Journal of the Southwest, Winter 2000 v42 i4 p897

Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult. SUSAN E.

JAMES.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2000 University of Arizona

The origins of the kachina cult of the Southwest have been, and continue to be, a matter of some debate. Theories abound. Some perceive the cult growing in a cocoon of isolation among the aggregated prehistoric pueblos of the Little Colorado and Rio Grande river valleys during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (Mathien and McGuire 1986; Bradley 1993; Plog 1993) or even as late as the seventeenth centuries (Fewkes 1898). Another theory (later modified) proposes that the kachina cult arose in imitation of post-Columbian Spanish Catholicism (Parsons 1933; White 1934: 626-28). Some who object to the theory of isolated development maintain that the cult was imported whole from the valley of Mexico, possibly as a corollary of pochteca economic colonization (Hibben 1967; Kelley 1966; Reyman 1978: 242-59). Some acknowledge similarities between the beliefs and religious rituals of pre-Columbian peoples in the Southwest and Mesoamerica but attribute these to a complex cosmology of ideas held in common by disparate peoples remote from each other in time or in geography (Brody 1977). This theory discounts historical interaction among peoples to explain such a commonality of beliefs. The logical conclusion, therefore, of such a theory is the presupposition of a shared belief system originating in an undefined protean homeland whose inhabitants, during their ancient migrations to the Americas, carried such belief systems intact through successive waves of relocation that spanned not only distance but a period of time measured in millenia.

Recent investigation in the field has uncovered a wealth of complex connections over time between the American Southwest and the Mesoamerican cultures to the south.(1) Archaeological evidence such as ballcourts implies importation into the Southwest of religious ideas originating in Mexico and further south. However, existing today in the Hopi kachina cult would appear to be living evidence of this penetration. The purpose of this paper is to discuss one facet of that complex interaction which seems to point to a more intense impact on the Southwest by religious ideas coining from Mesoamerica than has perhaps been appreciated. A brief outline of these cultural contacts is needed to set the subsequent discussion of parallel elements between the Aztec religion(2) and the Hopi kachina cult in context.

CULTURAL CONTACTS BETWEEN THE SOUTHWEST AND MESOAMERICA

Haury (1974:95-96) has set out a schema for cultural exchange between north and south over a considerable period of time which illustrates a pattern of interaction focusing on the Hohokam as cultural mediator. This schema extends from the adoption of maize agriculture by the peoples of the Southwest at the beginning of the Common Era, through the importation of exotic trade goods such as iron pyrite mirrors, copper bells, and macaw feathers at the end of the Classic Period and into the Post-Classic, a thousand years later. Trade in this later period, however, ran in both directions, with turquoise (Weigand & Harbottle 1993: 159-177), buffalo hides, turkey farming (Breitburg 1993), irrigation engineering technology (Doolittle 1993: 131-151), and sea shells (Bradley 1993:121-151) as proven commodities or technologies transferred from north to south. The routes that connected the various, and fluctuating, cultures of Di Peso's Gran Chicimeca (to use a controversial term) and the cultures of the Valley of Mexico seem to have been concentrated between the coast of western Mexico and the Sierra Madre Occidental. Braniff Cornejo (1993: 65-82) has done an excellent job of delineating several of these principal routes while Altschul (1997: 57-69), Lopez (1997: Chapter 5), and Doelle & Wallace (1997: 71-84) indicate how the San Pedro River valley, a natural corridor, developed as a cultural north-south threshold between geographically separate peoples from about 700 to 1450. Other geographic corridors and cultural thresholds existed whose importance is just now being recognized (Carpenter 1997: 113-127; McGuire 1993: 95-119; Riley & Manson 1991: 141).

This increasingly perceived complexity with regard to north-south cultural interaction is quantifiably measurable if one sticks to pottery shards, architectural engineering, or the number of beveled turquoise tesserae found at a given site. One is on distinctly less solid ground moving into the area of such intangibles as the processing of new ideas, the adoption of religious ritual, or the acceptance of particular world views to explain external phenomena. Yet even here, certain consistent models of human behavior must hold true. The wholesale adoption of such culture changing plants as corn, cotton, and to a lesser degree, beans and squash, presupposes an adoption of the planting and propagation rituals which must necessarily have gone with them (Beals 1974: 61; Braniff Cornejo 1993: 68; Kelley 1997: 238). According to Parsons (1939: 1027 note): "The music of the corn-grinding songs of western Keres is notably Pima in character, suggesting that grinding songs traveled north with maize." The appearance of ballcourts as far north as Wupatki in northern Arizona, of raised mound architecture in the San Pedro River valley, of the development of the turquoise trade, the "cash crop" of the Southwest, all carry with them the implication of ritual interchange and religious adaptation (Weigand & Harbottle 1993:171). The shared use of a common linguistic family, such as the Uto-Aztecan between the Aztec and the Hopi, would have facilitated such exchanges and adaptations.(3)

The diffusion of, and more importantly the acceptance of, specific rites and concepts moving into the American Southwest from Mexico which led directly to the development of the kachina cult occurred over a period of approximately two hundred years (roughly 1250-1470 AD), a time marked by extreme drought and subsequent population displacement on the Colorado Plateau (Altschul 1997:64; Adams and Hull 1980:14; Frazier 1986:203-7; Adams 1991:142). The insecurities of life caused by these natural disasters created unstable and newly merged social groups desperate for ways to integrate their uprooted cultures without the untenable strain of warfare, and equally desperate for new religious strategies to propitiate suddenly indifferent gods (Schaafsma & Schaafsma 1974: 535ff). Altschul (1997: 67) has described radical cultural shifts in finite time, as demonstrated by architectural changes in the San Pedro River valley, while Doelle (1997:79-81) has pointed to the dynamics of change through population migration in the mid-thirteenth century in this same area. Both findings, as well as those of Doyel (1993: 61) and Braniff Cornejo (1993:66), support the notion of cultural flux in the Southwest that occurred as a result of traumatic alterations in the climate. As McGuire (1993: 109) points out:

The Classic period brings major changes in the

spatial distribution and

intensity of exchange in southern Arizona. These changes occur at all

levels from Mesoamerican contacts to local patterns of exchange. In

both

the Soho and Civano phases, the Phoenix Basin seems to have had less

access

to Mesoamerican contacts than Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico, but

does

appear to be participating in a system of exchange and symbols that

crosscuts the entire Southwest.

The arrival of new religious strategies, probably filtered by the population

groups through which they had passed, coincided in the Southwest with

this social sense of dislocation, with threats from natural and supernatural

forces, and carried with them the dual promise of social cohesion and

rain (Fewkes 1924: 389,397). Cutting across clan lines and acting as

an integrating factor in a usually polarized society (Adams 1991:143),

the kachina cult was the glue that held together the disparate cultures

of peoples who had recently joined in new combinations in the name of

survival (Riley 1988:211; Adams 1991:145). Equally, the cult offered

a pantheon of deities and a schedule of rituals whose primary and reputedly

successful purpose was to bring rain. It is no wonder then that these

southern ideas were eagerly incorporated by the peoples of the Southwest

into existing ritual schedules, thus forming the genesis of today's

kachina cult (Spicer 1986, 26).

THE HOPI TRADITION

The Hopi tradition following the Spanish entrada is unique among Southwest pueblo groups. During the Pueblo Revolt against the Spanish in 1680, the Hopi dispatched the Spaniards resident among them, and they alone among the pueblos managed to keep the Spanish out permanently. This violent rejection of a violent invasion and the ideas represented by the invaders is an anomaly in Hopi history for their tradition has been characterized by a willingness to accept new ideas, agricultural and religious, where those ideas were proven effective. Recorded examples among the Hopi of this syncretic dynamic of incorporating foreign groups and their religious rites into existing domestic religious practices are legion. During the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, Tiwa refugees from Nafiat/Sandia built the village of Payupki on Second Mesa, and Tano refugees still live in Hano village on First Mesa. These have added their own kachinas (Colton 1959; Wright 1977: 84) and interpretive rituals to the melting pot of the kachina cult, as have immigrants, visitors, or reacculturating Hopi from Zuni, Acoma, Tiwa (K'hapoo/Santa Clara), Towa (Walatow/Jemez), and Havasupai (Fewkes 1898; Fewkes 1922; Teiwes 1991: Plate 17).

After the sack of the renegade Hopi village of Awatobi by other Hopi about 1700, Awatobi women and a few men who knew certain rituals and songs, principally those intended to bring rain, were saved from the general massacre if they agreed to teach their knowledge to the invaders (Fewkes 1893: 366; Fewkes 1924: 395). This recognition of the value of and acceptance of new religious knowledge, conditional to proofs before the people, is still imitated in the rites of the kachina cult. At the Oraibi Patcava ceremony when the Powamui kachina desires to enter the village, he "asks four times for the right to enter Oraibi, and requests permission to show what he can do" (Titiev 1944: 225). At the Powamu ceremony, which occurs just prior to this, the Badger clan, who control Powamu and thus the first half of the kachina cycle, enacts its own arrival at Oraibi and "promises to raise [corn and beans] for Eototo [chief kachina of the ceremony] through the agency of his Powamu ceremony. Thereupon Eototo permits the group to go on, and they proceed into the village" (Titiev 1944:120). Fewkes describes how residents of Hopi pueblos were willing to pay high prices to learn new songs attached to rituals of `foreign' kachinas (Fewkes 1922:494-95). Interestingly for our discussion, Fewkes also describes one Walpi clan known as the Kachina clan, which name he suggests has been given to this clan to commemorate its introduction of kachina worship to Walpi (Fewkes 1901:82). While this is undoubtedly an oversimplification of a complicated process, it indicates that the folk memory which the Hopi still attach to the arrival of various facets of the cult came with immigrant groups to their mesas.

THE AZTEC TRADITION

The Aztec perceived themselves as a chosen people. Semi-nomadic Chichimecs from the northwest of Mexico, they began to move into the Valley of Mexico about 1200. Their myths described their wanderings south from their legendary homeland of Aztlan, possibly driven out by the beginnings of the drought which was to have such a disruptive effect on the entire area. With them traveled their tribal deity, Huitzilopochtli, who through signs and portents chose the site for their great capital of Tenochtitlan. From about 1325 to the Spanish entrada, the Aztec built an empire whose victories were celebrated with human sacrifice and frequent offerings of human blood. Like the Hopi, they practiced a syncretic religion which adopted and continued the rituals of the empires, such as the Toltecs of Teotihuacan, that they replaced, integrated with the demands of their own tribal gods. This appetite for absorbing the deities and beliefs of other Mexican cultures into their already established rituals parallels the Hopi facility for absorbing into their own tradition `alien' rites and beliefs which have proven effective, particularly those related to fertility and rainfall.

THE CEREMONIAL YEAR

The ceremonial year of both Aztec and Hopi cultures were predicated upon the demands and exigencies of the annual agricultural cycle. The winter solstice was the signal, as it has been historically among most agrarian peoples, for the enactment of fire festivals whose primary purpose was to entice the sun back from the darkness of short winter days. Among the Aztec, a great ceremonial race was held at this time imitating the sun's circular route through the cycle of the day and of the year, followed in early March, the first month of the Aztec year, by the Feast of the Sun (Duran 1971:414). Among the Hopi, Wuwuchim or new fire ceremony and Soyal or winter solstice ceremony reenact this agricultural imperative. Following these rituals is a seminal period in the agricultural year, running roughly until the summer solstice. This time is of paramount importance as during it occurs the coincidence of the planting of the fields with the arrival (or dearth) of the rains. On the successful fruition of this coincidence and the ceremonies that attend it, does the life of the people depend.

The Aztec year was divided into eighteen 20-day months, or 360 days, with five `useless days' added at the end of the year. Each month had its ceremonies dedicated to a number of patron dieties and enacted to guarantee a desired result--rain, fertility, success in war or in the hunt, the return of the sun at the winter solstice. For the Aztec, the spring planting cycle fell between the third month of Tozoztontli and the sixth month of Etzalqualitztli (roughly 10 April-28 June), and although each month had prescribed ceremonies specific to it, together they formed integral parts of a continuing cycle that saw the fields planted and the setting up of the first fruits. Tozoztontli was the time of the sacrifice of the blood of children, both in comparatively minor, localized wounds of ears, tongues and shins, and actual child sacrifice of a group of chosen victims. Concurrent with this sacrifice of blood was the letting of childish tears which mimicked the rain, inducing it through sympathetic magic to fall. Further elaborate ceremonies continued through the fourth and fifth months of the Aztec year, culminating in the great feast of symbolic plenty in the sixth month of Etzalqualitztli, when beans and corn were eaten together in a sacred stew reserved for this month alone.

Precisely how the Hopi ceremonial year was divided prior to the Spanish entrada is not recorded. Today it is divided into twelve months, with an additional month added between the eleventh and the final month every two or three years to keep the lunar and solar calendars compatible. Coincident with the arrival of the kachinas at Powamu, which Secakuku (1995:16) calls "perhaps the most complex of all Hopi ceremonies," through their departure at Niman (roughly late January early February through late June) are enacted the ceremonies to ensure plentiful rainfall and abundant crops. Frigout (1979:564) lists Powamu as one of the major Hopi ceremonies and as the `anchor' of the year, when the seed is put into the ground and the rain-bringing rites are performed, it carries the same weight in the Hopi ceremonial year as the Tozoztontli-Etzalqualiztli cycle of rituals carry in the Aztec. With the riches of empire to draw on, the Aztec could afford elaborate, lengthy rituals which with the Hopi seem to have been compressed and selected for their most significant aspects. These aspects appear to reflect and possibly take their origins from the rites of the beginning and the end of the Aztec cycle, specifically those which occur at Tozoztontli and Etzalqualiztli. In this paper a comparison of Tozoztontli and Powamu will be dealt with primarily, reserving an in-depth comparison of Etzalqualiztli and Powamu for a second paper.

A COMPARISON OF TZOZONTLI AND POWAMU

To illustrate some of the parallel aspects of Aztec religion and the Hopi kachina cult, two primary lines of evidence are used. These are a comparison of the Aztec Tozoztontli with the Hopi Powamu festival and a comparison of certain supernatural beings involved in each of these festivals. The table below shows parallel ritual features between the Hopi and the Aztec ceremonies as well as some features that appear to have no identifiable parallel. Let us first examine the Aztec festival of Tozoztontli.

The third month (the Aztec) called Tocoztontli

(also Tozoztontli). On the

first day of this month they observed a feast to the god named Tlaloc,

who

is the god of rains. On this feast they slew many children upon the

mountains. They offered them as sacrifices to this god and his companions,

so that they would give them water (Sahagun 1950-69:2:III:5).

Thus does the sixteenth-century Spanish priest, Bernardino de Sahagun,

describe Tozoztontli, the Aztec feast of purification and fertility

that preceded the beginning of the rainy season in early spring when,

as Diego Duran, another sixteenth-century Spanish priest and commentator,

remarked, "Everyone went out to sow his fields and properties ...

This ceremony constituted the offering of the first flowers to the gods"

(Duran 1971:419-21). The main rituals of the festival were concentrated

on one special day but subsidiary rituals ran throughout the twenty-day

month to the feast of the `Big Perforation' in the fourth month of the

Aztec calendar and culminated in the feast of Etzalqualiztli in the

sixth month at the time of the summer solstice.

Tozoztontli, translated by Sahagun as `the feast of the small perforation',(4) was named after the sacrifices of blood made during that time, and its important elements were: bloodletting among all children under twelve, "which involved a general purification of the mothers" (Duran 1971: 419); social gatherings of feasting and dancing; the offering of the first flowers to the gods; fasting; blood offerings (called penance by Duran); the blessing and sacrifice of children; gift-giving to children; ceremonial hair washing and cutting; and the propitiation of the gods, particularly Tlaloc, the rain god, and Tonantzin, one form of the many-aspected Mother Goddess. The festival concluded with the blessing of the fields. "The farmers used to go out on this day," wrote Duran, "to sanctify the fields. They journeyed thither with incense burners in their hands, going about all the fields, incensing them. Then they went to the place of the idol, god of the planted field, to offer him incense, rubber, food, and pulque" (1971:421).

The month of Tozoztontli, beginning according to Duran on 10 April, marked the celebration of rituals specifically designed to promote the fertility of the fields through the sacrifice of the blood of children and to encourage a fruitful rainy season by the sympathetic magic of children's tears. This last, the ritual of forcing children's tears in imitation of falling rain, was absolutely essential to ensure that Tlaloc, himself, would weep the rainfall that would make the crops grow. Children, therefore, the `first flowers' of the people, were especially prominent during the celebrations because the Aztecs believed that the potent magic of their ready tears and of their blood (the `precious liquid' or chalchihuatl, which fed the gods) would produce an abundant harvest. To this end, blood was drawn from young children whose lives were not intended for sacrifice. Children were also made to inhale chile smoke to cause their tears to fall. At the same time, the lives as well as the blood of young sacrificial victims were offered `upon the mountains' to the god to ensure an abundant harvest and prosperous new year.(5) These sacrifices had ancillary blessings such as the curing aspects associated with the rituals. "[The priests] gave [the people] potions to drink, mixed with the shavings from idols, telling the people that these things would cure illnesses such as diarrhea or fever." With strict adherence to the ceremonies of Tozoztontli, the Aztecs "were made to believe that [their children] could avoid illness and that no evil would befall them" (Duran 1971: 420).

The rites of Tozoztontli were the particular festival of the god Tlaloc, an ancient god in Mexico, who had been incorporated into the Aztec pantheon from those of earlier cultures. "To [Tlaloc] was attributed the rain; for he made it, he caused it to come down ... He caused to sprout, to blossom, to leaf out, to ripe, the trees, the plants, our food" (Sahagun 1950-69: 1:II:2). Tlaloc caused the goddesses responsible for the crops to become fertile, and through their fertility, for the corn to grow. The falling rain was not only Tlaloc's tears, it was also his semen which impregnated the waiting goddesses of vegetation and brought forth abundance. Tlaloc lived on a mountain top, where storm clouds gathered, and was believed to cause swelling or water-related diseases, gout, rheumatism, and dropsy. Associated with Tlaloc and forming his retinue were the tlaloque, a group of strangely-shaped, assistant dwarfs, unpredictable of action but empowered with a potent fertility. The tlaloque were differentiated by the colors of the four cardinal points of the compass.(6) Together with Tlaloc, Tozoztontli was sacred to the goddess Tonantzin or `Our Little Mother', one form of the Mother Goddess and patroness of healers.

When compared to the Aztec festival, the Hopi kachina festival of Powamu or Purification (from pawatani, literally `making things straight' [Voth 1901:71]) contains a number of striking similarities--in schedule, in purpose, in ritual activities and in participants, both human and divine. Powamu is the first great festival of the Hopi agricultural year which welcomes the return of the kachinas to the pueblos. According to Fewkes (1903, reprint 1991:31), it is "one of the most elaborate of all Kachina exhibitions..." Powamu is held about two months earlier than Tozoztontli, at the beginning of February. Mesoamerica and the Southwest utilized different forms of agriculture. Temporal farming in Mesoamerica depended on annual summer rainfall, while intensive farming systems in the Southwest depended on spring rain and irrigation (Braniff Cornejo 1993: 67, 69). As the critical rainfall in the Southwest occurred earlier than in Mesoamerica, the ceremonies, too, began earlier.

Like Tozoztontli, Powamu is a series of spring planting fertility rites enacted just before the coming of the spring rains and held over an 18-day period.(7) They are designed to promote rainfall and agricultural plenty (for a complete description at Walpi, Fewkes 1903, reprint 1991:31ff for descriptions at Oraibi, Titiev 1944:114ff; Voth 1901; also Steward 1931:59ff)(8). Like the Aztec farmers sanctifying their fields, the Hopi farmer "states that Powamu signifies putting the fields in shape `for the approaching planting season'" (Voth 1901:71 note). Its particular focus is on children. The rituals of Powamu include aspects of the Aztec festival of Etzalqualiztli as well as Tozoztontli. Etzalqualiztli was known as the time "when they eat the bean food"(Spence 1912: 48, 56-58). Powamu is referred to by anthropologists as `the bean ceremony', an exact parallel of the Spanish descriptive phrase for Etzalqualiztli. The rituals celebrated at Powamu may, according to Ellis (1989:25), "have accompanied the introduction of beans, which reached the Anasazi about A.D. 600." This would suggest an even earlier basis for some of the Powamu ceremonies, perhaps deriving from a Classic period Teotihuacan root.

The opening rites for both the Hopi and the Aztec festivals involve the forced growth and collecting of `first fruits' (Aztec) or bean sprouts (Hopi) for use in the ensuing ceremonies which subsequently include the cooking and eating of the forced sprouts (Hopi) or mature beans (Aztec). Flower buds and sprouting beans symbolize the rebirth of the earth after winter and its coming fertilization by spring rains. Together with germinated seed corn, the beans are an integral part of the ceremony, primarily because their sprouts can be germinated quickly, grown and eaten during the days of Powamu observance. As at Tozoztontli, it is the children who feature prominently in the Powamu festivities. That they are considered the symbolic seed corn of the people is apparent from the preparation of the 20-day-old baby for his naming ceremony (Fewkes 1920:523).

About 4 o'clock in the morning the grandmother,

or the oldest woman member

of the family, prepares for the event. The room is carefully swept,

the

baby washed, its face covered with sacred meal, an ear of corn tied

to its

breast. This ear of corn is the symbolic mother of the child, and is

carefully preserved through its life.

The prescribed divisions of years involved in the ceremonies held during

the Tozoztontli/Etzalqualiztli cycle and during Powamu are for both

divided into blocks of eight, four, and one. Every eight years during

Tozoztontli, a special ceremony involving large groups of Aztec dancers

dressed as birds, animals, and insects was performed for the tutelary

gods of the festival, Tlaloc, and his associated corn and water goddesses.

Every eight years at Powamu, the Pachava is held. During Pachava, as

many as two hundred kachinas dressed as birds, animals and insects dance

together in the main plaza (Ellis 1989:23). The stated purpose of this

performance is to entertain the exhausted gods while they recover their

powers. Every fourth year among the Aztecs, a subsequent feast of Tlaloc

was held called Izcalli or `growth'. This, too, focused on children.

According to Duran (1971- 465), the feast propitiated the rain which

caused the dual growth of both corn and children, and a boy and a girl

were sacrificed.

Every fourth year at Powamu, a group of children, now considered grown up enough, are initiated into the Powamu fraternity. In token of this `growth', the boys will be trained to act in future as kachinas and leaders of the ritual kachina dances which secure rain and corn for their people. For the Aztec, this special group of children would have been the chosen ones, those selected for sacrifice in order to carry to the gods in person the prayers of their people for rain. For both Aztec and Hopi, these children form a unique bond with the powers which control life. The remaining children who have reached the age of 7-10 years and are considered ready are initiated into the Kachina Society. These children participate in initiation ceremonies (discussed below) which mimic the offerings of blood and tears that the Aztec required of all their children during Tozoztontli. The more benevolent and less blood-oriented world view of the Hopi has dispensed with the literal sacrifice of some children while maintaining the living expression of blood and tears of all, and has reinterpreted the reasons for the rites to fit a more socially acceptable justification. Modern Hopi dogma states that the purpose of the ritual is to initiate the children into adult society and reveal to them the human nature of the visible kachinas. Yet the age at which this ritual occurs, between seven and ten, is somewhat younger than is normally looked for in such rites of passage when the onset of puberty generally dictates the timing. Like the Aztec, the Hopi involve their children in this important ceremony from a very young age.

For the juvenile participants of both the Hopi Powamu and the Aztec Tozoztontli, the desired increase of rainfall and resultant fertility is extended to include a rite of passage. Part of this rite is marked by the ceremonial cutting of hair in particular and peculiar styles that indicate participation in the communal rituals at different levels--initiate and non-initiate (Duran 1971:420; Voth 1901:83). It also involves ritual hair washing, symbolic presents in the form of small images of gods (Aztec) or kachinas (Hopi), the use of incense (Aztec, copal; Hopi, ritual pipes), special foods (particularly at Etzalqualiztli) and offerings to the powers which control the rain (Aztec, beans and corn, blood and tears; Hopi, bean sprouts, cornmeal and tears). There is also in both rituals a concentrated attempt on the part of the adults to keep secret the mechanics of the ceremonies from the children so that the awe-inspiring `magic' of the rites will be preserved (Titiev 1944:114). The children, who have received gifts and tokens of blessing (kachina dolls, bows and arrows) as encouragement each year prior to the year of their initiation, are in that year expected to offer the gift of self-sacrifice to the gods.(9) During Tozoztontli, according to Diego Duran (1971:419-420), "all children under twelve were bled, even breast-fed babes. Their cars were pierced--their tongues, their skins." This implies a communal sacrificial offering. Although he confuses penance with blood offering, Duran goes on to say:

Certain heathen old men, the soothsayers of

each town, went from home to

home this day, inquiring about the children who had fasted and done

penance

by pricking their cars and other parts. If they had fasted and had

accomplished what was required of them according to the pagan law, red,

green, blue, black, o yellow threads (any color which the soothsayers

liked, in fact) were tied to their necks. To the thread these men tied

a

small snake bone, a string of stone beads, or perhaps a little figure.

The

same was attached to little girls' wrists ...

This passage refocuses Tozoztontli as a ritual with special meaning

for children, both male and female, of an age to make self-generated

blood offering, to fast and to understand "what was required of

them according to the pagan law ..." Although Duran does not say

so unequivocally, he implies some sort of rite of passage for older

children who have reached the age of twelve or puberty and who must

have performed the rituals of Tozoztontli many times during their childhood.

For these children, at the threshold of their adult life, the later

performances would have had special, particular meaning and possibly

subtly differentiated responsibilities.

It was not only the blood but the tears of the children which were important. For the Aztec, the tears of sacrificed children created rain by sympathetic magic. Today in Mexico, this belief is incorporated in the figures of the llorones, or weepers, which as clay figures of weeping children are still used on the altars or ofrendas during Dia de los Muertos (Carmichael & Sayer 1995:152). This belief in the potency of human imitation (tears) to induce divine initiation (rainfall) continues in the Powamu rituals, although today on the Hopi mesas, a clear understanding of the magical connection between the children's tears and future rainfall has been submerged in the modern Hopi explanation of the ritual. According to Voth's informants at Old Oraibi, "a good deal of obscurity exists in the tradition as to the details of the manner in which the custom [of whipping] became a part of the Powamu ceremony" (Voth 1901:105). Child flogging, to produce the required tears and frequently the blood of offering as well, has been substituted for outright child sacrifice but still imitates the remaining rituals that the Aztec required of their own children.(10)

One after another, regardless of sex, the candidates

are placed on a sand

painting by their ceremonial parents to receive four severe lashes from

either of the Hu Kachinas. The boys are naked and hold one hand aloft

while

they clasp the genital organs with the other to prevent their being

struck;

the girls wear their dresses and lift both hands high above their heads.

(Titiev 1944:116; also see Steward 1931:65-66)

Voth's description of the initiation he witnessed at Old Oraibi at the

turn of the century is very similar (1901: 103-5): "The children

tremble and some begin to cry and to scream ... (as) one of the Ho Katchinas

whips the little victim quite severely ... in short, pandemonium reigns

in the kiva during this [time]." The description of the child initiates

as victims reflects the original purpose of the ceremony. A direct correlation

between the act of whipping, which causes the children to cry and consequently

the rain to fall, is described by Steward (1931:66).

After the whipping of the children, Kachina

chief gives Dumas and Dunwup

[the whipper kachinas] each a handful of turkey feathers, which he tells

them are clouds and requests them to "take these home to their

people and

ask them to send rain and good crops...." When they arrive [at

a shrine

called Kuwawaimuvek at the southwest point of First Mesa], Dumas kachina

places the feathers on the shrine and addresses a prayer to the Clouds:

"Here, we have brought you these feathers which our fathers handed

to us to

ask you to bring rain to the crops and make them grow."

The ceremonial meaning of these events is inherent in their sequence.

The imitative magic of the children's tears are joined to the imitative

magic of the feather `clouds' which are then ritually presented to the

rain gods by the whippers at a prescribed shrine, together with additional

prayers For abundant rainfall. It is the initiation of the children

and their tears which have given the power of the clouds into the hands

of Dumas and Dunwup.

Subsequent tears are also plentiful when, during the initiation rituals, the children discover that the visible kachinas that they have been used to regard with awe and fear are actually men known to them dressed up and playing parts, a psychological shock of greater impact than that on a young child of Western society being roughly informed that Santa Claus is a myth. This sudden knowledge is very upsetting to a number of the children and one girl, as an adult, remembered that, "I cried and cried into my sheepskin that night, feeling I had been made a Fool of. How could I ever watch the Katchinas dance again?" (Eggan 1943:372 note 34). Yet these tears, too, are sympathetic magic. As a reward at the end of the Powamu rituals, all the children receive gifts and tokens from the kachinas. "At sunrise of the last day of Powamu, two personations from each kiva distribute the sprouted beans, [kachina] dolls, bows and arrows, moccasins, and other objects which have been made for that purpose" (Fewkes 1903, reprinted 1991:39). The bows and arrows symbolize the rainbow and lightning bolt and the interaction of earth and sky (Ellis & Hammack 1968: 35). These gifts are distributed among the children of the Hopi pueblos in recognition of their contribution to the ceremonics just completed.

Like the rituals held during Tozoztontli, there are curing aspects connected with Powamu. For the Aztec, Tonantzin was the patroness of healers, and Tlaloc was believed to have a special connection with rheumatism. Correspondingly, the Hopi, too, believe that the careful observance of Powamu can bring healing for that disease (Titiev 1944: 120). For an adult at this time, purification and abstinence from sex, foregoing of the use of salt, and a strict attention to prescribed vigils held in the kiva, contributes to the power of rain-bringing and a fine-tuning of natural harmonics or `making all things straight'.

SUPERNATURAL BEINGS

If the Aztec festival of Tozoztontli and the Hopi Powamu have common roots, then it should be possible to align some of the kachinas with their Mesoamerican counterparts. It should be noted parenthetically that for the Hopi, katchinas are not gods. They are animistic and ancestral spirits who act as messengers between the gods and men. They may be impersonated by men; they may be represented by carved wooden figures, frequently as a learning tool for children. They are the benevolent well-wishers of the people. For the purpose of cross-cultural comparison, let us examine three kachinas most important to Powamu--Eototo, his lieutenant Aholi, and the Powamu kachina itself.

Head of all the kachinas at the Powamu festival is Eototo. Dressed in white, with a white mask and carrying a gourd of sacred water, a pouch of sacred meal and, at Walpi, a bundle of sheep scapulae (Fewkes 1903, reprinted 1991:76), this kachina is one of the most important and prominent kachinas to participate in the ceremonies to call the rain. Titiev calls him "the spiritual counterpart of the Village chief" (Titiev 1944:114), who controls the kachina's mask and is the only one allowed to impersonate him. According to Parsons, Eototo is one of two kachinas (the other being Aholi) who perform water-pouring during the central Powamu ritual as a mimetic rite: "`thus we hope rain will come copiously after our corn is planted in the fields'" (Parsons 1939: 376). At Old Oraibi, Eototo "goes to the north end of the kiva, rubs a handful of sacred meal to the north side of the hatchway and then pours a little water into the kiva, which is caught up in a bowl by a man standing on a ladder" (Voth 1901:113). This offering to the north is then repeated to the other three cardinal directions. Water and the fruitfulness of the earth are thus what his appearance at Powamu promises to the Hopi. Fewkes describes additionally a connection at Walpi between Eototo and Masau, the ruler of the underworld (1902:19-24). Eototo is an extremely old kachina, and Underhill's Hopi informants state that: "Aholi and Eototo kachinas went to the Red Land of the south and brought back squash, after long wanderings" (Underhill 1954:651), an echo of the legend on which Powamu itself is based. Eototo does, in fact, appear to derive from the red land of the south, from the primordial Aztec god of creation, Ometeotl, a version of whose name he appears to have adopted.

Ometeotl in his conjoined male and female forms was the continuing creator of life, of whom the rain god Tlaloc (patron of the Aztec festival of Tozoztontli) was one aspect and the Mother Goddesses (among them Tonantzin) who ripened the corn another. "For to the Nahuatl mind," Leon-Portilla tells us, "all activity was determined by the intervention of Ometeotl" (Leon-Portilla 1963:99). Ometeotl was the Aztec approximation of Godhead and, as such, was the ultimate aspect of all other principal gods of the Aztec pantheon. The arrival of Eototo/Ometeotl at the Hopi mesas is the arrival of the highest aspect of each of the important gods, joined and expressed in one form. Eototo knows all of the ceremonies of the Hopi, an indication of his omniscient control of universal creative forces. As part of the duality of Ometeotl is his aspect as Mictlantecuhtli, lord of the dead, paralleling the Eototo-Masau connection at Walpi. Ometeotl "inhabited the shadows" of the underworld of Mictlan and therefore was associated with the dead, those who had departed, who in the minds of the Hopi become one with the kachinas (Fewkes 1920:526), giving Eototo and Ometeotl strikingly similar connections and attributes. To the Aztec, Ometeotl controlled the rain as Tlaloc, the sun as Tonatiuh, the corn as the Mother Goddesses. To the Hopi, as Eototo, he brought the "gifts of nature" back to the villages at Powamu. With Eototo always appears his companion or lieutenant, Aholi,(11) one of at least three kachinas who appear at Powamu--Aholi (also Ahul), Qoqlo and Ongchoma--who seem to take their point of origin from one of Mesoamerica's most popular gods, Quetzalcoatl. This, too, fits the Aztec concept of things since, "as a symbol of his intangible quality, as the embodiment of wisdom and of the only truth on earth, Ometeotl was personified in the legendary figure of Quetzalcoatl" (Leon-Portilla 1963:98). The indissoluble connection between the two gods thus continues to be preserved in the indissoluble connection between the two kachinas.

Quetzalcoatl, the `Feathered Serpent', seems to appear in many guises among the kachina (Ellis & Hammack 1968:42). In his Maya form--Kukulcan--he appears as Palulukonti, the central actor in the Hopi serpent festival which is connected with Powamu (Dutton 1975: 51-52). As Aholi in Powamu, he acts in concert with Eototo and participates in mimetic water rites. His costume is particularly evocative as he appears before the Hopi in a modified version of Quetzalcoatl's signature conical cap, called ocelocopilli by the Aztec for the ocelot fur from which it was made, and displays a picture of Alosaka, god of fertility, on his cloak or blanket. The colored dots on his cloak, which to the modern Hopi represent the various colors of corn--white, red, blue, yellow--mimic the splashes of rubber on Quetzalcoatl's cloak which to the Aztec had connections with the element of water. Quetzalcoatl was the god of fertility, discoverer of corn, lord of the winds, establisher of the calendar and priestly ritual. As bringer of all agricultural processes to mankind, he parallels Powamu's legendary creator by whose efforts and sacrifice the rituals that called the rain and caused the corn to grow were first brought to the Hopi. As Aholi kachina, he carries in his hand a wand marked with a star on the end, and as the plumed water serpent, two jars dedicated to him are painted with pointed star emblems (Fewkes 1920:507). This parallels the symbol of Kukulcan or Quetzalcoatl, who was in another aspect the Lord of the Morning Star (Schaafsma 1980:238).

A Hopi legend retailed by Eggan seems to underscore the adoption of the Mesoamerican mythology of Quetzalcoatl into the kachina cult. According to one Hopi informant, they "had long anticipated the return of an `elder brother' [Pahana, the lost brother of the east](12) who instead of crystallizing existing limitations was to have dealt effectively with all their difficulties, thus permitting them to `inherit the earth'" (Eggan 1943:360). Aholi's name appears to derive from the Hopi word ahulti, or `return'(Fewkes 1903:122), which was the promise that the departing Quetzalcoatl made his people when he fled the Toltec capital of Tula for the mythical land of Tlillan Tlapallan to the east.(13) In his manifestation as the benevolent protector of mankind, Quetzalcoatl seems to also appear at Powamu as Qoqlo, a "generous and kindly kachina ... [who] prophesies good crops and promises toys for the children....," and as Ongchoma, the `Compassionate Kachina', "who sympathizes with the children who are about to be whipped ..." (Colton 1959:21,24). This multiplication into several kachinas of various facets of Quetzalcoatl's syncretic nature points to those of the god's understood functions that the Hopi considered most important and thus selected out for emphasis (Beal 1974: 59). As Aholi, Quetzalcoatl offers agricultural abundance through both planting and religious rituals which he has ordained, through the corn that he has discovered; as Qoqlo and Ongchoma, he offers generosity and compassion to the children who bear the heaviest burden of a sacrifice that ensures the efficacy of those rituals.(14)

The signature kachina of Powamu is the Powamui kachina, itself; described by Titiev as the leader of the Badger clan (who have responsibility for the kachina cult), and an avatar of Muyingwa, principal god for germination (Titiev 1944:120). The Powamui kachina appears as a group of identical kachinas, unmasked at the night ceremonies but wearing a red mask with diagonal hachures on the cheeks in the plaza ceremonies. Powamui's body is painted red, with one green and one yellow shoulder, and on his head are flowers carved of wood or made of painted corn shucks (Fewkes 1903, reprinted 1991:84-5; Colton 1959: 30). Powamui appears on the last day of Powamu and is in a sense the fruition of the proper ceremonial observances that have proceeded his arrival. The gifts given to the children on this day symbolize the even greater gifts of fertility given to the entire community. The kachinas have, through the correct observances of Powamu by the Hopi, called the rain, purified the people, and sanctified the fields for planting, thus ensuring the return of Quetzalcoatl's great gift to mankind, corn. At the conclusion of Powamu, the prayers and properly performed rituals of the people act in concert with the offerings of their children's tears and blood to produce the appearance of Powamui, the promise and incarnation of future abundance.

The origin of the Powamui kachina, too, appears to have Mesoamerican roots which can be found in the god Xochipilli, the Aztec prince of flowers,(15) of games, sports(16) and dances, whose cult included Centeotl, the corn god, and that god's many female manifestations. Xochipilli's symbols are the flowers that are a part of his name (xoch = flower), the butterfly, the tonallo (a four-pointed glyph representing the sun), and an elaborate headdress. It is suggested here that the classification of kachinas distinguished by elaborate tabletas, such as Poli Sio Hemis Kachina, whose tableta carries a distinctive butterfly, and Hemis (or Jemez) Kachina, represent a spectrum of Pueblo adaptations of Xochipilli, his power and his emblems. Duran (1971:428) states that at one of the most sacred dances, Toxcanetotiliztli, held in the fifth month of the Aztec calendar during the spring planting rituals: "All crowned themselves with headdresses or mitres made up of small painted wreaths, beautifully adorned like latticework ... These crowns of headdresses were called tzatzaztli, which means `something wrought like a lattice'." A possible hypothesis is suggested that the Aztec tzatzaztli may have been the origin of the kachina tableta. At Powamu, the flowers and the tonallo of Xochipilli have been merged into the stylized crown of pointed flowers which the Powamui kachina wears, and the colors of the tonallo are echoed in Powamui's multi-colored body paint. It is the appearance of this kachina which signals the final act of Powamu or Purification for which the days of carefully prescribed ritual were performed. He is the personification of future fertility, and his coming assures the people that all has been once again put straight.

CONCLUSION

When discussing similarities between Aztec deities derived from earlier Mesoamerican roots and Hopi kachinas, two caveats should be kept in mind. First, a concomitant factor of cultural processing is functional blurring. As theirs was a strongly syncretic religion, the functions of many of the Aztec gods overlapped. Among the Aztec, for example, Chicomecoatl, `Seven Serpent', was one of the most ancient and important goddesses of vegetation. Yet she was also Chicomolotzin, `Seven Ears of Corn', and related to her were Xilonen, the female god of green corn, and Ilamatecuhtli, `the Lady of the Old Skirt', or goddess of the dry ear. All of these were probably syncretic facets of a common deistic urge among different culture groups in southern Mexico. Tonatiuh was the Aztec sun god, but Huitzilopochtli, too, was a sun god, and the god of fire could appear as Tezcatlipoca, who discovered that element, or as Xiuhtecuhtli, the `Lord of the Year', Huehueteotl, the `Old God', or Ixcozauhqui, `Yellow Face'. Therefore, when multiple usage or many-faceted gods and their rituals were passed north through various cultural filters, they almost certainly arrived not precisely as they began. Overlapping functions and some distortion of their myths and principals were inevitable. For the peoples of the Southwest in their semi-arid, drought-ridden highlands, climatic events which often determined religious priorities were different from the Mesoamericans with their impressive cities built in the Mexican highlands or further south in the midst of the tropical jungle. Selection and adaptation to fit local requirements were inevitable and different aspects of a god might thus be stressed to reflect these different needs (Young 1994:108).

Wilcox (1991:102) speaks of Mesoamerican innovation generating successive waves of change as versions of ideas, religious ideas included, diffused outward over time. This may be a simplistic model but the possible existence of an Aztec interpretation of important Mcsoamerican rituals and supernatural beings in the kachina cult indicated by this paper attests to the results if not the mechanisms of cultural interaction. It is significant that Hays describes kachina representations on prehistoric pottery dating to about 1300 A.D. as being recognizable to modern Hopi, indicating that a "remarkable continuity of traditions exists" for certain aspects of the cult (Hays 1994: 61). After the Spanish entrada, the pueblos of the Southwest were ultimately cut off from the old religions to the south and battered by the militant religious proselytizing of the Catholic Church, which caused severe dislocation among pueblo peoples and their cultural practices (C. Schaafsma 1994:121-22; Wright 1994:142). During this period the pueblos were left to develop the kachina cult without reference to Mesoamerica but under the shadow and within the influence of Spanish Christianity. Refugees from Spanish oppression among the eastern Rio Grande pueblos brought their own variant kachinas and those kachinas' observances to western pueblos where they were added to pre-existing kachina ceremonies. Such upheaval would have allowed further inconsistencies to enter in and further blurring of meaning and function may have occurred. Change has always been a function of cultural stress and two operating mechanisms in the kachina cult, syncretism or the joining of aspects of different gods in one kachina, and desyncretism or the isolating of a special or significant aspect of a particular god by creating another individual kachina to represent that aspect, added to cult development dynamics.

This brings us to the second caveat. For half a millennium, the kachina cult rituals and ceremonies were passed down orally until non-pueblo explorers, and later, anthropologists and ethnographers, began to make notes. This period of purely oral transmission of data may also have allowed distortion to enter in, no matter how carefully attempts were made to keep the sacred knowledge pure. Also operating against this desire for ceremonial purity was the need to modify rituals to meet the changing circumstances of post-Columbian life. According to Wright (1994:141):

Despite the apparent longevity of some chief

kachinasthere are processes

whereby change can and does occuroften within a relatively short interval.

Variations can appear that will eventually shift not only the structure

within which these beings act but their appearance as well.

In addition to this, says Wright (1994:145), "all kachinas change

because they are not only a religious statement but also a creative

outlet and consequently are subject to improvisation." Hopi initiates

are continually cautioned "not to tell" anyone about what

they have learned during the ceremonies and secrecy, too, would have

added over time some degree of distortion (Titiev 1944:115). Therefore,

when examining specific kachinas as interpreted by Hopi of the twentieth

century, there are bound to be differences between those kachinas and

the Mesoamerican deities that may be their points of origin. As Curtis

Schaafsma so rightly points out (1994:122): "Any conclusions about

this topic based primarily upon ethnographic evidence are almost certain

to be faulty and of little value."(17) Yet enough similarity remains

in many cases that it is still possible, despite these caveats, to peel

away accretions and adaptations and reveal what appears to be an Aztec

version of a Mesoamerican deity at the core of the kachina. Cultural

interaction is a fact of human existence and although Mesoamerican influences

interpreted by Aztec sources appear to have passed to the north to be

incorporated by ancestors of the Hopi in their belief systems, this

does not lessen the achievements of the recipient culture which has

with time created of disparate elements an harmonious system uniquely

their own.

NOTES

(1.) In this paper, the term `Mesoamerican' includes the pre-Columbian cultures of present-day Mexico, and the Maya culture further to the south. The scope of this article does not allow space for discussion of such loaded terms as `Greater Southwest' and `Gran Chichimeca' and the reader is referred to Woosley and Ravesloot 1993, for various articles discussing these geographical and cultural delimiters.

(2.) It should be remembered that, for the most part, the Aztecs inherited their religion from earlier cultures and thus the gods and ceremonies of Aztec culture are older than the Aztecs themselves.

(3.) Linguistic comparisons between two cultures without written languages, one which in its essentials was destroyed in the mid-sixteenth century and one which continues today, is tricky at best. Added to this is a deep reluctance on the part of the Hopi toward candid discussion regarding anything pertaining to their religion. I have made a number of linguistic hypotheses in this paper and have noted the origin of most of them. The rest remain, for better or worse, solely my own suggestions.

(4.) Duran describes the name as referring to a constellation of stars shaped like a bird with a bone piercing its body. Some astral occurrence related to the constellation (Taurus?) and admittedly not understood by Duran seems to have been the signal to begin the feast (Duran 1971:418).

(5.) According to Duran (1971:412), the Aztec new year began on 1 March.

(6.) In the tlaloque may lie the origins of the Hopi Koyemsi or Mud Head Clowns. Parsons (1939:376) quotes a Hopi as saying, "The Koyemsi represent the rain, therefore we throw water on them."

(7.) This varies according to the number of rituals chosen for enactment in any given year.

(8.) Fewkes, who wrote extensively on the particular group of rituals associated with Powamu, seems to have developed a blind spot where the rain-making aspects of the ceremony were concerned. Although he reiterates on numerous occasions that "the majority of all [Hopi] ceremonies are for rain and abundant crops, and all their prayers to clan or other gods are to bring these things" (Fewkes 1901:92), he consistently marginalizes that goal. Apparently, Fewkes reached the conclusion that despite the need for rain, the Hopi kachina cult was primarily focused on the sun god, even going so far as to interpret lightning symbols not as precursors to the devoutly desired rainfall but as light source corollaries to the sun (Fewkes 1920, 523). His persistence in ignoring the rain-making aspects of Powamu and of many of its related rituals such as Palulukonti, tends to throw his subsequent interpretations off balance and distort the meaning of certain aspects of the rituals in his descriptions.

(9.) Fewkes describes the legend of youthful self-sacrifice among the Hopi of Walpi which is given as the origin of child whipping (Fewkes 1920:525). The framework of the story is of interest as it concerns the "very old times ... before the seeds of corn and other food which form the diet of the Hopi were brought to mankind," and describes the Hopi people sitting "around a large sacred stone bemoaning their lot." To save his people from their despair, a young man volunteers to make a perilous journey, suffer danger and physical torture in order to bring back the rituals that will allow his people to reap "the gifts of nature."

(10.) Constant aspersing which symbolizes the rain combined with ritual smoking or `blowing clouds' intensifies the power of the magic for the Hopi (Parsons 1932: 370-74).

(11.) The spelling of the name varies. According to Titiev (1944:114): "There is no Aholi Katcina at First Mesa, but Ahul, who is unknown at Oraibi, plays an important part in the Powamu there."

(12.) The color symbolizing the east was white, hence the extrapolation of "a white brother," which may or may not be precisely what the original legend predicted.

(13.) Fewkes perceives this `return' as a reference to the returning sun (Fewkes 1902:16).

(14.) It should be noted that the final syllables of the names of a number of katsinas, such as `qlo, `oaqa, `qoto, `qa-o, `quoqu, and `qala, might originally have derived from the Nahuatl word `coatl' or snake. Although Hopi and Nahuatl are members of the same language group, the persistence and frequency of variants of this ending in katchina names may indicate just how influential and important Mesoamerican deities personifying the snake-water-corn connection, such as Quetzalcoatl, Chicomecoatl and Cihuacoatl, were in the American Southwest between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.

(15.) Flowers for the Aztec represented spiritual power and had associations with fire (Hill 1974:117).

(16.) Three days after the appearance of Powamui, a racing season begins (Titiev 1944:120).

(17.) In this regard, Titiev comments: "It is by no means certain that any of the interpretations of specific ritual acts are correct. No informant is entirely trustworthy when the subject deals with sacred matters. Then too it often happens that the true explanation for certain actions is as much a mystery to the performers as it is to us, and they make up `explanations' to answer one's questions" (Titiev 1944:117 note 480).

REFERENCES

Adams, E. Charles 1991 The Origin and Development of the Pueblo Kachina Cult. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Adams, E. Charles and Deborah Hull 1980 The Prehistoric and Historic Occupation of the Hopi Mesas. In Hopi Kachina: Spirit of Life. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Altschul, Jeffrey H. 1997 From North to South: Shifting Sociopolitical Alliances During the Formative Period in the San Pedro Valley. In Prehistory of the Borderlands: Recent Research in the Archaeology of Northern Mexico and the Southern Southwest, pp. 57-69. Edited by John Carpenter and Guadalupe Sanchez. Archaeological Series No. 186. Tucson: Arizona State Museum.

Baugh, Timothy G. and Jonathon E. Ericson 1993 Trade and Exchange in a Historical Perspective. In The American Southwest and Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Exchange, pp. 3-20. Edited by Jonathon E. Ericson. New York: Plenum Press.

Beals, Ralph L. 1974 Cultural Relations Between Northern Mexico and the Southwest United States: Ethnologically and Archaeologically. In The Mesoamerican Southwest.' Readings in Archaeology, Ethnohistory and Ethnology, pp. 90-102. Edited by Basil C. Hedrick, J. Charles Kelley, and Carroll L. Riley. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Bradley, Ronna J. 1993 Marine Shell Exchange in Northwest Mexico and the Southwest. In The American Southwest and Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Exchange, pp. 121-151. New York: Plenum Press.

Braniff Cornejo, Beatriz 1993 The Mesoamerican Northern Frontier and the Gran Chichimcca. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 65-82. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Breitburg, Emmanuel 1993 The Evolution of Turkey Domestication in the Gran Chichimcca and Mesoamerica. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 153-172. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Brody, J. J. 1977 Mimbres Art: Sidetracked on the Trail of a Mexican Connection. American Indian Art2, 4: 26-31.

Carmichael, Elizabeth and Chloe Sayer 1991 The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Carpenter, John P. 1997 Passing through the Netherworld: New Insights from the American Museum of Natural History's Sonora-Sinaloa Archaeological Project (1937-1940). In Prehistory of the Borderlands: Recent Research in the Archaeology of Northern Mexico and the Southern Southwest, pp. 113-127. Edited by John Carpenter and Guadalupe Sanchez. Archaeological Series 186. Tucson: Arizona StateMuseum.

Caso, Alfonso 1958 The Aztecs: People of the Sun. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Colton, Harold S. 1959 Hopi Kachina Dolls: With a Key to Their Identification, Historic Background, Processes, and Methods of Manufacture. Revision of 1949 edition. Albuquerque:University of New Mexico Press.

Dean, Jeffrey S. and John C. Ravesloot 1993 The Chronology of Cultural Interaction in the Gran Chichimeca. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 83-103. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Dockstader, Frederick J. 1985 The Kachina and the White Man. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Doelle, William H. and Henry D. Wallace 1997 A Classic Period Platform Mount System in the Lower San Pedro River, Southern Arizona. In Prehistory of the Borderlands: Recent Research in the Archaeology of Northern Mexico and the Southern Southwest, pp. 71-84, Edited by John Carpenter and Guadalupe Sanchez. Archaeological Series No. 186. Tucson: Arizona State Museum.

Doolittle, William E. 1993 Canal Irrigation at Casas Grandes: A Technological and Developmental Assessment of its Origins. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 133-151. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Doyel, David E. 1993 Interpreting Prehistoric Cultural Diversity in the Arizona Desert. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 39-64. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Duran, Fray Diego 1971 Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar. Translated and edited by Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heydon. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Dutton, Bertha P. 1975 American Indians of the Southwest. Reprinted 1983. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Eggan, Dorothy 1943 The General Problem of Hopi Adjustment. In American Anthropologist 45: 357-73.

Ellis, Florence Hawley 1989 Some Notable Parallels Between Pueblo and Mexican Pantheons and Ceremonies. Anthropology Teaching Museum Research Paper Number 2. Theodore R. Frisbie, Series Editor. Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ellis, Florence Hawley and Laurens Hammack 1968 The Inner Sanctum of Feather Cave: A Mogollon Sun and Earth Shrine Linking Mexico and the Southwest. American Antiquity 33: 25-44.

Fewkes, Jesse Walter 1893 Awatobi: An Archaeological Verification of a Tusayan Legend, American Anthropologist 6:363-75.

1898 The Growth of the Hopi Ritual. Journal of American Folklore 11:173-94.

1901 An Interpretation of Kachina Worship. Journal of American Folklore 14: 81-94.

1902 Sky-god Personations in Hopi Worship. Journal of American Folklore 15: 14-32.

1903 Hopi Kachinas. Republished 1991. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications.

1920 Sun Worship of the Hopi Indians. Smithsonian Institute Annual Report for 1918, Washington, D.C., pp. 493-526.

1922 Ancestor Worship of the Hopi Indians. Smithsonia Institute Annual Report for 1921, Washington, D.C., pp. 485-506.

1924 The Use of Idols in Hopi Worship. Smithsonian Institute Annual Report for 1922, Washington, D.C., pp. 377-97.

Frazier, Kendrick 1986 People of Chaco: A Canyon and its culture. New York: W.W. Norton.

Frigout, Arlette 1979 Hopi Ceremonial Organization. In Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 9: Southwest, pp. 564-76. Edited by Alfonso Ortiz. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Griffith, James Seavey 1983 Kachinas and Masking. In Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 10: Southwest, pp. 764-77. Edited by Alfonso Ortiz. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Haury, Emil W. 1974 The Problem of Contacts Between the Southwestern United States and Mexico. In The Mesoamerican Southwest: Readings in Archaeology, Ethnohistory and Ethnology, pp.90-102. Edited by Basil C. Hedrick, J. Charles Kelley, and Carroll L. Riley. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Hays, Kelley Ann 1994 Kachina Depictions on Prehistoric Pueblo Pottery. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World, pp. 47-62. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Hibben, Frank C. 1967 Mexican Features of Mural Paintings at Pottery Mound. Archaeology 20, ii: 84-87.

Hill, Jane 1974 The Flower World of Old Uto-Aztecan. Journal of Anthropological Research 48:117-44.

Kelley, J. Charles 1993 Zenith Passage: The View from Chalchihuites. In Culture and Contact: Charles C. DiPeso's Gran Chichimeca, pp. 227- 50. Edited by Anne I. Woosley and John C. Ravesloot. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

1966 Mesoamerica and the Southwestern United States. In Handbook of Middle American Indians 4: 95-110. Edited by Robert Wauchope. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Leon-Portilla, Miguel 1963 Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Lopez, Cesar Quijada 1997 Algunas Consideraciones Arqueologicas del Rio San Pedro. In Prehistory of the Borderlands: Recent Research in the Archaeology of Northern Mexico and the Southern, pp. 47-55. Edited by John Carpenter and Guadalupe Sanchez. Archaeological Series No. 186 Tucson: Arizona State Museum.

Mathien, Frances Joan 1991 Political, economic, and demographic implications of the Chaco road network. In Ancient Road Networks and Settlement Hierarchies in the New World, pp. 99-110. Edited by Charles D. Trombold. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Mathien, Frances Joan and Randall H. McGuire, editors 1986 Ripples in the Chichimec Sea: New Considerations of Southwest-Mesoamerican Interaction. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press,.

McGuire, Randall H. 1993 The Structure and Organization of Hohokam Exchange. In The American Southwest and Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Exchange, pp. 95-119. Edited by Jonathon E. Ericson. New York: Plenum Press.

1980 The Mesoamerican Connection in the Southwest. Kiva 4: 3-38.

Parsons, Elsie Clews 1933 Some Aztec and Pueblo Parallels. American Anthropologist 35:611-31.

1939 Pueblo Indian Religion. 2 volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Plog, Stephen 1993 Changing Perspectives on North and Middle American Exchange Systems. In The American Southwest and Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Exchange, pp. 285-92. Edited by Jonathon E. Ericson and Timothy G. Baugh. New York: Plenum Press.

Reyman, Jonathan E. 1978 Pochteca Burials at Anasazi Sites? In Across the Chichimec Sea, pp. 242-59. Edited by Carroll L. Riley and Basil C. Hedrick. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press,

Riley, Carroll L. 1988 The Frontier People: The Greater Southwest in the Protohistoric Period. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Riley, Carroll L. and Basil C. Hedrick 1978 Across the Chichimec Sea. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Riley, Carroll L. and Joni L. Manson 1991 The Sonoran connection: road and trail networks in the proto historic period. In Ancient Road Networks and Settlement Hierarchies in the New World, pp. 132-144. Edited by Charles D. Trombold. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Sahagun, Fray Bernardino de 1950-1969 General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe: School of American Research.

Schaafsma, Curtis F. 1994 Pueblo Ceremonialism from the Perspectives of Spanish Documents. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World, pp. 121-37. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Schaafsma, Polly 1980 Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. Santa Fe: School of American Research; Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

1994 Kachinas in the Pueblo World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Schaafsma, Polly and Curtis F. Schaafsma 1974 Evidence for the Origins of the Pueblo Katchina Cult as Suggested by Southwest Rock Art. American Antiquity 3, 4, 1: 535-45.

Secakuku, Alph H. 1995 Following the Sun and Moon: Hopi Kachini Tradition. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing.

Spence, Lewis 1912 The Civilization of Ancient Mexico. Cambridge University Press; New York: G.P. Putnum's Sons.

Spicer, Edward H. 1986 Cycles of Conquest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Steward, Julian H. 1931 Notes of Hopi Ceremonies in Their Initiatory Form in 1927-1928. American Anthropologist 33: 56-79.

Teiwes, Helga 1991 Kachina Dolls: The Art of Hopi Carvers. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Thompson, Marc 1994 The Evolution and Dissemination of Mimbres Iconography. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World, pp. 93-105. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Titiev, Mischa 1944 Old Oraibi: A Study of the Hopi Indians of Third Mesa. Papers of the Peabody Museum American. Archaeol., Ethnol., Volume 22, Number 1. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Underhill, Ruth M. 1954 Intercultural Relations in the Greater Southwest. American Anthropologist 56: 645-62.

Voth, H. R. 1901 The Oraibi Powamu Ceremony. Field Museum Publication Number 61, Anthropology Series, Volume 3, Number 2. Chicago: Field Museum.

Weigand, Phil C. and Garman Harbottle 1993 The Role of Turquoises in the Ancient Mesoamerican Trade Structure. In The American Southwest and Mesoamerica: Systems of Prehistoric Exchange, pp. 159-77. Edited by Jonathon E. Ericson. New York: Plenum Press.

Wilcox, David R. 1991 The Mesoamerican Ballgame in the American Southwest. In The Mesoamerican Ballgame, pp. 101-25. Edited by Vernon L. Scarborough and David R. Wilcox. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

White, Leslie A. 1934 Masks in the Southwest. American Anthropologist 36: 626-28.

Wright, Barton 1977 Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls. Reprinted 1993. Flagstaff: Northland Publishing.

1994 The Changing Kachina. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World, pp. 139-45. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Young, M. Jane 1994 The Interconnection Between Western Puebloan and Mesoamerican Ideology/Cosmology. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World, pp. 107-20. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

SUSAN E. JAMES is a historian who earned her

Ph.D. from Cambridge University in 1977. She has a deep interest in

the culture of the Southwest and has published extensively in the fields

of history, comparative culture, and art.

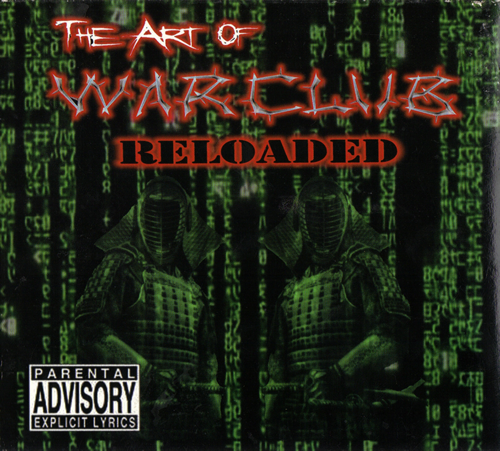

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06