Natural History, April 2001 v110 i3 p66

Other Stars Than Ours. Anthony F. Aveni.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2001 American Museum of Natural History

Aztec astronomers had their own reasons for sky watching.

The Aztecs saw in the heavens the sustainers of life--the gods they sought to repay, with the blood of sacrifice, for bringing favorable rains, for keeping the earth from quaking, for spurring them on in battle. Among the gods was Black Tezcatlipoca, who ruled the night from his abode in the north, with its wheel (the Big Dipper). He presided over the cosmic ball court (Gemini) where the gods played a game to set the fate of humankind. He lit the fire sticks (Orion's belt) that brought warmth to the hearth. And at the end of every fifty-two-year calendrical cycle, Black Tezcatlipoca timed the rattlesnake's tail (the Pleiades) so that it passed overhead at midnight--a guarantee that the world would not come to an end but that humanity would be granted another epoch of life. The priests in Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, climbed to the top of their sky watchers' temple on the Hill of the Star to witness this auspicious sign. The Aztecs lived their sky, knowing that everything that happened on earth was the outcome of destiny. And they wrote it all down in their books.

Created in the late fifteenth century, the Codex Borgia, a seventy-six-page "screenfold" document of deerskin, is one of a handful of Aztec manuscripts that escaped the Spaniards' book burnings. "Paganism must be torn up by the roots from the hearts of these frail people!" wrote the Dominican friar Diego Duran, a sixteenth-century chronicler horrified by such documents, which often included graphic depictions of sacrifice and dismemberment. And in fact, some pages in the Codex Borgia do have illustrations of stabbing and blinding and of blood squirting from a torso with dangling intestines. But this random survivor from Mexico's past is also a mine of impressive information about Aztec astronomy.

Much of the first half of the codex prescribes the performance of "debt payment" rituals, as the sixteenth-century Franciscan priest Bernardino de Sahagun put it. These rituals were to be carried out with reference to a sacred calendar called the tonalpohualli, the "count of days." This round of time operated much like the Western calendar's cycling of seven named weekdays in tandem with each month's numbered days (Monday the 1st, Tuesday the 2nd, and so on), except that it cycled twenty signs (representing various animals, plants, and forces of nature) against thirteen numbers. This yielded a sequence of 260 uniquely named days (1 Crocodile, 2 Wind, 3 House, and so on), after which the sequence would begin again. The rest of the Codex Borgia is a pictorial narrative detailing the attributes of supernatural characters--probably patron gods of the ruling Aztec lineage for which the codex was prepared--and the world they inhabited prior to humanity's existence.

Recently I have been delving into certain pages in this little-understood codex--pages that resemble Mayan almanacs, which are well known for their precise prediction of astronomical events. My working hypothesis has been that the dates designated in the Codex Borgia for the performance of rituals were chosen by Aztec prognosticators, who calculated when the heavenly bodies would be in especially auspicious or dangerous positions. If we take just one page in the codex--page 28--as an example, we can begin to see how they put their astronomical expertise to use.

This page (reproduced at the opening of this article) depicts five similar figures, one for each of the cardinal directions (most likely starting with east at the lower right and running counterclockwise to north, west, and south), along with a central one representing the up-down axis, a standard dimension in Mesoamerican cosmology. The featured player is Tlaloc, the goggle-eyed, long-fanged god of rain and fertility, who appears at the top of each frame in a similar pose but with varied accoutrements. At lower right, for example, the rain he unleashes from each hand is studded with flint knives (hail); at upper right, it carries flowers; at lower left, it is accompanied by wind in the form of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent. Absorbing the seasonal punishments and rewards doled out by the forces of nature is the maize crop. In each frame, the maize is personified as an aged female deity, who is shown in a field beneath Tlaloc, flanked by plants bearing ears of corn.

Tlaloc may be the star of the show in another way, because he has a link with Venus. A variety of recent studies of both Mayan and Aztec sculpture, carved .inscriptions, and architecture have led to the discovery of a cult known to scholars as the Tlaloc-Venus-War complex, so called because of the imagery worn by its practitioners and the timing of its rites to coincide with particular stations of the planet Venus.

One of the brightest objects in the night sky, Venus commanded the attention of ancient sky watchers, just as it does today. Part of its fascination is that it periodically shifts from appearing as an evening star that sets shortly after sunset to appearing as a morning star that rises just before dawn. Between these manifestations, it disappears from the night sky altogether. All this is a consequence of the fact that the planet's orbit is closer to the Sun than ours is, so that from our point of view Venus seems to move back and forth across the Sun's position. (The reason we sometimes can't see Venus is that it gets so "close" to the Sun that it is lost in the daylight.)

Venus completes its entire appearing-disappearing-reappearing-disappearing act every 583.92 days. Coincidentally, Venus runs through five such cycles in the course of almost exactly eight solar years (a solar year is 365.2422 days). As a consequence, whatever we see Venus doing in the sky on a given date in our calendar, we can expect to see the planet do again, eight years later, on exactly or almost exactly the same day of the same month. For example, Venus begins to appear as a morning star around April 1, 2001, and around April 1, 2009, it will put on a repeat performance. The Aztecs, who had a 365-day calendar by which they measured the solar year, were well aware of this mathematical meshing, which added to Venus's attraction as an astronomical phenomenon.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the visionary German scholar Eduard Seler, who drew on his knowledge of Babylonian astronomical texts, suggested that page 28 in the Codex Borgia may have referred to events in the Venus cycle. He declared himself unable, however, "to discover a law for the days." He was referring to the dates, some of them effaced, that were written along the base of each of the five framed Tlalocs. Fortunately, not only has decipherment of these symbols improved since Seler's time, but high-speed computers now enable us to easily calculate the astronomical events to which ancient dates may correspond.

Within each frame, two tonalpohualli (ritual calendar) days are specified, as well as a third day that identifies the particular 365-day year in which the two days fall. Inconveniently for us, however, central Mexican calendars provided no long-term running count for the years, as their Classic Mayan counterparts did. Instead they tell us only the sign and number for the 360th day of the year they are referring to. (It's as if we identified 2001 only as "the year Tuesday-the-25th" because in 2001, Christmas falls on a Tuesday.) But this shorthand presented no problem to the Aztecs, since the same tonalpohualli day did not coincide again with the 360th day of the year for a long while.

Indeed, exactly how long did it take for a year name to be repeated? One might guess 260 years, since there are that many distinct days in the tonalpohualli cycle, with its twenty day signs and thirteen numbers. But when the twenty day signs are rotated in order against 365-day solar years, only four signs happen to fall on the 360th day--Reed, Flint, House, and Rabbit, after which we come back to Reed. These four, cycled against the thirteen numbers, provide fifty-two unique names for years. Thus the year name in which a person was born would not recur before he or she reached the age of fifty-two.

In each frame on page 28 of the codex, one of the day names serves to refer to the year. We can distinguish it because the day sign is superimposed over a sort of trapezoidal symbol, which essentially translates as "this is the year." Deciphering the year names on this page, we get the following: upper right, 2 Flint; upper left, 3 House; center, 5 Reed. Although the year names for the bottom two Tlaloc figures are partly effaced, it's a good guess that we're dealing with a sequence of five consecutive years, beginning at the lower right panel, continuing counterclockwise, and ending at the center: 1 Reed, 2 Flint, 3 House, 4 Rabbit, 5 Reed.

Next we have to determine when this five-year sequence falls with respect to our own calendar. From its style alone, we can date the Codex Borgia to sometime between the mid-fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Thanks to documents concerning the Spaniards' siege of Tenochtitlan, we know that April 8, 1519, was the first day of an Aztec year and that the name of the year was 1 Reed. This matches the first year in our sequence, so conceivably we are looking at a five-year sequence that ran from April 1519 to April 1524. Or we could drop back one cycle, to March 26, 1467, when 1 Reed also gave its name to a year. Given the approximate dating based on the codex's style, we don't have to look any earlier or later than these two possibilities.

Taking the years and the day names provided for each year, we can identify specific corresponding dates in the Western calendar. Now comes the fun part: testing whether the creators of page 28 intended its colorful scenes to be connected with specific, observable celestial events. Checking for any significant astronomical events that would have fallen on or near the dates in question, I found that the earlier sequence (from late March 1467 to late March 1472) yielded the most candidates. Many of its celestial-events involve Venus in some way, such as the planet's first appearance as an evening star or its alignment with other planets visible to the naked eye. Still, not every date provides a perfect match. Those that don't may have referred to celestial observations that the Aztecs deemed more important than we do and that may become apparent to us once we learn more. The Aztecs may even have sought to predict certain meteorological or geological phenomena--earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hailstorms, or the rare snowfall--that we do not include in the category of astronomical event.

Page 28 of the Codex Borgia is, in effect, one page in an almanac produced by astronomer-calculators to suit a particular time and place of celestial observation. (The adjoining page 27 seems to be a master plan that embraces larger segments of time, suggesting that the almanac as a whole may cover a full fifty-two-year period, from 1467 to 1519.) Each of the dates on page 28 was apparently considered a prime time to schedule a suitable propitiation ritual to Tlaloc, the deity that dominates the images. An important purpose of such rituals seems to have been to bring on needed seasonal rains or to ward off calamities that could befall the maize crop. Four of the dates cluster around mid-May, when the rains begin, a crucial time in the agricultural cycle.

Given the connectedness, for the Aztecs, of fertility, warfare, and Venus, the meaning of this page may run much deeper. The rain-drought cycle in the biosphere, the cycle of kingship in the human sphere, and the periodic motions in the celestial sphere all undergo similar junctures: just as new maize germinates, so does the empire flourish in the presence of the newly "sprouted" ruler, whose conquest and acquisition of tributary states are sanctioned in heaven by the wandering of his patron star. These interconnections aren't really that exotic. We should not forget that Western astronomy before the Enlightenment was also driven largely by astrological and religious concerns (even the major Christian holidays were pegged to observable celestial events). Louis XIV proclaimed himself Sun King; more recently, an astrologer was thought to have played a role in Ronald Reagan's conduct of presidential affairs.

While the Maya have long been credited with prowess in calendrical and astronomical matters, we are now seeing that the upstart Aztecs were also sophisticated in these realms. In fact, it appears that Mesoamerican cultures were much more interrelated than we once thought. The connections extended to their pantheons of gods, with those of the Maya and the Aztecs, like those of the Greeks and Romans, displaying many correspondences.

But perhaps the most important lesson we can derive from the study of Aztec astronomy is that these people simply were not concerned with what seems important to us now. Even the eclipses of the Sun they chose for temporal markers had to fall on special days of the tonalpohualli; whether or not these eclipses were spectacular by our criteria mattered less. But these astronomers were precise. For example, if we look at the early- to mid-sixteenth-century manuscript known as the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, we find that an eclipse that took place on the afternoon of August 8, 1496, is depicted just about as it happened, with the still partially eclipsed solar disk plunging into the mountainous horizon west of Tenochtitlan.

Caught up in the theory of progress, we tend to focus on whatever glimmers of modern science we find in ancient or, indigenous ways of understanding nature. We see that a certain group discovered an herb containing a curative chemical or recorded the position of the rising Sun at the vernal equinox. And then we lament, Just think what they might have accomplished if they had taken the "right track" and pursued this knowledge more single-mindedly. But we would do better to study how and why these cultures built elegant systems for making the things they observed comprehensible--not to us but to themselves. Other peoples' motives for sky watching may tax our patience and require dredging up subjects that suit neither our tastes nor our prejudices. But our failure to understand these motives will always be our loss.

Originally trained as an astronomer, Anthony

F. Aveni ("Other Stars Than Ours" page 66) was attracted to

indigenous New World calendars thirty years ago, when he took a group

of undergraduates to Mexico to see the Mesoamerican pyramids. An early

result of that interest was his book Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico (University

of Texas Press, 1980), which helped establish the field of archaeoastronomy--the

study of the astronomical practices, celestial lore, and cosmologies

of ancient cultures. A revised and updated edition of this classic will

be published later this year. Among the other books Aveni has authored

is Between the Lines: The Mystery of the Giant Ground Drawings of Ancient

Nasca, Peru (University of Texas Press, 2000). Honored in 1982 as U.S.

Professor of the Year by the Council for Advancement and Support of

Education, Aveni is the Russell B. Colgate Professor of Astronomy and

Anthropology at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York.

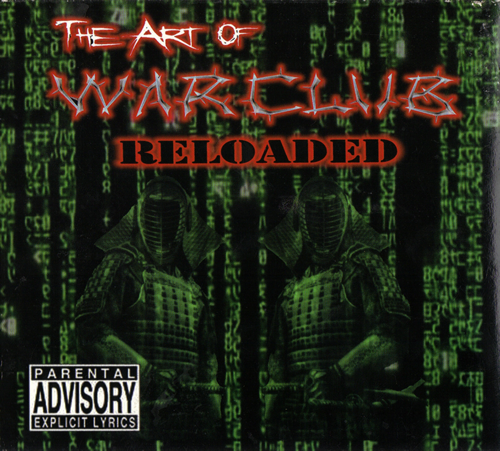

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06