Natural History, Dec 1999 v108 i10 p54

AZ-TECH MEDICINE. (manuscript details Aztec medicinal practice) ROB NICHOLSON.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1999 American Museum of Natural History

The History of Medicine in Mexico:

The People's Demand for Better Health, an 860-square-foot fresco by

the

great Diego Rivera, adorns a dim, quiet lobby in the Centro Medico La

Raza, a complex of modern hospitals in

the heart of Mexico City. Doctors pass it without a glance, even though

their heritage is spread before them in an

explosion of emotion, color, and form. On the left side of the painting,

Rivera depicted the health-care technology

of the 1950s--transfusions, vaccinations, X rays, hospital births, and

radiation therapy. To the right he showed the

practices of the Aztecs, Mexico City's pre-Columbian inhabitants. A

worried noble points at his heart while a

stern curandero hands him an infusion from the bloom of yolloxochitl,

a member of the magnolia family. A midwife

and her team bring forth an infant; other healers administer massage,

herbal poultices, dental care, medicinal

steambaths, and enemas. Trepanation, a primitive cranial operation used

by the Aztecs, is also illustrated, attesting

both to Rivera's scholarship and to the use of analgesics (could any

patient have borne the excruciating pain

without them?).

At the center of the mural, faithfully

copying an image from the early-sixteenth-century Codex Borbonicus,

Rivera

painted the Aztec goddess Tlalzolteotl, who was connected with cleansing

and fertility. Below her the artist paid

homage to another codex (manuscript book), the Badianus Manuscript,

by reproducing the majority of its

illustrations. Created in 1552, this repository of traditional medicinal

knowledge is the legacy of an Aztec artist

who labored at a Catholic mission that is now a mere two subway stops

from the Centro Medico. Two other

compendiums of Aztecana that include medical lore survive from about

the same period, one compiled by

historian and missionary Bernardino de Sahagun and the other by court

physician Fernando Hernandez. These

two texts cover a greater number of plant species than the Badianus

does, and in the case of Hernandez's work,

one could say that the ink drawings are more accurate botanically. But

of the three, the Badianus is the oldest,

and its renderings are essentially the earliest surviving illustrations

of New World plants. Having seen the amazing

floral wealth of Mexico on numerous collecting expeditions, I favor

the Badianus Manuscript for the kick I get out

of recognizing species of plants I have come upon during fieldwork and

for the visual joy I derive from the utterly

flamboyant colors--as bright as a Mexican cottage garden in full sun.

From 1519 through the 1520s, the

Spanish conquistadores and the priests and administrators who followed

them

did their best to tear down the Aztec monarchy and impose Christianity.

In the process, much of Aztec

heritage--the accumulated wisdom as well as the artifacts and architecture--was

lost or destroyed, including most

Aztec works on bark paper. Almost immediately, however, efforts got

under way to salvage and record

traditional knowledge, including indigenous medications. In 1545, for

example, Spanish physician Nicolas

Monardes published an (unillustrated) account of botanical cures, a

version of which was also translated into

English under the title Ioyfull Newes out of the Newe Founde Worlde,

Wherein Is Declared the Rare and

Singuler Vertues of Diuerse and Sundrie Hearbes, Trees, Oyles, Plantes,

and Stones, with Their Applications, as

Well for Phisicke as Chirurgerie. Plants such as sassafras, tobacco,

coca, and "holie woodde" were touted as

potent new remedies (the last refers to species of Guaiacum, or lignum

vitae, used to treat venereal disease).

At what had been the great marketplace

of Tenochtitian (the Aztec capital that became Mexico City), the

Franciscan order erected a church and convent known as Santiago de Tlaltelolco.

There, in 1536, Viceroy

Antonio de Mendoza established the College of Santa Cruz, one of the

first European-style schools of higher

learning for indigenous peoples in the New World. At Santa Cruz, sons

of the Aztec nobility were taught to read

and write Spanish, Latin, and (using the Western alphabet) Nahuafl,

their own language. Other courses were

arithmetic, philosophy, and music.

The school also enlisted renowned

Aztec healers to teach their medicinal arts. One of these Indians, who

was

given the Christian name Martinus de la Cruz, rose to the position of

Physician of the College. It was he who

made the actual compilation of plant descriptions and medicinal uses

that is now known as the Badianus

Manuscript, but the name that has become attached to it is that of his

colleague Juannes Badianus, an Indian

instructor of Latin, who rendered the text in that language. No artist

was given credit for the colorful illustrations.

Scholars theorize that de la Cruz himself painted and labeled each plate

and wrote his descriptions in Nahuatl on

separate sheets of paper, and that Badianus then did his translations

and added them to the illustrations.

The herbal, prepared at the request

of the viceroy's son, Francisco de Mendoza, was intended as a gift to

Charles

I, king of Spain. The first page begins, "A little book of Indian

medicinal herbs composed by a certain Indian,

physician of the College of Santa Cruz, who has no theoretical learning,

but is well taught by experience alone. In

the year of our Lord Saviour 1552." The medical manual crossed

the sea safely, but there is no record that it ever

came into the king's hands. A number of librarian's marks were added

inside the cover over the centuries, and the

words "Ex Libris Didaci Cortavila," scrawled on the frontispiece,

indicate that it once belonged to that Spanish

apothecary. Eventually it reached Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597-1679),

librarian of the Vatican and

cofounder of the renowned Barberini Library in Rome. In 1902 the Barberini

Library was absorbed into the

Vatican's holdings, and a mere twenty-seven years later the manuscript

was brought to light by American historian

Charles Clark. Knowledge of the Aztec healers finally reached the world

at large in 1940, when a facsimile

edition of the Badianus appeared, translated into English and annotated

by Emily Walcott Emmart. A reprint

edition, An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552, is to be issued

shortly by Dover Press.

The book's thirteen chapters deal

with close to hundred afflictions, beginning with those of the scalp

and head and

working downward. Leprosy, heart pain, venereal diseases, and "tubercles

of the breast" are considered along

with more mundane ailments such as "fetid breath," "odor

of the armpits," and "rumbling of the abdomen." The

final chapter is ominously titled "Of Certain Signs of One Who

Is Going to Die."

The medications are drawn from

animal, vegetable, and mineral sources, many of which seem preposterous

by

today's standards, such as calcareous kidney stones and the charred

excrement of various birds and animals.

(Keep in mind, however, that Premarin, a currently popular estrogen-replacement

medication, is derived from the

urine of pregnant mares.) The Badianus prescriptions commonly are for

combinations of materials, mostly of

botanical origin, such as barks, flowers, roots, and woods. The potions

pose a puzzle for modern

pharmacological researchers, who hope to tease out of each complex stew

the one molecule that may be the main

active ingredient.

Many of the plants that have been

identified are powerhouse producers of efficacious medicinal compounds.

Argemone grandiflora, a close relative of the painkilling opium poppy,

was known to the Aztecs as chicalote, an

analgesic for reducing pain in the groin. Two plates depict Dioscorea

(the genus to which true yams belong), some

species of which contain powerful steroidal sapogenins. In the 1940s

one Mexican species brought a fortune to

chemists who discovered how to synthesize the human hormones progesterone

(used in oral contraceptives) and

testosterone from chemicals held in the plant's tuberous root system.

Conspicuously absent from the volume

are most of the hallucinogenic plants found in the other Aztec herbals,

such

as the sacred cactus peyotl and the mushroom teonanacatl. Perhaps the

friars overseeing the project considered it

unseemly to recommend these to the court of Spain. The self-deprecating

tone of the introduction similarly

suggests caution: "Would that we Indians could make a book worthy

in the King's sight, for this is certainly most

unworthy to come before the sight of such great majesty. But you will

recollect that we poor unhappy Indians are

inferior to all mortals, and for that reason our poverty and insignificance

implanted in us by nature merit your

indulgence."

The illustrations are for the most

part simple and stylized, far from the photo-realist botanical renderings

we've

become accustomed to. They don't compare in accuracy with the woodcuts

in European herbals produced at

about the same time or with the botanical representations of such great

Renaissance artists as Albrecht Durer.

Nevertheless, some plants are instantly recognizable. A favorite of

mine is the depiction of huacalxochitl,

identifiable to any botanist as a member of the arum family, which includes

jack-in-the-pulpit. The flower shows

all the classic features: a white columnar spadix surrounded by a hooded

spathe, green outside and aflame with

red inside.

Other illustrations are more problematic.

In one plate, we note a plant that belongs to the potato family. The

leaves have a jagged edge, the flowers are white trumpets, the fruits

are large and fleshy. But the artist, like many

herbalists of the time, depicts the plant as a tree---on a questionable

scale--with its flowers and fruit occurring

simultaneously. These liberties tantalize. Is the plant a thorn apple

(Datura), correctly shown with upturned flowers

but incorrectly shown with smooth rather than thorny fruit? Or is it

a freely drawn angel's-trumpet (Brugmansia), a

South American native that may well have been traded in pre-Columbian

times? Other South American plants,

such as Theobroma cacao, the source of chocolate, were well established

in Mexico prior to the Spanish

conquest. In addition, plants such as vanilla and Bourreria, native

to coastal regions, and fir, native to the highest

mountains, are also portrayed--additional evidence that botanical goods

were collected and transported

throughout the Aztec realm.

The identities of many plants in

the Badianus Manuscript have yet to be deciphered, and nonochton is

one of

them. Offered for relief of pain or heat in the heart, it is part of

a prescription whose ingredients also include gold,

amber, turquoise, red coral, ocher, and the burned heart of a stag.

Its name means "little nopals that come out of

anthills," and the painting also shows red ants working among the

tuberous roots--suggesting a plant--insect

symbiosis or at least a shared preference for a particular soil. Despite

the description, it does not resemble nopal,

or Nopalea cactus. Portulaca, a succulent Mexican annual, has been suggested

as a possibility; my own guess

might be Pereskiopsis, a tree in the cactus family that has succulent

oval leaves on thorny stems.

According to Spanish priest and

historian Juan de Torquemada (1557?-1664), who drew on earlier accounts

of

the conquest, "Montezuma kept a garden of medicinal herbs, and

the court physicians experimented with them

and attended the nobility." The large aristocracy and extensive

botanical gardens, a legacy of the Aztecs' own

expansionism, helped contribute to one of the most detailed and profusely

illustrated chapters of the Badianus

Manuscript: "Trees and Flowers for the Fatigue of Those Administering

the Government and Holding Public

Office." The text promises that "indeed, these medicaments

bestow the bodily strength of a gladiator, drive

weariness far away, and finally, drive out fear and fortify the human

heart." Whether the Badianus Manuscript was

ever found "worthy in the King's sight" we shall probably

never know, but perhaps modern government officials

will be moved to bestow more funding on botanical gardens that promise

to research the plants discussed in this

chapter.

A sort of botanical time capsule,

this little book transports us back into the realm of Aztec knowledge

and yet is

also rich enough to inspire physicians, pharmacists, artists, and botanists

into the new millennium. And the

Badianus Manuscript is a worthy legacy for all who seek to heal, a common

thread wherever humans toil.

Rob Nicholson ("Az-Tech Medicine")

first learned of the 1552 Badianus Manuscript and its colorful illustrations

while taking a course with renowned Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Schultes.

Currently interim administrative

director of the Botanic Garden of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts,

Nicholson has been part of a

team studying photoecdysones in primitive gymnosperms (these compounds

help deter insects from feeding on the

plants). In addition, he is writing on botanical aspects of the paintings

of Frederic Church, a member of the

nineteenth-century Hudson River school, who also spent time in Colombia

and Ecuador. Nicholson's

plant-collecting expeditions have taken him around the world in search

of specimens for use in medical research,

conservation biology, and ornamental horticulture. He has traveled to

Mexico, Canada, Chile, Vietnam,

Colombia, Ecuador, Morocco, Algeria, the Philippines, and South Korea,

as well as around the United States.

Not a bad life, says he.

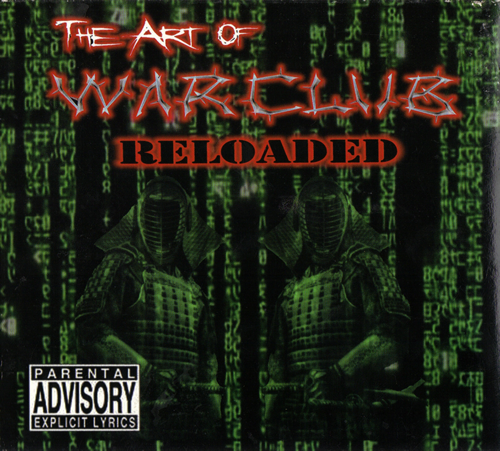

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06