The Mau Mau Uprising

The social conditions under colonial Kenya were one of the most influential factors leading to the Mau Mau uprising. The British colonial government imposed their culture upon the Kenyans way of life, which led to native resistance. The Africans understood the diversity of their country but thought they should be the ones to run it. With the arrival of educated young Africans such as Jomo Kenyatta, there was a new force to be reckoned with and the British saw their domination in Kenya slowly slipping away.

In September 1952, there began in Britain's East African colony of Kenya

an uprising that was put down only after four years of hard fighting

and over twelve thousand deaths. This uprising by African dissidents

was known as the Mau Mau which is pig latin for the word “uma

uma” and means “out out.” This movement eventually

brought colonialism to an end in Kenya, though its legacy survived after

Kenya gained its independence in 1963.

In Kenya, white settlers held a virtual monopoly over the commercial

agriculture of the fertile land. They also possessed and controlled

some of the country's secondary light industry. The balance of the secondary

and most of the tertiary industry - wholesale and retail distribution

- was in the hands of Kenya's second settler community, the Asians.

On the third and lowest rung of this colonial ladder were the Africans,

who supplied the labor.

The Europeans colonized Kenya and in the process attempted to destroy

the African culture in order to better suit their economic pursuits.

The Kikuyu had a specialized civilization and were in the process of

expanding to the south when the Europeans arrived. The Mbari was a system

of land distribution in which the githaka (land) was given to different

land owners who could trace their lineage to a common ancestor. Each

mbari had a leader called a muramati who was obliged to maintain the

land initially and develop a communal system once the population grew.

“Any member of the mbari had the right to utilize any part of

it so long as no one else had made prior claim to it and, more important,

provided the head of the mbari, the muramati, was informed.”

In Kikuyu society there was also a substantial landless population.

The difference between pre-colonial times and post-colonial times is

that the landless population in pre-colonial times were not thrown into

economic disaster. There were important social institutions which prevented

this population from becoming destitute. The landless people were known

as the ahoi and they were very important to the society although they

had no land. They basically rented land from a mbari and in return gave

a portion of his crops to the muramati. The ahoi was also obliged to

join the military and assist in the protection of the Kikuyu lands.

They were extremely important to the preservation of this fragile system

of land ownership and it was this group who would eventually initiate

the Mau Mau movement. This was an ancient system that had worked efficiently

for the Kikuyu but when the Europeans tried to break it up, it resulted

in detiorating social conditions and equally as important, it alienated

the ahoi.

In 1920, Kenya was founded in order to better stimulate economic growth

in the region through the linkage to the Uganda railway. Because Kenya

lacked minerals, the only profitable expenditure was the production

of agriculture, mainly coffee. The British government initially wanted

to colonize Kenya with a Jewish population to accomadate the urgency

of the Zionist movement. Some Europeans wanted to make Kenya an “America

of the Hindus” by colonizing it with Indians. Once Europeans settled

in Kenya, the idea of non-whites sharing land with them became greatly

opposed. The effort to encourage non-whites to colonize Kenya ended

when there was considerable anti-semitic outbursts on the part of the

resident white settlers.

The idea that the Kikuyu could assume the task of commercial farming

was out of the question because the Europeans believed they were too

primitive, ignoring the fact that the Kikuyu had engaged in subsistence

agriculture for centuries. Sir Charles Eliot held the view of many Europeans

when he stated: “the African is greedy and covetous enough….he

is too indolent in his ways, and too disconnected in his ideas, to make

any attempt to better himself, or to undertake any labour which does

not produce a speedy visible result. His mind is far nearer the animal

world than is that of the European or Asiatic, and exhibits something

of the animal’s placidity and want of desire to rise beyond the

stage he has reached.”

This racist attitude led to Kenya becoming a “white man’s

country” modeled specifically on South Africa. The Africans were

deprived of their ancestral lands and forced into a situation where

they would become wage-laborers to benefit the well being of the European

settlers. In the view of the Europeans, Africans were no more than tenants

of the imperial government and therefore had no rights to land whatsoever.

This effectively destroyed African economic independence and made way

for a colony based on cash-crops whereas the Africans would break their

backs for the rich white land owners accumulating vast wealth.

The solidification of this situation occurred in 1896 with the passing

of the Land Acquisition Act which allowed the colony to acquire any

land near the railroad they needed to make a profit. The Land Ordinance

of 1902 soon followed which enabled settlers to acquire land on a ninety-nine

year lease. The 1915 Land Ordinance is the most significant because

it increased the lease year from ninety-nine year to nine hundred and

nine years. This was an extraordinary amount of time and made it obvious

that the Europeans planned to make the fertile lands of Kenya their

permanent homes.

The problem of the encroachment of Europeans was not that they were

taking all of the land (it is estimated that overall the Europeans took

the land of only four percent of the Kikuyu population) but that the

Africans’ population was increasing dramatically. The Kikuyu adopted

European medicine which led to a sharp population increase but the Kikuyu

had always been accustomed to this trend. In historical times, the Kikuyu

had expanded far to the south and were halted only by the colonization

of South Africa. Another major problem was that the scarcity of land

led to extensive land erosion on the reserves. Therefore the fertility

was not proportionate to the land available for cultivation and the

higher demand for food led to an urgent situation.

Although the British colony had a plethora of information about the

crisis, they failed to admit that there was a problem with soil erosion

or population growth and nothing was done about the situation. The official

response to this urgent situation was to encourage migration to Tanganyika,

“civilize” the Africans thereby increasing their production

by giving them more advanced farming tools, and lastly the Africans

were encouraged to begin growing cash crops so that they can began to

buy their food instead of grow it. The option of opening land to the

Kikuyu was out of the question because the Europeans believed they would

only ruin the land with their primitive farming techniques. This was

an obvious impossibility for many Africans because people like the ahoi

had no land to begin with.

To make matters worse, the missionaries began instilling a sense of

individualism in the Kikuyu population, which led to widespread corruption.

The traditional chiefs tried to follow the traditional social rules

but when the process of individual land ownership was placed instead

of communal ownership, they were doomed. The important tribal unity

that had lasted for centuries was now being rapidly disintegrated. The

new chiefs now accepted bribes in exchange for their ancestral lands

and intimidated anyone who spoke out against them.

The traditional chiefs had lost their power to younger men who had been

appointed by the British. These new chiefs were tempted with their newfound

power and had been corrupted with Westernization. It was now possible

for these new chiefs to neglect their traditional duties without fear

of being punished. The British control had been felt and the power of

the traditional elders was quickly diminished. This led to a clash between

the older and younger generations. The old people insisted upon continuing

their culture and the social roles held within but the young people

felt it impossible or undesirable to maintain such traditions in this

new fast changing society. According to Jomo Kenyatta, the problem lay

in the complete annihilation of “the tribal democratic institutions

which were the boast of the country, and the proof of tribal good sense,

have been suppressed.”

The Africans were placed on reserve lands in order to create more land

for settlers and also to force them into seeking a livelihood as laborers

on European farms. This had disastrous effects for the entire population

but it hit the ahoi the hardest. Because the ahoi had no formal rights

to land, they had no right to live on the reserves. They were thus left

landless and their former symbiotic relationship with the mbari had

now completely disappeared. The ahoi were now forced to choose between

becoming servants of the land owners or go to the cities and become

laborers in slums. According to the Carter Land Commission, by 1934,

110,000 Kikuyu were living outside the reserve and by 1948, this number

increased to 294,146.

The ahoi and the Kikuyu with too little land to support their families

began swarming to the city of Nairobi. In the cities, an urban laborer’s

lot was low pay and appalling living conditions. In the country, colonial

farmers employed African labor either on monthly terms or under a system

that resembled medieval villeinage. In this second system, 'resident

laborers' or 'squatters' worked for a settler for two hundred days a

year in return for a meager wage and the use of a plot of land to grow

their own food. The remainder of the African population was engaged

in subsistence agriculture in ethnic 'reserves', growing cheap food

for the urban workers.

“By 1948 there were 28,886 Kikuyu living within the municipality

of Nairobi, 45% of the total African population in the city.”

The industrial development in Kenya overall was too limited to provide

for this incredible influx and most remained either unemployed or were

absorbed in low paying manual work. The colonial state justified these

low wages by claiming the African laborers did not depend on them to

survive which was a far cry from reality. The highest paid African male

worker earned about one-tenth of the wages received by the lowest-paid

male European worker. These were desperate people, mostly men who hoped

to earn enough money to buy land on the reserves or at least for a suitable

bride price. Another large population of demobilized ex-servicemen who

had served in World War II came to Nairobi because unlike their white

counterparts, the government had not provided them with land or aid.

Not unlike the Africans in America, the Kikuyu were forced into slums

where the housing was inadequate for the crammed population; often lacking

even sanitary requirements. The Africans became stuck in these slums

unable to accumulate enough wealth to buy land back home. They even

failed to earn a living wage due to incredible inflation and the government’s

reluctance to raise their wages.

All of this culminated into the first social movement in rebellion against

the colonial state in Kenya. The choice was non-violent resistance with

the facilitation of trade unions. Led by Chege Kibachia the urban Kikuyu

began the African Worker’s Federation, an all-African trade union

seeking immediate solutions to the plight of thousands of African workers.

After several attempts at peaceful striking, it became apparent that

the colonial government was not willing to succeed to any African demand.

Kibachia’s trade union soon collapsed and in its place came the

East African Trade Union Congress (EATUC) founded by Fred Kubai a Kikuyu

activist and Makhan Singh, an Asian communist. The colonial state responded

to the EATUC general strikes with a considerable show of force and in

1950, the organization was banned; leaving the workers with no trade

union to resolve their economic plight.

The repression of their trade unions led many activists to believe that

the colonial government would not respond to non-violent resistance

and the road to peaceful negotiations was effectively closed. The urban

Kikuyu instead turned to violence and crime in order to survive in their

increasingly hostile environment. Criminal groups using their kinship

ties as gang identities appeared all over Nairobi. After 1947, the incidence

of crime in Nairobi increased dramatically and there were not enough

police powers to stop its growth. These gangs easily took control of

the many areas lacking an adequate police force. Racial hostility rose

and Africans began to develop a local hatred against the colonial state.

Education before the coming of the Europeans was undertaken by parents

and elders in the society. An ingenious form of games, riddles, stories

and instructions concerning the correct behavior to adopt was taught

emphasizing the importance of personal relations. The basic knowledge

that was taught to the children was necessary to ensure that the identity

of the tribe would be passed on.

The first missionaries came to Kenya in 1844, even before the British

government claimed it as their own. Their style of education was vastly

different and focused on basic literacy for reading the Holy Bible,

and manual tasks were implemented for their “moral” value.

The missionaries attempted to create self-sufficient Christian communities

who would spread the word to the surrounding population through their

example. Although the settlers attempted to convert the Kikuyu to Christianity

they were not very successful. The Kikuyu relied heavily on their native

religion and their concept of Ngai. Many of the African societies resisted

the missions and the missionaries found they had to turn to the idea

of recovering slaves that the British had captured in their campaign

to stop the slave trade.

A powerful new force came out of these missionaries and foreign schooling.

A growing number of Western educated Africans were rising up to represent

their impoverished brethren in the name of nationalism. They had learned

of the colonial structure, they could speak the settlers’ language,

and most importantly they could write in the settlers language. These

young Africans were in a position to create a powerful new force the

colonial government would have to deal with.

Led by such leaders as Harry Thuku and Jomo Kenyatta, new organizations

appeared varying in their philosophies. Some were led by Christians

and were conservative, others were led by Africans activists and were

extremely radical. Organizations such as the KA, EAA, KCA, NKCA, UMA,

and KAU were instrumental in illustrating the plight of Kenyans and

proposing solutions for the problems. They were all for the most part

separate organizations but in 1950 they decided to unite using oaths

which would instill courage into the initiates. Many of the dispossessed

in Nairobi and the squatters in the Rift Valley Province were eager

to take the oath as it was their last hope.

The forty thousand white settlers lived among some 5.6 million Africans

whom they alternately patronized and feared. They did not see it as

their role to encourage the Africans' economic and political aspirations,

which had been raised during World War II when many Kenyans had fought

for 'king and country'.

In addition, the whites could not see that the failure to implement

long-promised land reform was, in the postwar years, placing an intolerable

burden on the African population. It fell most heavily on the pastoral

Kikuyu, the largest of Kenya's tribes, whose land was wholly inadequate

to accommodate either a growing population or returning squatters.

Colonial rule, while not overtly oppressive, operated through 'agreement'

with white settlers. African political representation was all but ignored.

This complacent climate led to what was, in effect, a peasant revolt,

an uprising of the poor and dispossessed that shook the colonial structure

to its foundations.

The Mau Mau did not constitute a national uprising, as only members

of the Kikuyu and two smaller related ethnic groups, the Embu and Meru,

took part. The other Kenyan African peoples remained indifferent or

opposed to the aims and the methods of the Mau Mau. And the educated

elite among the Kikuyu opposed the strategy of the movement even if

they sympathized with the aim of changing the colonial order.

Although conceived in the early 1940s, it was not until 1952 that the

Mau Mau launched attacks on white farmers - the first wave was, in fact,

targeted against African chiefs and headmen who were loyal to the British.

In October 1952 - when there were some twelve thousand African guerrillas

in the field - a state of emergency was declared by the governor, Sir

Evelyn Baring.

Simultaneously, British troops began arriving by air from Egypt and

the United Kingdom to reinforce the British-officered King's Africa

Rifles. Eventually dispatched to Kenya were naval, artillery engineer

and Royal Air Force (RAF) elements, the last equipped with light bombers.

The Kenya Regiment, whose ranks were filled with the sons of white settlers,

was also mobilized, and the Kenya police reinforced until they were

as heavily armed as the army regulars. At its height, the campaign involved

five British infantry battalions, six battalions of the King's Africa

Rifles, two RAF bomber squadrons and a greatly expanded police force.

The colonial administration's next step was to arrest Jomo Kenyatta,

a British-educated African who, on the publication of his book Facing

Mount Kenya in 1938, had become the spokesman for Kenyan nationalist

aspirations. The British believed that Kenyatta was the master strategist

behind the Mau Mau, when, in fact, he was opposed to violence. Following

a trial at which (it is now freely admitted) both the judge and the

chief witness were bribed, the British sentenced Kenyatta to seven years'

imprisonment - and, at a stroke, removed from the scene the one man

who might have prevented the situation worsening.

In January 1953, the settler community was convulsed by the murder of

a white farmer, Roger Ruck, and his wife and small son. All three had

been hacked to death by pangas. A crowd of one thousand five hundred

settlers marched on Government House in Nairobi to demand the use of

any and all means to crush the Mau Mau. Most white settlers took to

carrying guns at all times, and their wives and teenage children were

instructed in their use. 'Loyalist' Africans were formed into 'Home

Guard' units to defend isolated farms, which were turned into fortresses.

Two months later, the killing of the Rucks was followed by the massacre

at Lari of at least seventy four loyalist Kikuyu, including the elderly

Chief Luka. 'Home Guards' returning from a patrol found their homes

destroyed and their families dead.

By now, word of Mau Mau oath-taking ceremonies had reached the ears

of the settlers. Although these were later described by a white former

official in Kenya as the equivalent of taking a Boy Scout oath, the

fact that they involved certain things sacred to Kikuyu culture - for

instance, goat meat and blood - appalled the white population, and wildly

inaccurate stories spread.

The two massacres completed the demonisation of the Mau Mau in the minds

of the settlers, and the white community was seized with a desire for

revenge at any cost. The Mau Mau, with what the whites saw as their

grisly oath-taking ceremonies, were seen as the incarnation of the settlers'

fear of unbridled native savagery.

In the spring of 1954, British troops launched a major search and cordon

operation, codenamed 'Anvil', in and around Nairobi. In the course of

six weeks, most of the city was searched and some twenty thousand Kikuyu

arrested and detained without trial. The operation succeeded in severing

permanently the links between the political arm of the Mau Mau in Nairobi

and the guerrilla groups operating to the north, in the dense forests

of the Aberdare range and around Mount Kenya.

From their secret forest bases, Mau Mau raided settler areas throughout

central Kenya, especially those containing loyalist Kikuyu, most of

whom were eventually herded into protected settlements - a policy known

as 'villageisation'. In the Mau Mau units, women fought alongside men,

sometimes leading the men into battle. The women were crucial in the

organization and maintenance of the supply lines, which directed food,

supplies, medicine, guns, and information to the forest forces. Those

women who joined the men in the forest were responsible for cooking,

water hauling, and knitting sweaters among many other important roles.

Large British sweeps, operating at first with very little intelligence,

failed to inflict heavy damage on the Mau Mau in the forests. The latter

were, in the main, poorly armed, but their fieldcraft was superb, enabling

them to melt into the trees when threatened. Later, the British employed

more effective methods, using smaller units guided by African trackers.

But it was two big sweeps in 1955-6 - 'Hammer' and 'First Flute' - which

broke the back of the Mau Mau in the forests.

The British also employed terror. In an anticipation of the 'free fire

zones' of Vietnam, 'prohibited' areas - the Aberdares, Mount Kenya and

a mile-wide strip around them - were established in which any African

could be shot on sight; these areas were also bombed by the RAF. Rewards

were offered to the units that produced the largest number of Mau Mau

corpses, the hands of which were chopped off to make fingerprinting

easier. Settlements suspected of harboring Mau Mau were burned, and

Mau Mau suspects were tortured for information.

In 1956, the charismatic Mau Mau leader, Dedan Kimathi, was wounded

and captured. Kimathi was an intriguing figure, a self-styled 'field

marshal', who maintained discipline through the gun and the garrotte.

He always carried with him the Bible and a copy of Napoleon's Book of

Charms, which he used as an oracle. He was hanged in January 1957, despite

having converted to Catholicism. His death brought an end to organized

Mau Mau resistance.

For the colonial administration, the problem remained of what to do

with the thousands of Mau Mau in detention who refused to break their

blood oaths, which, for the whites, had taken on an almost mystical

significance. Psychological pressure was brought to bear, including

staged confrontations with tribal elders that sometimes turned violent.

In spite of these efforts, the men detained at Hola Camp refused to

repudiate their oaths. In 1959, with the approval of their officers,

British soldiers severely beat some 80 of these men, an incident that

led to the deaths of eleven and seriously injured dozens more.

The British attempted a cover-up, claiming that the men had died after

drinking tainted water. But in the House of Commons, there was a dramatic

debate on the Hola deaths in which the Conservative government's explanations

were clinically destroyed by MPs Barbara Castle and Enoch Powell.

In the wake of the Hola scandal, the camps were closed, the detainees

released and the state of emergency lifted. No more was heard of the

Mau Mau oath. The Lancaster House conference of 1960 was followed by

a greater measure of democracy for the Africans, heavy government aid

for African agriculture and improved wages for urban workers. In anticipation

of independence, the coming of which had been accelerated by the Mau

Mau uprising, increasing numbers of Africans were promoted within the

public service.

In 1963, Kenya achieved independence, with Jomo Kenyatta as its first

president. The men and women who had taken to the hills after Kenyatta's

arrest may not have heard Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's 1960 'wind

of change' speech in South Africa, but they had certainly influenced

it.

However, most of these same men and women who had fought for the Mau

Mau gained little benefit. In newly independent Kenya, they were excluded

from public life and preferment, the spoils of independence going to

the wealthy and educated Africans who had a vested interest in marginalizing

them. A black elite simply replaced the white one.

In the Mau Mau uprising, thirty European and twenty-six Asian civilians

were killed. Of the Kenyan security forces, five hundred and ninety

were killed, of whom sixty-three were European. At the height of the

emergency, civilian deaths ran at about one hundred a month, the great

majority of them loyalist Kikuyu. Mau Mau deaths are estimated at eleven

thousand and five hundred.

The main causes of the Mau Mau uprising was the harsh restrictions placed

upon African way of life. The social conditions were so appalling that

after awhile there was nothing left to do but uprise against the oppressor.

The Africans in Kenya did this with the help of leaders such as Jomo

Kenyatta who attacked the wretched social conditions his people were

forced to live in under British domination.

The detrimental social conditions in Kenya and specifically among the

Kikuyu precipitated the Mau Mau movement. The British occupation of

Kenya led to a systematic destruction of the African way of life. The

introduction of white settlers, missionaries, and land acts had a detrimental

effect on the diverse cultures living in Kenya. This extreme tension

caused by the oppressive settler government was insurmountable and eventually

led to the Mau Mau uprising.

Baldwin, William. Mau Mau Man-Hunt. New York; E.P. Dutton & Company

Inc., 1957.

Bennet, George. Kenya: A Political History. London; Oxford University Press, 1963.

Cox, Richard. Kenyatta’s Country. New York; Frederick A. Praeger, 1966.

Delf, George. Jomo Kenyatta. New York; Doubleday, 1961.

Edgerton, Robert B. Mau Mau: An African Crucible. New York; The Free

Press, 1989.

Hobley, C.W. Kenya: From Chartered Company to Crown Colony. London;

Frank Cass and Company Limited, 1970.

Hughes, A.J. East Africa: The Search for Unity Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, and Zanzibar. Baltimore; Penguin Books, 1963.

Huxley, Elspeth. Nine Faces of Kenya. New York; Viking Penguin, 1990.

Huxley, Elspeth. Settlers of Kenya. Connecticut; Greenwood Press, 1975.

Huxley, Elspeth. White Man’s Country. London; Chatto and Windus

Ltd, 1956.

Lambert, H.E. Kikuyu Social and Political Institutions. London; Oxford

University Press,1965.

Leakey, L.S.B. Mau Mau and the Kikuyu. London; Metheun & Co. LTD., 1953.

Leakey, L.S.B. Defeating Mau Mau. London; Metheun & Co. LTD., 1954.

MacPhee, Marshall. Kenya. New York; Frederick A. Praeger, 1968.

Maloba, Wunyabari O. Mau Mau and Kenya: An Analysis of a Peasant Revolt.

Indianapolis; Indiana University Press, 1993.

Mungeam, G.H. British Rule in Kenya 1895-1912. London; Oxford University Press, 1966.

Murray-Brown, Jeremy. Kenyatta. New York; E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1973.

Nelson, Harold, ed. Kenya: a Country Side. Washington, D.C.; American

University, 1984.

Roberts, John S. A Land Full of People: Life in Kenya Today. New York; Fredrick A. Praegar, 1966.

Rosberg, Carl and John Nottingham. The Myth of “Mau Mau”: Nationalism in Kenya. New York; Frederick A. Praeger, 1966.

Ross, W. McGregor. Kenya From Within: A Short Political History. London;

Frank Cass and Company Limited, 1968.

Sheffield, James R. Education in Kenya: An Historical Study. New York and London; Teachers College Press, 1973.

Sorrenson, M.P.K. Land Reform in the Kikuyu Country. Nairobi; Oxford University Press, 1967.

Wood, Susan. Kenya: The Tensions of Progress.

London; Oxford University Press, 1960.

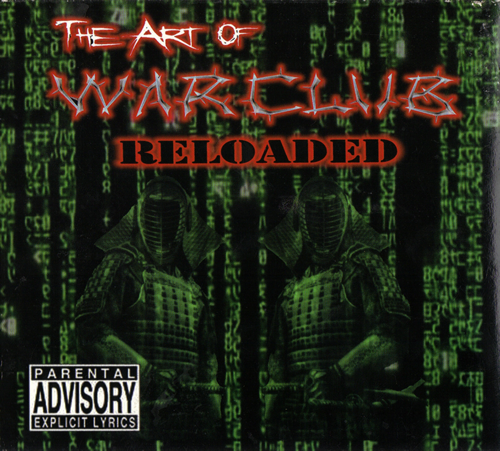

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06