Spanish adventurers stood above Lake Texcoco and gazed upon Tenochtitlán. The Spaniards were dumbfounded and many wondered if what they were looking at was an illusion. The more worldly among them, veterans of Italian wars, compared the city to Venice but were no less astonished to find such a metropolis on the other side of the world. At the invitation of the Emperor Motecuhzoma, Hernan Cortés led his men across the great Tlalpan causeway into Tenochtitlán. He later described what he saw in letters to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Cortés marvelled at the broad boulevards and canals, the temples dedicated to countless gods, as well as the magnificent residences of the lords and priests who resided with the emperor and attended his court. The Spaniard described the central market where thousands of people sold everything from gold, silver, gems, shells and feathers, to unhewn stone, adobe bricks, and timber. Each street was devoted to a special commodity, from clay pottery to dyed textiles, while a special court of judges enforced strict rules of transaction. All manner of foods were bartered: dogs, rabbits, deer, turkeys, quail and every sort of vegetable and fruit.

What happened once Cortés had entered the city is a long-familiar tale, retold from vivid reports of the Europeans themselves: though the Spaniards were initially. welcomed, they seized emperor Motecuhzoma, held him hostage and forced him to swear allegiance to the king of Spain. In June 1520 Motecuhzoma was killed while trying to placate his subjects. Cortés was forced to retreat, but came back to beseige Tenochtitlan, which fell after three months in August 1521.

Some of the most dramatic recent changes to our perception of the Aztecs have come with a critical reappraisal of the histories of the Conquest itself. Spanish accounts traditionally portrayed the defeat of the Aztec empire as a brilliant military achievement, with Cortés' troops, outnumbered but better armed with guns and cavalry, defeating hordes of superstitious savages. The reality now appears far more complex. During the first year-and-a-half of the conflict, the Spaniards rarely numbered over 300 and frequently they campaigned with fewer than 150. Their steel weapons may have had an impact initially, but they soon ran out of gunpowder and by 1520 had eaten their remaining horses. So what accounted for their incredible achievement? They owed their success not so much to superior arms, training, and leadership as to Aztec political factionalism and disease.

With his publication in 1993 of Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico, Hugh Thomas exploded the myths of the Conquest, demonstrating that in nearly all their battles, the Spaniards were fighting with Indian allied armies that numbered in the tens of thousands. Initially these were drawn from disaffected states to the east and west of the Basin of Mexico, especially Tlaxcala, but by 1521 even the Acolhua of Texcoco, cofounders of the empire together with the Mexica, had appointed a new government that clearly saw an opportunity in the defeat of their former allies. The extent to which the Spaniards were conscious of strategy in coalition-building or whether they were actually being manipulated by Indians themselves is unknown. But on August 13th, 1521, when Cortés defeated Tenochtitlán, he was at the head of an allied Indian army estimated by some historians at between 150,000 and 200,000 men. Yet even this victory was only achieved after what is considered to be the longest continuous battle ever waged in the annals of military history.

By now, successive epidemics of smallpox and typhus -- diseases unknown in Mexico prior to the arrival of the Europeans -- were raging. Neither the Europeans nor the Indians appreciated that disease could be caused by contagious viruses. In fact successive epidemics would take away first 25, 50, and eventually 75 per cent of the population of an entire city-state within a year. By the summer of 1521, smallpox in particular had created a situation that allowed Cortés to assume the role of a kind of 'kingmaker,' appointing new governments among his allies, as the leaders of the old regimes loyal to the Mexica succumbed to sickness.

The Pre-Columbian city was totally destroyed during the siege of 1521 and the Spanish colonialists founded their own capital, Mexico City, on the ruins. After this, knowledge of Tenochtitlán's central religious precinct remained largely conjectural. The traditional belief that the Great Temple might lie beneath Mexico City's contemporary zocalo or city centre seemed to be confirmed in 1790, with the discovery of the monolithic sculptures known as the Calendar Stone and the statue of Coatlique, the legendary mother of Huitzilopochtli. Writings, drawings, and maps from the early colonial period appeared to indicate that the base of the Great Temple had been approximately 300ft square, with four or five stepped levels rising as high as 180ft. There were descriptions of dual staircases on the west side, stopping before two shrines at the summit. Only recently, however, has systematic archaeological excavation provided a more certain idea of what the Spanish invaders actually witnessed.

On February 21st, 1978, Mexico City electrical workers were excavating a trench, six feet below street level to the northeast of the cathedral, when they encountered a monolithic carved stone block. Archaeologists were called to the scene to salvage what turned out to be a stone disk carved with a relief in human form, eleven feet in diameter. The image was identified as a goddess known as Coyolxauhqui, 'She Who is Adorned with Bells'. According to a legend recorded by the Spanish friar and ethnographer Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590), there once lived an old woman named Coatlicue or Lady Serpent Skirt, together with her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, and her 400 sons at Coatepec, meaning Snake Mountain. One day as Coatlicue was attending to her chores she gathered up a mysterious ball of feathers and placed them in the sash of her belt. Miraculously, she found herself with child. But when her daughter Coyoxauhqui saw what had happened she was enraged and shrieked: 'My brothers, she has dishonoured us! Who is the cause of what is in her womb? We must kill this wicked one who is with child!'

Coatlicue was frightened but Huitzilopochtli, who was in her womb, called to her saying: 'Have no fear mother, for I know what to do.' The 400 sons went forth. Each wielded his weapon and Coyolxauqui led them. At last they scaled the heights of Coatepec. At this point there are many variations to the story but it appears that when Coyolxauhqui and her brothers reached the summit of Coatepec they immediately killed Coatlique. Then Huitzilopochtli was born in full array with his shield and spear thrower. At once he pierced Coyolxauhqui with a spear and then he struck off her head. Her body twisted and turned as it fell to the ground below the Snake Mountain. Then Huitzilopochtli took on the 400 brothers in equal measure and slew each of them.

Examination of the Coyolxauhqui stone led the National Institute's director of excavations, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, to conclude that the monument had never been seen by the Spaniards, much less smashed and reburied like so many other Aztec carvings. Remembering that Coyoxauhqui's body was said to have come to rest at the foot of the mountain, the archaeologists began to surmise that Coatepec, or rather its incarnation as the Great Temple, might lie very nearby. It was not long before they discovered parts of a grand staircase and then the massive stone serpent heads, literally signifying the Snake Mountain Coatepec, surrounding the base of the pyramid itself. The Great Temple had been found by decoding a thousand-year-old legend.

Since 1980 the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History has carried out almost continuous excavations, uncovering at least six separate building phases of the Great Temple, as well as numerous smaller temples and palaces from the surrounding precinct. Excavations carried out by Leonardo Lopéz Luján and his associates have uncovered no fewer than 120 caches of priceless objects buried as offerings from vassal states within the matrix of the Great Temple. Further excavations, even tunnelling under the streets of Mexico City, to the north of the site have revealed an astounding new structure called the House of the Eagles (named for the stone and ceramic statuary portraying the heraldic raptor), which has yielded even greater treasures. Perhaps the most dramatic finds are frightening life-size images of Mictlantecuhtli, god of the underworld. Lopéz and his associates, examining images of Mictlantecuhtli found in pictographic books called codices, noted that they are depicted being drenched in offerings of blood. New techniques to identify microscopic traces of organic material were applied to the spot where the statues were found, that revealed extremely high concentrations of albumin and other substances pertaining to blood on the floors surrounding pedestals on which the statues once stood, a testament to the veracity of the ancient Aztec books.

One of the most remarkable discoveries was a stone box that had been hermetically sealed with a layer of plaster. Inside lay the remains of an entire wardrobe, headdress, and mask for a priest of the Temple of Tlaloc, the ancient Toltec god of rain and fertility whose shrine stood next to that of Huitzilopochtli at the summit of the pyramid. Despite the lavish depictions of Aztec ritual clothing in the codices, none was known to have survived the fires of Spanish evangelistic fervour. For the first time we have a glimpse of the perishable artefacts which played such a major role in Aztec rituals, pomp and ceremony.

During the course of excavations within the matrix-fill of the Great Temple, archaeologists have found the remains of objects very much like those well-known from earlier collections, together with hordes of other exotic materials. Investigators were initially puzzled by the discovery of hordes of shells, jade beads, greenstone masks, jaguar and crocodile bones, exquisitely painted vessels, textile fragments and quantities of other exotic materials. The clue lay in the Codex Mendoza, an pictographic book of Aztec civilisation compiled under Spanish supervision in 1541 and preserved in Oxford University's Bodleian Library. Here, the manuscript inventories the entire tribute of the empire for one year. Hieroglyphic place-signs name cities and provinces conquered throughout the fifteenth century. Pictographs for staple foods such as maize, beans, and squash appear, but the great majority of the pictographs represent precisely the same kinds of exotic goods found in the excavations.

Many ancient societies buried precious materials, including works of art. Economists argue that such practices served as levelling mechanisms when the supply of anything rare or labour intensive exceeded demand. The Aztecs compared war to a market place and it appears that there was more to this than just metaphor.

In societies like the Mixtecs and Zapotecs of southern Mexico, with whom the Aztecs fought nearly continuously for seventy-five years, the production and consumption of luxury goods in precious metals, gems, shell, feathers, and cotton was restricted to the elite. Commoners were even forbidden to wear jewellery. Royal women were the principal craft producers and the kings sought to marry many wives, not only to forge alliances but so that they could enrich themselves by exchanging the women's artistic creations through dowry, and other gift-giving networks. A king might marry as many as twenty times, so each palace could produce luxury goods to be measured by the ton. By 1200 CE, royal palaces throughout the central and southern highlands of Mexico began to engage in fiercely competitive reciprocity systems to enhance their positions within alliance networks. The greater the ability of a royal house to acquire exotic materials and to craft them into exquisite jewels, textiles, and featherwork, the better marriages it could negotiate. The better marriages it could negotiate, the higher the rank a royal house could achieve within a confederacy and, in turn, the better access it would have to materials, merchants, and craftspeople. In short, royal marriages promoted syndicates.

Historians are beginning to recognise that the Aztec strategy of military conquest was not only to secure supplies of food. It also sought to subvert the luxury economies of foreign states, forcing them to produce goods for the Empire's own system of gift exchange: rewards for military valour that made the soldiers of the imperial armies dependent upon the emperor himself for promotion in Aztec society. The outlandish uniforms seen on the battlefield must also have served as graphic proof of the kind of crushing tribute demands the Aztec empire could inflict. No less than 50,000 woven cloaks a month were sent by the conquered provinces to Tenochtitlán. For the kingdoms of southern Mexico, the prospect of being forced to subvert their artistic skills to the production of military uniforms to be redistributed to an ever more glory-hungry army of Aztec lords and commoners alike must have been a frightening proposition.

A great many Aztec artefacts were taken back to Europe by the Spanish; finely wrought jewels of gold, human skulls studded with turquoise mosaic, heraldic shields ornamented with the feathers of rare tropical birds, and dazzling codices all mesmerized the court of Habsburg Spain. Later these became highly prized by the nobility of Europe, in some cases passing between princes as ambassadorial presents. Others were seized as war booty and fell into the hands of collectors who valued them but were often at a loss to understand what they were or who had created them. It was only when a new generation of scholars and adventurers began to explore the ruins of Mexico and Central America in the nineteenth century that their meaning began to be appreciated. In November of this year, a major exhibition at the Royal Academy in London will be the first time that these have been brought together with the stunning finds of the past twenty-five years from the Great Temple site.

FOR FURTHER READING

Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt, Codex Mendoza. Four Volumes.

(University of California Press, 1992); Elizabeth Hill Boone, The Aztec

World (St Remy Press, Washington 1994); David Carrasco and Eduardo Matos

Moctezuma, Moctezuma's Mexico: Visions of the Aztec World (University

of Colorado Press, 1992); Diego Durán, The History of the Natives

of New Spain. Translated, annotated, and with an introduction by Doris

Heyden. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1994); Eduardo Matos Moctezuma,

The Great Temple of the Aztecs: Treasures of Tenochtitlán (Thames

and Hudson, 1988); Esther Pasztory, Aztec Art (Harry N. Abrams Inc,

1983); John M.D. Pohl, The Aztec Warrior (Osprey, 2001); Michael E.

Smith, The Aztecs (Blackwell, 1994); Richard Townsend, The Aztecs (Thames

and Hudson, 1992).

MAP: Gulf of Mexico

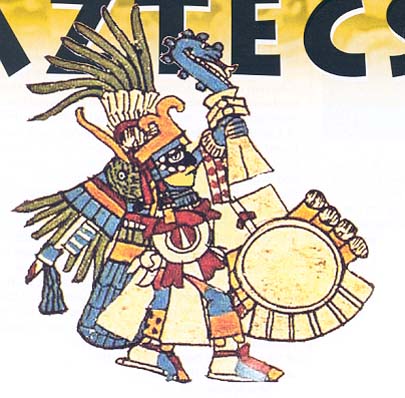

Huitzilopochtli, the war god of the Aztecs, illustrated in a Spanish-period

manuscript.

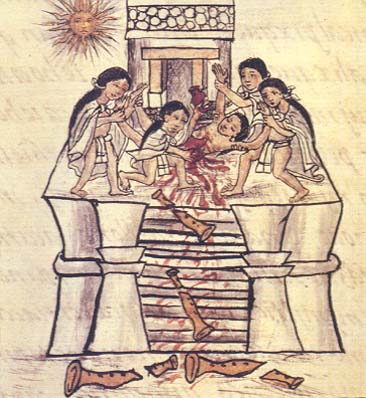

A captive's heart is cut out and offered to the god Tezcatlipoca, patron

of the Aztec rulers.

A sacrificial flint knife with turquoise mosaic handle.

The 3.6m diameter Calendar Stone, found in the main square of Mexico

City in 1760, was placed horizontally on a platform before the Great

Temple and served as a cuauhxicalli (eagle vessel) for the sacrifice

of enemy warriors. The central image depicts the sun god of the fifth

or present age of the Mexica cosmos encircled by fire serpents.

According to the Aztec foundation myth, the tribes left their island

homeland of Aztlan in c. CE 1000; the god Huitzilopochtli then spoke

to them in a cave. From the Codex Boturini.

A modern evocation of Tenochtitlán, the island capital connected

to the mainland by three causeways. The view is from the west.

A Spanish Colonial Painting of the decisive battle in which Cuauhtemoc,

briefly emperor after the death of Motecuhzoma, was captured.

A high-ranking captive defends himself with mock weapons against a heavily

armed Mexica Jaguar warrior in gladiatorial combat before the Temple

of Huitzilopochtli.

An Aztec shield sent to Europe shortly after the Conquest depicts a

coyote in intricately worked feathers of tropical birds.

A colossal statue depicts the decapitated mother of Huitzilopochtli,

Coatlicue. The dual snake heads signify blood gushing from the wound.

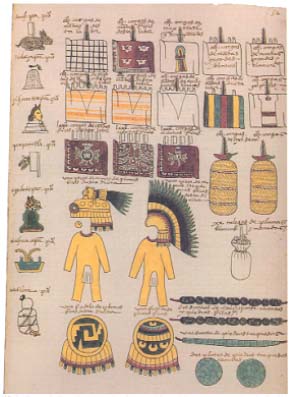

The Codex Mendoza portrays lists of city-states conquered by the Aztec

empire. Tribute was paid in staple commodities, in this case bundles

of chili peppers. Exotic materials are also demanded, like woven capes,

turquoise inlaid disks, strings of green stones, and elaborate warrior

outfits covered in feathers.

The Templo Mayor, in the heart of Mexico City, has been the focus of

nearly twenty-five years of excavation. The remains of other temples

and palaces still lie beneath Mexico City's main square.

Standing stone figures excavated on the staircase of the Great Temple

represent the earliest forms of an Aztec sculptural tradition.

The Coyolxauhqui Stone was carved from a Fine grained volcanic matrix.

It depicts the goddess lying on her side, having been cast down from

Coatepec or Serpent Mountain by her brother Huitzilopochtli. She was

subsequently commemorated as a lunar goddess.

Detail of an elaborate Aztec headdress composed of shimmering green

quetzal bird feathers and miniature shields of gold.

~~~~~~~~

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06