Full content for this article includes table

and illustration.

Source: Nutrition Today, May-June 1992 v27 n3 p13(13).

Title: Aztec patterns and Spanish legacy. (Nutrition Past - Nutrition

Today: Prescientific Origins of Nutrition and Dietetics, part 4)

Author: Louis E. Grivetti

Subjects: Aztecs - Food and nutrition

Native Americans - Medicine

Medicine, Ancient - Nutritional aspects

Allopathy - History

Dietetics - History

Spaniards in Mexico - Food and nutrition

Electronic Collection: A12448850

RN: A12448850

Full Text COPYRIGHT 1992 Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins

For thousands of years the peninsula of Iberia

in southwestern Europe was a

crossroads of competing cultures, civilizations and religions. Roman

patterns

of allopathic medicine with accompanying hot-cold designations were

introduced

there several centuries before the Common Era. Situated on the Mediterranean

western rim, Iberia was intellectually isolated from the Greek medical

teaching centers. This isolation changed, however, as a result of three

historical events: the Jewish diaspora after the Roman conquest of Jerusalem

in the 1st century A.D.; the domination of Christianity throughout

Mediterranean lands in the 4th century; and the rise of Islam in the

Arabian

peninsula and its spread across northern Africa during the 7th century

A.D.

On July 19th, in the year 711 A.D., Mushm armies

massed in northwestern Africa

and invaded Iberia. One result of this African religious invasion of

Europe

was an astonishing cultural transformation, a fusion of

Christian-Jewish-Muslim art and architecture, culture and language and

medical-nutritional practices. In the centuries after this invasion

there

evolved in southern Iberia a unique medical system that integrated Christian,

Jewish and Muslim traditions. Three complementary systems of allopathic

medicine and "hot-cold' concepts were taught at universities and

medical

schools at Cordova, Granada and elsewhere.

As Europe declined into the Dark Ages, two great

geographical centers of

enlightenment and learning emerged in the Mediterranean basin: an eastern

complex that included physicians who practiced in the great eastern

cities of

Antioch, Baghdad, Cairo, Constantinople, Damascus and Jerusalem, and

a western

cluster of universities in Iberin. Later, a third center of medical

thought

developed during the 11 th and 12th centuries on the Italian peninsula,

expressed by important contributions from the hospital at Monte-Casino.

Most

influential of the Italian medical schools, however, was Salerno, near

Naples,

a center of Christian, Jewish and Muslim intellectual leadership whose

publications influenced Iberian allopathy into the 16th century at the

time of

the Spanish Portuguese voyages of exploration.

SALERNO AND THE REGIMEN SANITATIS

The teaching hospital at Salerno rounded in 1150

A.D. evolved as one of the

bright centers of learning in an otherwise dark European era. Contributions

to

medicine, nutrition and dietetics attributed to scholars at Salerno

reveal a

creative approach to allopathy and the use of food in healing. One of

the

interesting texts readily available today is the Regimen Sanitatis

Salernitatum, dated to the 13th century A.D. The Regimen, originally

composed

in Latin, was subsequently translated into modern European languages,

and

appears even in Gaelic.(1) It has remained a popular medical text and

may be

read in English either as poetry or prose, although the latter is preferred

because of latitude taken by poets who "stretched" the meaning

of medical

terminology to conform to rhyming patterns.

The Regimen reveals a wealth of information on

allopathic, humoral, hot-cold

medicine, especially the role of food and dietetics in Mediterranean

Europe,

and highlights concepts widely practiced in Iberia on the eve of Spanish

contact with the New World:

To keepe good dyet, you should never feed

Until you finde your stomacke cleane and void

Of former eaten meate, for they

do breed

Repletion, and will cause you soone be cloid,

None other rule but appetite should need,

When from your mouth a moysture cleare doth void.

All Peares and Apples, Peaches, Milke and Cheese,

Salt meates, red Deere, Hare, Beefe and Goat: all these

Are meates that breed ill bloud, and Melanacholy,

If sicke you be, to feede on them were folly. And:

Eate not your bread too stale, nor eate it hot,

A little Levend, hollow bak't and light:

Not fresh of purest graine that can be got.

The crust breeds choller both of browne and white,

Yet let it be well bak't or eate it not,

How e're your taste theren may take delight.

Porke without wine, is not so good to eate

As Sheepe with wine, it medicine is and meate

Tho Intrailes of a beast be not the best,

Yet are some intrailes better than the rest. Elsewhere:

If to an use you have your selfe betaken,

Of any dyer, make no sudden change,

A custome is not easily forsaken,

Yea though it better were, yet seemes it strange,

Long use is as a second nature taken,

With nature custome walkes in equall range.

Good dyet is a perfect way of curing:

And worthy much regard and health assuring.

A King that cannot rule him in his dyet,

Will hardly rule his Realme in peace and quiet.

Perhaps the most famous passage from the Regimen,

however, is a recommendation

on medical selftreatment: "If you lack doctors, these three will

serve you: a

cheerful mind, rest and a moderate diet," sometimes translated

as good humor,

rest and sobriety (Harington, 1957).

THE TACUINUM SANITATIS Other medieval European

documents influenced the

evolution of 16th century Iberian, Spanish medicine and dietetics. Five

illuminated medieval manuscripts survive with the collective name Tacuinum

Sanitatis (health handbook). These manuscripts, beautifully illuminated

were

used throughout Mediterranean Europe from Iberia to Greece. They contain

information on self-healing and identify six factors that all so-called

educated persons should recognize and understand, if they wished to

remain in

good health: 1) attributes and qualities of air, 2) proper use of food

and

beverages, 3) correct principles of human activity and sleep, 4) treatments

for insomnia, 5) principles of correct elimination or retention of humors

and

6) techniques to counter adverse effects of anger, fear, distress and

joy.

The Tacuina originally were composed in Arabic

by a Christian physician during

the 11th century A.D. By the 14th century these texts had circulated

widely

throughout southern Europe and Iberia. Although the Tacuina were based

on

Arabic medicine, their content can be traced historically to classical

Greek

and Roman accounts originally authored by Celsus, Galen and Hippocrates

(Grivetti, 1991b). Each handbook provided healing designations for

Mediterranean foods, then defined and described their various attributes.

The

texts also posed and answered questions on appropriate seasonality,

food

preparation and combinations. Consumables were designated by their perceived

inherent nature, whether "hot-dry," "hot-wet," "cold-dry,"

or "cold-wet," and

by optimum source, defined as either fresh or preserved and by best

geographical location. Appropriate medical-dietary uses and impacts

on

specific body organs were identified, defined and explained. Foods also

were

evaluated, then recommended or discouraged in accord with the consumer's

occupation. Perceived dangers associated with consumption were identified

and

specific counteractions listed (Arano, 1976).

The Tacuina identify more than 200 foods common

to Iberia and the southern

Mediterranean; a selection is presented in Table 1. Beef, for example,

was

considered "hotdry," deemed useful for persons engaged in

hard labor, and veal

was perceived the optimal source of beef. Overconsumption reportedly

injured

the spleen. Diseases of the spleen could be avoided, however, if beef

consumers exercised regularly after eating and bathed. Pork, in contrast

to

beef, was designated "hot-wet," and reportedly nourished the

body. Eating too

much pork, however, was said to harm the stomach unless it was well

roasted

and eaten in combination with mustard. Pears, assigned to the "cold-&y"

category, were said to strengthen the stomach. Ripened pears were considered

optimum, but eating too many was said to provoke colic unless eaten

in

combination with other undefined foods. Lettuce, in contrast, was designated

"cold-wet" with attributed properties that countered insomnia.

Fresh leaves

were optimum, but would injure human eyesight unless eaten with celery

(Arano,

1976).

SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE ALLOPATHY: CONNECTIONS BEYOND IBERIA

Mediterranean allopathic, "hotcold"

concepts formed the core of Iberian,

Spanish medicine during the Middle Ages. These concepts, familiar to

all

educated Mediterraneans, were brought to new territories wherever Italian,

Portuguese and Spanish explorers and armies landed in successive centuries.

Patterns of Mediterranean allopathy and use of food to treat disease

spread

widely during Portuguese conquests in Africa and Asia. Iberian allopathy,

likewise, was transferred westward with Columbus in 1492 and diffused

throughout the Caribbean. During the next 25 years Spaniards arrived

in the

New World as administrators, conquistadors, priests or teachers, and

brought

with them, too, the rich medicaldietary heritage of Iberia.

AZTEC MEDICAL-FOOD SYSTEM

The earliest accounts and descriptions of the

New World written between 1492

and 1612 may be found in most libraries. These accounts contain wonderful

descriptions of food, diet and medical practices and excite nutrition

historians even today. One intriguing point from the perspective of

the

history of prescientific nutrition and dietetics is that the accounts

in these

texts reveal that allopathic, "hot-cold"| concepts pre-existed

within the

Aztec civilization of modern Mexico well before arrival of the Spanish

in

1519.

Like the allopathic medical-dietary systems of

other cultures, the Aztec

pattern was based upon religion and mythology. The Aztecs conceived

the earth

as a plane with four cardinal directions. At the central point or balance

within the plane lay the Aztec empire. The five localities were assigned

characteristic colors and attributes: West-- white, female, house; East--red,

male, reed; Center--green, order, equilibrium-balance; North--black,

death,

flint; and South--blue, life, rabbit. The Aztecs also conceived a structured

world based upon 18 sets of paired terms (Table 2). Especially prominent

within these dichotomies were designations for "hotcold,"

"dark-light,"

"humiditydrought" and "weakness-strength." Of the

18 terms identified by

literate Spanish conquistadores at the time of contact in 1519, six

terms were

similar to those developed within Mediterranean allopathy, but 14 of

the 18

paralleled the Asiatic, Chinese pattern of prescientific dietetics.(2)

A pantheon of seven Aztec deities dominated the

pre-Spanish Mexican

medical-dietary system: Tzapotlatenan, creator goddess of the earth

and sky,

and principal medical deity; Xipe or Totec, god of maize and human sacrifice;

Ixtilton or Tlaltecuin, god of medicine and protector of children; Centeotl

or

Tonantzin, goddess of medicinal herbs and midwives; Cihuacoatl or

Macuilxochilquetzali, goddess of pregnancy; Quetzalcoatl, god of air,

wind and

medicine, responsible for female sterility and wind-related diseases

such as

rheumatism; and Tlaloc, god of rain, responsible for the distribution

of

disease (de la Cruz, 1940, pp. 42-44).

In Aztec tradition health was perceived as "balance,"

illness and disease as

"imbalance." Equilibrium, however, was not easy to maintain

since balance

changed seasonally and in accord with human age, gender, personality

and

exposure to environmental temperature extremes. Sexual activity also

influenced "balance," as did physiological conditions of lactation,

menstruation and pregnancy. Central to the Aztec system, too, was the

concept

that "balance" was effected favorably or adversely by diet.

Diseases and medical problems were assigned to

one of three categories:

supernatural illnesses, which included gout, leprosy, paralysis and

rheumatism, thought to be produced by spirits of women who had died

during

childbirth; magical illness, which resulted because of inappropriate

human

behavior resulting in disease as a punishment from the gods; and natural

illness, defined as obvious problems that included fractures, sprains

or snake

bite. In the Aztec system diseases of the first two types were transmitted

through air and distributed by wind (de la Cruz, 1940; Ortiz de Montellano,

1990; Vargas, 1984).

SPANISH VIEWS ON AZTEC MEDICINE AND DIETETICS

Troops commanded by Hernando Cortes landed on

the east coast of Mexico in

1519. Within 2 years they subdued and conquered a great empire and established

the European colony of New Spain. In successive decades after conquest,

Spanish administrators rounded medical schools where European concepts

of

allopathy and diet were taught for the first time on the American continent.

During the first centuries of colonization, Spanish administrators,

educators,

priests and soldiers imposed European civilization upon the conquered

Aztecs,

then upon the Inca, Maya and other Native Americans. This process of

"Europeanization" and conversion to Christianity was responsible

for the

destruction of countless manuscripts that detailed the specifics of

Aztec

medicine and dietetics. Such were the events and attitudes of religious

zealots who viewed these ancient texts as godless and without redeeming

value.

Within this frenzy of cultural destruction imposed

by the majority, a minority

of Spaniards sympathetic and curious about Aztec cultural traditions,

medicine

and dietetics, technology and world view protected and preserved some

original

Aztec documents. This body of Aztec literature, a mere fragment of works

that

once existed in greater detail, may be examined today. In addition,

there are

the accounts written by the early Spanish that described Aztec food

and

dietary practices, their system of medicine.

Bernal Diaz del Castillo (1956) accompanied Hernando

Cortes on the Spanish

invasion, overland march and conquest of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

In

his memoirs he described with wonder the vast array of food available

in the

great open-air market in the Aztec capital. His text is the first

documentation for "fast-food" in the Americas: There were...

traders who

sold.., cacao [chocolate]... There were those who sold... sweet cooked

roots

... [others] sold beans and sage and other vegetables and herbs ,..

fowls,

cocks with wattles [turkeys], rabbits, hares, deer, mallards, young

dogs...

let [me] also mention the [fruit sellers], and the women who sold cooked

food,

dough and tripe in their own part of the market (1956, pp, 216-217),

Francisco Bravo (1570) wrote the first medical

book published in the New

World, Opera Medicinalia. His text consisted of four essays: a discussion

of

typhus and typhoid fever (European diseases introduced after Spanish

contact);

how to bleed patients (venesection); a review of the ancient Greek,

Hippocratic doctrine of critical days and discussion of the classification

and

treatment of fever; and an essay on the medical properties and allopathic

nature of sarsaparilla (Smilax officinalis), a New World plant used

by the

Spanish to treat fever and syphilis, which he designated "hot-dry."

Bravo also

cautioned against eating fish in Mexico, maintaining that fish in the

swamps

and lakes surrounding the capital caused disease.(3) He commented, too,

that

Spanish colonists living in the former Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan,

were

vulnerable to disease because the surrounding mountains prevented removal

of

"foul air" (Bravo, 1570; Jarcho, 1957).

Francisco Hernandez (1577) documented Aztec medical

practices and noted

parallels with Mediterranean, Spanish medical systems. In his text,

De

Antiquitatibus Novae Hispaniae, he wrote that dietary recommendations

were not

made to ill patients and that the sick were bled in a manner similar

to the

common practice of Mediterranean allopathic medicine. Hernandez documented

a

wide range of useful medical plants from New Spain, but wrote that most

Aztec

physicians were ignorant of basic botanical "properties,"

by which he meant

Mediterranean "hot-cold" designations and other useful properties

defined in

documents such as the Arabic-Latin, Regimen and Tacuina (Hernandez,

1577;

Peredo, 1985).

Augustin Farfan (1592) wrote Tractado Brebe de

Medicina (two editions) wherein

he identified and recommended local Aztec herbs, their properties and

medical

uses. He noted that avocado seeds were ground to powder, then prepared

as a

concoction to counter diarrhea, observed that chili peppers, rhubarb

and

vanilla were commonly used by the Aztecs as purgatives, and that chocolate

brewed as a thermally hot beverage was a traditional laxative. He described

an

Aztec method to counter colic: maize tortillas were heated, then applied

directly onto the patients' abdomen to reduce pain (Risse, 1987),

Farfan's texts are enlightening not only for

their descriptions of Aztec

medical and food-related practices, but for observations on early Spanish

colonists, especially their putative idleness, lack of strenuous activity

and

gluttony:

The foods eaten in Mexico are hot and humid,

conforming to the humoral

complexion of the country, and hence are weak, whereas the foods of

Spain are

solid and nutritious. In Spain people are healthier than in Mexico and

[they]

live longer. The idleness so prevalent in Mexico is conducive to overeating

and over drinking (1579, 1st ed., p. 223).

At all hours of the day and many hours of the

night [Spanish women of New

Spain] can be seen eating dainties; especially cacao is eaten and drunk...

Other women stuff themselves with chocolate which .., [is] bad for

digestion... [because] these things fatten the blood and obstruct and

cover

the veins (1592, 2nd ed., p. 33).

AZTEC MEDICINE: THE BADIANUS MANUSCRIPT

Perhaps the most important source on Aztec medicine

and diet known is the

Badianus Manuscript. Its author was an Aztec teacher, with a "Europeanized"

name, Martinus de la Cruz, at the College of Santa Cruz rounded by the

Spanish

circa 1536 in a suburb of Mexico City. He wrote the manuscript in his

native

tongue, Nahuatl, which was then translated into Latin by another Aztec

teacher

with the Europeanized name, Juannes Badjanus. The manuscript presents

a wealth

of information on Aztec disease concepts, religion and world view, and

outlines the healing properties of local animal, vegetal and mineral

medicines. De la Cruz recorded the Aztec tradition that diseases were

dispersed by and carried on the wind, and that in cautious human exposure

to

temperature extremes of weather, especially the heat of deserts and

the cold

of high mountain areas, predisposed the human body to disease. He also

wrote

that lack of attention to body cleanliness, specifically bathing, contributed

to illness (De la Cruz, 1940, pp. 3-51).

Excerpts from the Badianus Manuscript reveal

the Aztec view that food was

important to healing and that "hot-cold" assignments predated

Spanish contact,

and provide descriptions and treatments for a range of New World diseases.

Some of these treatments are nutritional in nature:

Angina: [Grind] white earth, the many-colored

little stones or pebbles...

collected from brooks [along with] flowers [of] huacalxochit(4) and

tlacoyzquixochit,(4) the juice well pressed out, which [the physician]

should

then pour into the throat repeatedly (Plate 30, p. 234).

Gout: If the foot is bothered with much heat,

it is to be moistened with cold

juice; if, on the other hand, the foot is extremely cold, it is to be

warmed

(Plate 62, p. 267).

Headache: Eat onions in honey, [do not] sit in

the sun, [do not] work, and do

not enter the baths (Plate 7, p. 209).

Indigestion: When any one is constipated because

of indigestion of the

stomach, grind together... cones of cypress, laurel leaves, stalk of

the herb

zacamatlalin,(4) bark of the blackberry bush, root of cherry and the

ylin(4)

tree and of the herb tonatiuhyxiuh(4) .... And when ground they are

to be well

cooked in acid water with honey; the juice when drunk helps marvelously

to

purge the abdomen (Plate 87, p. 298).

Elsewhere in the manuscript specific attention

is directed to maternal and

child health, especially problems associated with breast feeding:

To promote lactation: When the milk flows with

difficulty, the herb[s]

chichilticxiuhtontl,(4)tohmiyoxihuit,(4) and a crystal are to be crushed

in

octIi [fermented sap of maguey] and boiled. The potion is to be drunk

frequently ... [and]... the woman should... enter a bath, where she

is to

drink another potion made of maize [and] when she comes out she is to

take as

a drink the sticky water of boiled maize (Plate 111, pp. 319-320).

To promote infant sucking: If the infant ...

does not wish to put his lips to

his mother's breasts, give him a drink of the sma11 herbs called teamoxtli,(4)

the sun dried liver of a quail, and some of his hair which you have

cut off,

and which you should burn to ashes. [Rub] him with an ointment carefully

made

from the brain of a weasel and a burned human bone, which you are to

dissolve

in acid water (Plates 113 and 114, p. 322).

The Badianus Manuscript index provides commentary

on approximately 100 medical

conditions. Of these, 10% are nutrition or foodintake related and include

reference to conditions of angina, constipation, dental problems (tartar

removal), dysentery, dyspepsia-indigestion, fatigue, gout, heart (overheated),

hemorrhoids and lactation difficulties. No references appear in this

manuscript that could be equated with beriberi, pellagra, rickets or

scurvy,

or to medical-nutrition related conditions such as cancer, diabetes

or stroke.

AZTEC MEDICINE: A 20th CENTURY PERSPECTIVE

Other texts document nutritional problems among

the Aztecs, including heart

disease, kwashiorkor(5) and obesity. Ortez de Montellano (1990) wrote

that

traditional Aztec diet apparently was low in saturated dietary fats,

given

only modest intake of meat and the lack of dairy products before the

Spanish

conquest. He suggested that such a pattern, coupled with a presumed

high level

of physical activity among Aztec workers, would minimize cardiovascular

disease. Yet his review of surviving Aztec documents identified heart

ailments

such as angina and "overheated heart."

Lopez Austin (1988) reviewed Aztec manuscripts

and accounts by 16th century

Spanish priests and physicians practicing in Mexico. He concluded that

the

Aztecs had a sophisticated medical system that predated Spanish contact.

Aztec

healers used food and medicines to balance "hot-cold" relationships

and to

transfer disease from one part of the body to another part where it

could be

more easily cured (see quotation at the beginning of this article).

The Aztecs had a sophisticated vocabulary for

obesity and locations of

specific fat deposits: cotztzotzol--soft, drooping fat and skin deposited

along the calf; eltzotzolli--flabby, fatty tissue and skin deposited

across

the chest; ititzotzolli--soft, bland fat and skin in the hypogastrium

region;

puchquiyot| very flabby fat widely distributed over the body; and

quechtzotzol--a flabby, double chin (Lopez Austin, 1988, p. 259).

They also had a well-recognized understanding

of infant malnutrition and the

concept of kwashiorkor. The nursing child of an Aztec mother who became

pregnant was called tzipitl. Both child and fetus were perceived as

"interlaced" with the mother and former breast-fed infants,

deposed by the

birth of a second child, were perceived as weak, slow to develop and

characterized by diarrhea and weight loss that precipitated emaciation

and

death (Lopez Austin, 1988, pp. 268-269).

One Aztec manuscript, the Codice Vatican Latino

Number 3738, depicts the

poignant result of kwashiorkor and untimely infant death. In the Aztec

belief

system breastfeeding children who died were miraculously transported

to the

nether-world, to a site called Chichihualcuauhco (alternative spelling

Tonacacuahtitlan or Xochatlapan), where the infants played under magical

trees

that bore fruits in the shape of human breasts. There, under the protective

branches and fruits of the magical tree, the infants flourished; when

hungry,

they merely tilted their tiny heads upward to receive sustenance, human

milk

dripping from the magical breast fruits.

Ortiz de Montellano (1990) collected extensive

Aztec references to dental

disease. Caries were thought caused by human behavior, especially incautious

exposure to sudden temperature change. Suffering patients were told

to avoid

thermally warm foods and were instructed how to avoid dental decay using

an

allopathic, "hot-cold' approach that stated:

Wait between consuming warm things [and between

eating] have a [thermally]

cold drink; avoid chewing green maize stalks [classified as 'cold']

at night.

Given the sugary properties of maize stalk pith,

ancient Aztec recommendations

logically reduced exposure to "sticky" foods and probably

lowered the

incidence of dental caries.

Aztec physicians also perceived associations

between drinking cold water,

eating raw vegetables and diarrhea. Gout, identified as a "cold"

disease, was

thought to be caused by undue exposure to cold wind and treated by ingesting

hallucinogenic plants [not specified] or by eating tobacco leaf.

Given the meticulous research by these eminent

Mexican researchers, it is

interesting that documentation is lacking in ancient Mexico for other

types of

malnutrition. Katz et al. (1974) concluded, however, that rickets would

not be

a concern in

Aztec society where the dietary staple of maize

tortillas previously treated

with lime was coupled with human exposure to the sun. Given, too, that

traditional Aztec diet was balanced and based upon a combination of

maize and

beans with complementary amino acids, the presence of pellagra also

would have

been unlikely (Grivetti, 1992).

HUMAN TRAGEDY: THE EPIDEMIC ERA (1520-1581)

The conquest of Mexico by the Spanish and the

blending of Old and New World

civilizations, produced an enormous legacy with both positive and negative

effects. Among the positive effects of cultural contact were dramatic

medical

and dietary exchanges, whereby the foods of Africa, Asia and Europe

were

introduced to the Americas. Old World foods introduced to Mexico within

the

first 100 years of Spanish contact included: almond, apples, apricots,

cabbage, cattle (whether beef, milk, or dairy products), garlic, lemons,

lettuce, olives, oranges, pig (whether pork or lard), rice, sheep (including

lamb, milk, and dairy products), sugar cane and wheat.

New World contributions to Old World cuisine

also were positive and included

an enormous range of foods readily adopted throughout Africa, Asia and

Europe.

Among them were artichokes, avocados, kidney beans, cacao (chocolate),

cassava, chile peppers, guava, maize, papaya, peanuts, pineapples, pumpkins,

sunflower, tomatoes and turkey.

Agricultural and dietary exchanges represent

the positive side of culture

contact; the mirror image, unfortunately, was terrible, unplanned and

difficult to imagine. Old and New World medicine, both rounded upon

prescientific concepts of allopathy and the signature of opposites (contraria

contraris), could not prevent or stem unintended outbreaks of communicable

disease and widespread epidemics. Specific chronicles detailing the

origins,

spread and outcome of the diseases exist, but no one counted or documented

the

names of the millions who died.

The first 60 years of Spanish occupation in Mexico

were defined by four

epidemics characterized by medical symptoms not previously seen or experienced

in the New World. Smallpox caused the first epidemic of 1520 to 1521

and

struck during the second year after Spanish contact. Previously unknown

to the

New World, it was called hueyzahuatl by Aztec physicians. Aztec medicine

could

not stop its spread, and untold thousands died. The second epidemic,

also

smallpox (possibly in combination with measles?) occurred 10 years later

in

1531. In Aztec accounts it was known as tepiton zahuatl or "little

leprosy."

The third epidemic erupted in 1545 and lasted 3 years. The cause of

this

outbreak is unknown and its symptomology cannot be identified; the Aztecs

called it cocoliztli. By some estimates onethird of the pre-Spanish

population

of Mexico died as a result of these first three epidemics. A fourth

and last

major epidemic hammered the Native American population; it lasted for

5 years

from 1576 to 1581. This disaster was also called cocoliztli; it reportedly

killed an additional 300,000 to 400,000 Native Americans in New Spain

(Risse,

1987, p. 27).

From the vantage point of 1992 such a human disaster

seems impossible. The

evidence, however, is undeniable. How many people died? No one knows

with

certainty. The power of words left by educated, literate ancient Aztec

men and

women who lived during those times cut through time and demand our attention.

They are as poignant now as when first transcribed more than 100 years

ago by

Brinton:

Zan tlaocolxochitl, tlaocolcuicatl on mania Mexico

nican ha in Tlatilolco, in

yece ye oncan on neiximachoyan, ohuaya. (Only sad flowers, sad songs,

are here

in Mexico, in Tlatilolco, in this place these alone are known, alas.)

Zan ye

chocaya amaxtecatl aya caye chocaya tequantepehua. (He who cared for

books

wept, he wept for the beginning of the destruction,) (Brinton, 1890,

pp. 82-83

and 122-123).

BLENDED TRADITIONS: AZTEC AND SPANISH "HOT-COLD" IN THE 20th CENTURY

Spanish allopathic medicine and "hot-cold"

were brought to the New World where

the Mediterranean pattern blended with existing Aztec and subsequent

Maya,

Inca and other Native American medical practices. Ultimately, the Spanish,

Mediterranean allopathic system dominated, then later paralleled and

complemented allopathic practices introduced to the Americas by British

and

French physicians. The Spanish allopathic legacy flourished within Mexico,

then extended southward throughout Central and South America. The Spanish

pattern also diffused northward into regions that encompassed the southwestern

portions of the United States of America.

This ancient Spanish legacy was spread throughout

the American southwest and

California by Spanish priests, especially Jesuits and the Franciscans,

and is

expressed in American-Hispanic food practices today. But while the practices

exist widely within the ethnic Hispanic population of the Americas and

the

Caribbean the patterns are highly variable and cannot be reduced to

simplistic

summaries.(6)

Wide variation in "hot-cold" designations

is acknowledged by researchers, but

the extent of variation has troubled some authors who have concluded

there is

little value in summarizing and comparing data from different Hispanic

respondents from widely separated geographical localities. Such variation,

however, should be a challenge rather than a frustration, and examination

of

intercultural variation presents a valuable lesson, Just as people are

not

alike and groups are dissimilar, it is logical that the expression of

traditional medicine and nutritional practices should be highly variable,

Data

from nine representative publications are summarized here to demonstrate

variation and range of allopathic, 'hotcold" practices within Hispanic

cultures of the Americas.

Madsen (1955) identified a continuum of five

terms for "hot-cold" used in

Mexico, a pattern also balanced by degree of food freshness: very hot

(muy

caliente), hot (caliente), temperate-neutral (templado), cold (frio)

and very

cold (muy .frio), set within designations of very fresh (muy fresco)

and fresh

(fresco). Madsen sought explanations for "hot-cold" designations

and found

that many species grown in very wet ground were classified "cold,"

but since

their leaves and fruits were exposed to the sun the "cold"

was diluted,

whereupon such foods were designated "fresh" or "very

fresh." She concluded

that food characteristics of color, spiciness and ecological habitat

influenced category assignment. Madsen also found that 'hot-cold"

designations

extended beyond food to human activities and commercial medicines, Movies

screened locally were classified "cold," while Alka Seltzer,

a medicine

manufactured in the United States, was designated "fresh.' She

prepared

extensive food lists for "hot-cold' that formed a baseline for

comparison

against Hispanic practices elsewhere in North, Central, South America

and the

Caribbean.

Logan (1972, 1977) conducted work in Mexico and

argued nearly 20 years ago

that Hispanic allopathy and "hot-cold" practices predated

Spanish conquest. He

urged scientifically trained nutritionists and dietitians to consider

"hot-cold" food assignments, then challenged nutrition educators

to implement

dietary information using an allopathic framework more easily understood

by

Hispanic clients. Logan noted that Mexican farmers recovering from illness

traditionally snacked on peanuts, and he urged nutrition educators to

examine

other components of traditional Hispanic medicine, and to identify common

practices that promoted sound diet, nutrition and health. He was among

the

first to suggest that pellagra may not have existed in pre-Columbian

Mexico

because of balanced Aztec dietary practices that blended maize and legumes.

Logan posed the tantalizing hypothesis that outbreaks

of pellagra throughout

the Americas during the 19th and 20th century occurred at locations

where

allopathic "hotcold" practices had been forgotten or abandoned.

Suarez (1974) worked among Native Americans in

the Venezuelan Andes and

identified a classical Spanish, Mediterranean allopathic, 'hot-cold"

system,

set within precontact indigenous medical practices. She identified disease

categories with specific gender assignments thought to be caused by

unsatisfied food cravings: mal de madre (diseases of mature women who

previously had conceived), maldijada (diseases of mature women who never

had

conceived) and padrejon (diseases of mature men). Suarez identified

other

disease categories, among them: arco (illness produced by rainbows),

mal de

ojo (evil eye disorders), mal viento (sickness after exposure to draft),

mojan

(witchcraft) and pasmo (sickness after exposure to cold water).

Molony (1975) examined variation and consistency

in Hispanic "hot-cold"

beliefs. "Cold" designations commonly were linked with an

ecological water

niche, i.e., edible plants and animals that lived in or grew near water.

"Hot'

foods commonly were items associated with sunlight, or were consumables

that

burned the lips or mouth, hence "hot" designations for ice

and distilled

alcohol. She found that cuts of meat obtained from male animals were

sometimes, but not always, identified "hotter" than those

from a female of the

same species. Molony also studied combination dishes and wrote how cooking

altered "hot-cold" designations. She reported that when foods

were combined or

cooked with spices, such dishes usually were designated "hot,'

while food

combinations boiled or cooked in water or other fluids usually were

"cold.'

Mathews (1983) wrote that while Hispanics practiced

a classical Mediterranean

"hot-cold" tradition, foods often were categorized along four

additional

continuums: dangerous-safe, raw-cooked, healthyunhealthy and sexual

promotingsexual neutralizing. He noted the common extension of "hot-cold"

designations to disease potential and sexual activity: "hot"

people (male or

female) supposedly suffered more "cold" illness and exhibited

strong sexual

drive, whereas "cold" individuals suffered more "hot"

medical conditions and

frequently failed to marry or produce children. Mathews reported how

foods

were used and diets planned to neutralize or balance human conditions.

"Hot"

people were encouraged to eat more beans (white varieties), cucumbers,

eggs

(duck), fish-bone powder and gelatin, whereas "cold" people

were prescribed

more chiles, garlic, onions and shrimp.

Mathews' most important contribution, however,

was his caution against

preparing master lists of "hot-cold" foods for widespread

nutritional

counseling (Table 3). The problem he identified, called "intercultural

variation" by social scientists, showed the difficulty of relying

upon food

surveys and "hotcold' designations. Mathews wrote that "hot-cold"

existed

widely within Hispanic culture, but designations received from residents

of a

region, a village or even a single household varied widely. He documented,

furthermore, that the same respondent might provide different food assignment

categories during different times of the day and that responses were

apt to

change during different seasons, even through the years.

In an attempt to examine response consistency

for allopathic, "hot-cold"

category assignments, Mathews interviewed adult men and women (n= 40)

in the

village of Oaxaca, Mexico, and sought information on 88 local foods.

Category

consistency was met when respondents agreed 100 to 75% of the time;

inconsistency was considered less than 75% agreement (Table 4). Within

the

village some foods consistently were designated "hot,' such as

chilies, mescal

(distilled liquor prepared from maguey), black mole sauce (a combination

of

chile and chocolate), onions, salt, chocolate and garlic. Greatest village

agreement for "cold" foods was seen with water, tejate (beverage

of corn meal

and chocolate), vegetable soup, rice water, rice, estofado (green tomato

sauce) and cheese. Least agreement (i.e., strongest inconsistency) was

associated with seven common foods: camomile, coconut, cucumber, edible

grasshoppers, potatoes, raisins and tea.

The anthropologist George Foster (1984, 1985)

studied the Mexican village of

Tzintzuntzan and reported that "Western" and traditional medicine

existed side

by side, where concepts of magic and evil eye (mal de ojo) were followed

along

with reasonable dietary practices and "hot-cold ""assignments.

Foster found

extensive evidence for allopathic practices in Tzintzuntzan. He wrote

that

fever was "extracted" by bathing, by cupping (bleeding) and

by administration

of purgatives or compounds to induce sweating. Body chills, in contrast,

are

neutralized by ingesting appropriate "hot" foods and herbal

teas. Dietary

"balance" and management of "hotcold" illness were

facilitated by selecting

from five distinctive beverage categories: 1) te: brews of a single

herb,

either "hot' or "cold" depending upon the illness to

be treated, previously

soaked or boiled in water, then drunk thermally hot, 2) cocimiento:

two or

more "hot" or "cold' herbs boiled together, drunk thermally

hot, but sometimes

cooled and stored before drinking, 3) horchata: seeds of melon and watermelon,

designated "cold," then ground, soaked in water, and drunk

to cool the kidneys

or stomach and used to counter diarrhea or constipation, 4) care: toasted

seeds of avocado or mango, classified "hot," then ground and

boiled or soaked

in hot water, and 5) agua de uso: miscellaneous herbs, usually "cold,"

boiled,

cooled, then drunk throughout the day as a thirst-quenching beverage.

According to Foster the allopathic, dietary system

of Tzintzuntzan consisted

of the classic Mediterranean triad: hot, neutral and cold. "Cold"

diseases,

among them pneumonia, sore throat, stomach ache and tonsillitis, were

treated

by eating representative "hot" foods such as distilled alcoholic

beverages,

avocado, beans, chocolate, coffee, garlic, honey, peanuts, pork, brown

sugar,

rue, wheat tortillas and water. "Hot" diseases, among them

diarrhea, smallpox,

and sunstroke, were mitigated or cured using "cold" foods

such as iced

beverages, cauliflower, carrots, chicken eggs, fish, ice cream, lamb,

lard,

lime, mallow, papaya, pineapple, salt, squash, turkey, vinegar and watermelon.

Examples of neutral-temperate foods at Tzintzuntzan included beer, bread,

chicken, maize and maize tortillas. Foster noted that most over-thecounter

oral medicines (e.g., aspirin) were classified "hot." In addition,

his

respondents also classified foods along a 'heavy-light" continuum.

So-called

"heavy" foods included eggs, most meats, milk, potatoes and

rice. "Heavy"

foods were considered especially dangerous and unhealthy if eaten at

morning

or evening meals, but their assignment shifted along the continuum toward

"lighter" if eaten at the midday meal.

Tedlock (1987) worked in Guatemala where he found

a continuum of eight

'hot-cold" terms: fiery hot, very hot, hot, warm, lukewarm, cool,

cold and

very

cold. He noted that most "warm" foods

were astringent, bitter or dark-colored,

whereas "cool' consumables frequently were light-colored, Tedlock

discovered

that respondents made no specific attempt to balance dietary components

of a

meal along "hot-cold' lines, as would be expected in a classical

Mediterranean

system, but instead formed socalled "healthy meals" that combined

"warm' foods

such as black or red beans, beef, dried chili, cinnamon, cloves, coffee,

duck,

garlic, ginger, yellow maize, peppermint and brown sugar, with "lukewarm"

items, identified as cheese, leafy greens, noodles, potatoes, rice,

sauces

made from fresh chilies, tortillas or watercress. Tedlock wrote that

'hot-cold' assignments along the continuum were widely inconsistent

from town

to town within the same geographical region, and highly variable from

person

to person within the same village. Some respondents changed their minds

and

offered different assignments when interviewed at different times of

the same

day.

DECLINE OF ALLOPATHY: RISE OF THE GERM THEORY

Less than 150 years ago concepts of disease and

illness transmission in the

United States of America were primarily allopathic and based upon the

"hot-cold' balance. The allopathic approach to medicine, however,

was

challenged after the discovery of fermentation principles and publications

on

anthrax by Louis Pasteur in 1877, Afterwards, the concept of "germ

theory"

began to be accepted widely, and allopathy declined. While physicians

were

attracted to the germ theory, the general public did not take easily

to this

explanation for disease and disease transmission. Furthermore, the new

approach raised doubts and fears that since "germs were everywhere

and must

cover everything," fresh or prepared foods sold in stores and open-air

markets

were potentially dangerous to consumers.

Kramer (1948) documented this debate and the

public doubts that followed in

the decades after Pasteur's discoveries. In a wonderful, but frequently

overlooked essay, he noted that the fledgling field of microbiology

flourished

only after 1880 when scientists discovered specific organisms for diseases

such as cholera, diphtheria, pneumonia, tetanus, tuberculosis and typhoid.

He

observed that by 1890 microscopes no longer were technical "oddities,"

but had

become standard university equipment. However, millions of people worldwide

still did not accept the germ theory, because they believed their eyes

rather

than the microscopic world.

Gradually there was widespread acceptance in

Western medicine of the germ

theory and disease causation, With acceptance there were two results.

First,

allopathy and use of "hot-cold" concepts declined, and second,

scientific

arrogance began to develop. As the Western medical model advanced, allopathy

and humoral medicine were discounted, then ignored and finally abandoned

in

many parts of the world. As science progressed, allopathy retreated,

lingering

in non-Western, so-called 'quaint' regions of the world, geographical

areas

considered by some scientists to be less advanced.

As the gap between science and allopathy widened,

many scientists lost the

fine art of communication. Some scientists cared about the health and

nutritional status of different peoples and regions of the world, and

for the

medical-dietary practices of American immigrant groups. Because they

were

trained in science, however, most physicians and nutritionists saw little

reason to identify and understand nonscientific approaches to health

and diet

practiced by their ethnic clients. Was it not easier, and perhaps better

to

treat nutritional conditions such as diabetes, diarrhea, obesity and

vitamin

and mineral deficiencies using "standard diets"? Most textbooks

on clinical

and dietary approaches to treatment noted that the easiest way to communicate

with clients and treat nutrition-related disorders was to assemble clients

or

bring them to central localities, where lectures could be prepared and

delivered to the greatest number, with the least cost in time. Nutrition

education was easy and had entered a new age.

But a problem remained: while sound, scientific

lectures were delivered and

"standard diets' distributed, communication between clients and

health-nutritional professionals declined. Clients were eager for nutrition

and dietary information, but the information they received was of limited

use.

Nutrition educators, in turn, were eager to provide facts that would

facilitate treatment, but the information they provided was of limited

use.

Nutrition counseling frequently became a dialogue of the deaf, where

many

words were spoken and many smiles exchanged, but instead of winning

and

overcoming disease and malnutrition, education was a casualty of the

process.

Health and nutrition professionals frequently could not communicate

scientific

principles to clients who did not believe in the germ theory and were

distrustful of science. As a result both sides have been frustrated,

A 1992 PERSPECTIVE

Allopathy flourishes throughout the United States

of America in 1992 as a

medical-nutritional approach. Most Americans practiced allopathy before

1885,

some still do. It is not scientific, but it is not necessarily nonsense.

Allopathy is practiced from California to Maine; it thrives along our

coasts

and exists within the heartland of America.

Throughout this four-part series we have explored

the origins, distribution

and comparative aspects of allopathy, a prescientific approach to medicine,

nutrition and food practices. Part One documented that allopathy and

"hotcold"

concepts originated in ancient India and were manifest in the pioneering

medical texts of Caraka, the father of medicine. Part Two examined the

spread

of allopathy and "hot-cold practices westward from India into the

Mediterranean region, where they were adopted by ancient Greek and subsequent

Roman, then Christian, Jewish and Muslim Physicians. Part Three explored

the

diffusion of allopathy eastward from India into China, and examined

the

complexities of the Yang-Yin, "hot-cold" healing system of

eastern Asia. The

present and concluding article in this series has traced the spread

of

Mediterranean allopathic, "hot-cold" practices into Central

America where they

blended with indigenous, preColumbian Aztec medical-dietary traditions

that

existed long before the arrival of Columbus in the Caribbean and subsequent

conquest of Mexico by Hernando Cortes.

In the United States of America allopathy and

scientific approaches to

medicine, nutrition and diet exist side by side. Americans are not a

homogeneous people who all believe in science. Nutrition educators,

dietitians

and university professors, encounter cultural diversity and scientific

skepticism daily. During the past 500 years cultural, religious diversity

has

enriched the American continents; peoples from all inhabited world regions

now

live in this land along with Native Americans who were here before European

contact. Many citizens have well developed attitudes, beliefs, and practices

regarding health, diet and nutrition. Some of these practices are

scientifically sound; others are nonsense. Some allopathic principles

identified in this series are sound and complement scientific knowledge.

As

dietary and nutritional counselors we face a basic challenge: how to

provide

correct, informative, high-quality nutritional information to the most

clients, with the least cost in terms of money, time and effort.

The general public, however, is eager to learn

and we professionals are eager

to teach. Having worked on cultural practices and food habits for more

than 25

years I have experienced individuals of four types within the United

States.

The first has no knowledge of allopathy or "hot-cold" concepts,

although they

originate from a population that traditionally has practiced it. The

second

will have a vague to excellent recollection of such medical-dietary

systems,

but prefer to receive nutrition information within a scientific context.

Other

individuals primarily will follow allopathy and "hot-cold"

practices, then use

these concepts interchangeably with scientific medical-nutritional information

provided. The fourth type of person, a minority, seeks nutrition information

and is eager to learn, but rejects scientific explanations and the germ

theory. Such clients base their medical and dietary principles primarily

upon

"hotcold" concepts; often they are the most needy, and often

they are the most

challenging. How we communicate with ethnic Americans is a measure of

our

educational skills and talents. It is obvious that not all Asians or

all

Hispanics are the same. Too often, nutrition educators lump Asians and

Hispanics into single groups and seek common food practices that would

make

counseling easier. Not all Asian-Americans eat rice; not all

Hispanic-Americans eat tacos; not all Italian-Americans eat spaghetti.

One

pattern of dietary advice and nutritional counseling is not suitable

to all.

Diversity remains our national strength, but with diversity comes complexity

and the need to explain scientific concepts using culturally correct

examples

that are easily understood. If you agree that this is our professional

challenge, not our mutual frustration, then this series has been successful.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Arano LC [Translator]. Tacuinum Sanitatis. The

medieval health handbook. New

York: George Braziller, 1976.

Bernal Diaz del Castillo. The discovery/conquest

of Mexico. 1517-1521.

Translated by AP Maudslay. New York: Grove Press, 1956.

Bravo F [1570]. Opera medicinalia. London: Dawson, 1970.

Brinton DG [1890]. Ancient Nahuatl poetry, containing

the Nahuatl text of

XXVII ancient mexican poems. Brinton's Library of Aboriginal American

Literature. Number 7. New York: AMS Press, 1969.

Carter G. Pre-Columbian chickens in America.

In: Man across the sea: problems

of pre-Columbian contacts. CL Riley, ed. Austin: University of Texas

Press.

1971:178-218.

Clark M. Health in the Mexican-American culture.

Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1959.

Currier RL. The hot-cold syndrome and symbolic

balance in Mexican and

Spanish-American folk medicine. Ethnology 1966;5:251-63.

de la Cruz M [1552]. The Badianus Manuscript

(Codex Barberini, Latin 241)

Vatican Library. An Aztec herbal of 155L Translated by EW Emroart. Baltimore:

The Johns Hopkins Press, 1940.

Farfan A [1579; 1592]. Tractado breve de medicina.

Madrid: Ediciones Cultura

Hispanica, 1944.

Foster GM. How to stay well in Tzintzuntzan, Soc Sci Med 1944;5:523-33.

Foster GM. How to get well in Tzintzuntzan. Soc Sci Med 1985;7:807-18.

Gillies HC. Regimen Sanitatis. The rule of health.

A Gaelic medical manuscript

of the early sixteenth century or perhaps older, from the Vade Mecum

of the

famous Macbeaths, physicians to the Lords of the Isles and the Kings

of

Scotland for several centuries. Glasgow: Robert Maclehose, 1911.

Grivetti L. Nutrition past--nutrition today.

Prescientific origins of

nutrition dietetics. Part l. Legacy of India. Nutr Today 1991a;26(1):13-24.

Grivetti L. Nutrition past--nutrition today.

Prescientific origins of

nutrition dietetics. Part 2. Legacy of the Mediterranean. Nutr Today

1991b;26(4):18-29.

Grivetti L. Nutrition past--nutrition today.

Prescientific origins of

nutrition dietetics. ['art 3. Legacy of China. Nutr Today 1991c;26(6):6-17.

Grivetti L. Clash of cuisine. Nutr Today 1992;27(2):13-15.

Harrington J [1607]. The school of Salernum.

Regimen Sanitatis Salemi. Rome:

Saturnia Editions, 1957.

Hernandez F [1577]. Historia de las plantas de

la Nueva Espana. 1. Ochoterena,

ed. Mexico City: Imprenta Universitaria, 1942, 3 vols.

Ingham JM. On Mexican folk medicine. Am Anthropoloogist. 1970;72:76-87.

Jarcho S. Medicine in sixteenth century New Spain

as illustrated by the

writings of Bravo, Farfan, and Vatgas Machuca. Bull History Med 1957;

31:425-41.

Jett S. Precolumbian transoceanic contacts. In

Cyr DL, ed. The Diffusion

Issue.Santa Barbara, CA: Stonehenge Viewpoint, 1991:21-50.

Johannsen CL, Parker AZ. Maize ears sculptured

in 12th and 13th century A.D.

India as indicators of pre-Columbian diffusion. Econ Botany 1989;43:164-80.

Katz SH, Hediger ML, Valleroy LA. Traditional

maize processing techniques in

the New World. Science 1974;184:765-73.

Kay M, Yoder M. Hot and cold in women's ethnotherapeutics.

The

American-Mexican West. Soc Sci Med 1987;25:347-55.

Kramer HD. The germ theory and the early public

health program in the United

States. Bull History Med 1948;22:233-47.

Lloyd CER. Right and left in Greek philosophy. J Hellenic Stud 1962;82:56-66.

Lloyd CER. The hot and the cold, the dry and

the wet in Greek philosophy. J

Hellenic Stud 1964; 84:92-106.

Logan MH. Humoral folk medicine. A potential

aid in controlling pellagra in

Mexico. Ethnomedizin 1972;1:397-410.

Logan MH. Anthropological research on the hotcold

theory of disease. Some

methodologica] suggestions. Med Anthropol 1977;1(4):87-112.

Lopez AA. The human body ideology. Concepts of

the ancient Nahuas. Translated

by T Ortiz de Montellano B, Ortiz de Montellano. Salt Lake City: University

of

Utah Press, 1988, vol 1.

Madsen W. Hot arid cold in the Universe of San

Francisco Tecospa, Valley of

Mexico. J Am Folklore 1955;68:123-39.

Mathews HF. Context-specific variation in humoral

classification. Am

Anthropologist 1983;85: 826-47.

Messer E. The hot and cold in Mesoamerican indigenous

and hispanicized

thought. Soc Sci Med 1983;4:339 46.

Molony CH. Systematic valence coding of Mexican

"hot" "cold" food. Ecol Food

Nutr 1975;4:67-74.

Ortiz de Montellano BR. Aztec medicine, health,

nutrition. London: Rutgers

University Press, 1990.

Peredo MG. Medical practices .in ancient America.

Practicas medicals en la

America antigua. Mexico City: Ediciones Euroamericanas, 1985.

Risse GB. Medicine in New Spain. ln RL Numbers,

ed. Medicine in the New World.

New Spain, New France, New England. Knoxville: University of Tennessee

Press,

1987:12-63.

Sahagun B de. The war of conquest. How it was

waged here in Mexico. The

Aztecs' own story as given to Ft. Bernardino de Sahagun. Rendered into

Modern

English by AJO Anderson and CE Dibble. Salt Lake City: University of

Utah

Press, 1978.

Suarez MM. Etiology, hunger, and folk diseases

in the Venezuelan Andes. J

Anthropol Res 1974:30:41-54.

Tedlock B. An interpretive solution to the problem

of humoral medicine in

Latin America. Soc Sci Med 1987;24:1069-83.

Vargas LA. Food ideology and medicine in Mexico.

In White PL, Selvey N, eds.

Malnutrition. Determinants and consequences, Proceedings of the Western

Hemisphere Nutrition Congress VII, Miami Beach, Aug 7-11, 1983. New

York: Alan

R. Liss, 1984:423-9.

Williams CD. A nutritional disease of childhood

associated with a maize diet.

Arch Dis Child 1933;8:423-33.

(1) Spread of allopathic medicine and hot-cold

designations into the British

isles originated with Roman contact. A 16th century Gaelic allopathic,

hot-cold medicine text, Regimen Sanitatis, has been published by

Gillies(1911).

(2) Geographers, among them Carter (1971), Jett

(1989) and Johannsen and

Parker (1989), have urged reconsideration of the traditional view that

Europeans were the first to encounter Native Americans, They argue that

New

World maize existed in Asia before 1492, and they have documented the

presence

of Asian chickens in he New World before the arrival of Columbus.

(3) A strong dietary prohibition towards fish

remains today thoughout Indian

populations of the central valley of Mexico.

(4) English designation-equivalent uncertain.

(5) The term kwashiorkor is used by the Ga people

of Ghana to designate a

disease "the-first-child-gets-when-the-second-child-is born."

It was brought

into the Western medical literature by Cecile Williams(1933)

(6) Representative references to Hispanic hot-cold

literature not cited in

this review may be obtained upon request from the editor.

Dr. Grivetti is Professor of Geography and Professor

of Nutrition at the

University of California, Davis campus. His research focuses on human

dietary

patterns, using historical and contemporary perspectives, especially

among

African, Mediterranean societies and ethnic populations in the United

States.

He is coauthor with W.J. Darby and P. Ghalioungui of the awardwinning

book.'

Food. The Gift of Osiris New York: Academic Press, 1979).

-- End --

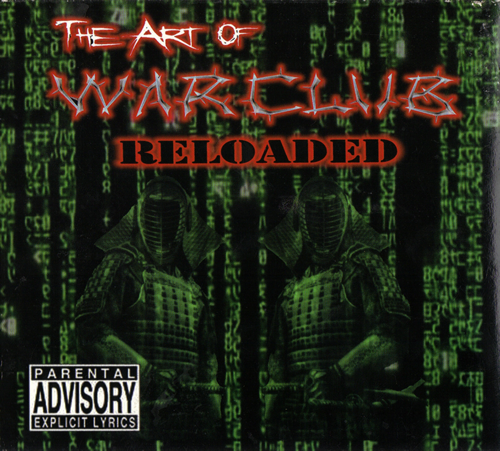

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06