The Atlantic, Sept 1991 v268 n3 p87(11)

The decipherment of ancient Maya. David Roberts.

Abstract: Epigraphers have made important advances

in deciphering Mayan hieroglyphs in recent years. The traditional view

of Mayan civilization and culture is being changed by this research.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1991 The Atlantic Monthly Magazine

FOR ROUGHLY 650 YEARS, FROM A.D. 250 TO 900, Maya Indians, living in

what is today southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and western Honduras

and El Salvador, created the greatest civilization ever to flourish

in the pre-Columbian Western Hemisphere.

Out of the tangled jungle, among the ceiba and mahogany trees, sprang

Tikal, with its 3,000 structures, ten reservoirs, and six temple-pyramids,

including the tallest ancient structure (229 feet) ever found in the

Americas. At Copan--"a valley of romance and wonder," according

to the explorer who rediscovered it in the nineteenth century--the Maya

built an exquisite ball court and a staircase of sixty-three broad steps

covered with inscriptions, and carved scores of vivid sculptures of

gods out of green volcanic tuff. During the 650 years of greatest vitality,

now called the Classic Period, the Maya built some 200 cities. At Palenque

they executed a labyrinthine palace complex festooned with eloquent

stuccos; at Bonampak they created the finest ancient mural paintings

in the New World; at Quirigua they built a stone monument thirty-five

feet high, covered with bas-relief portraits and intricate hieroglyphs.

Their small-scale art was rich and various: jade masks, carved wooden

lintels, bones engraved with delicate vignettes, painted chocolate cups,

ceramic figurines, bowls and pots of stunning design. And in creating

a true writing system, the Maya accomplished something not achieved

by either of the other two preeminent New World cultures, the Aztec

and the Inca.

Abruptly and mysteriously, at the end of the ninth century the great

Mayan civilization collapsed. When the Spaniards came, 700 years later,

the Maya were still linked, intellectually and spiritually, to the Classic

Period. But the conquistadors were more interested in gold and conversions

to Christianity than in ancient cities. The devastations of war, slavery,

and disease killed 90 percent of the Maya. In the wake of this genocide

most surviving links to the Classic Period were severed.

The rediscovery of this vanished ancient culture dates from the daring

explorations of an American lawyer named John Lloyd Stephens and an

English artist named Frederick Catherwood, who prowled through Central

American jungles from 1839 to 1842. Catherwood's skillful engravings

showed scores of upright stone slabs, or stelae, whose surfaces were

crowded with columns of strange but suggestive symbols. Stephens's books

about his explorations with Catherwood became best sellers, and curiosity

about this lost Mayan glory seized the public imagination.

The survival of the carved hieroglyphs, on hundreds of stelae moldering

in the jungle, promised a rich understanding of the ancient city-builders.

Musing on Copan, Stephens wrote, "One thing I believe, that its

history is graven on its monuments. . . . Who shall read them?"

Scholars soon struggled to decipher the arcane writing system, but a

century's toil produced almost nothing in the way of useful translation.

A leading German expert, Paul Schellhas, predicted gloomily that the

Mayan glyphs would never be deciphered.

Meanwhile, the leading archaeologists wove a supposedly comprehensive

explanation of Classic Mayan civilization. Finding almost no evidence

of defensive structures among the ruins of the great cities, these scholars

concluded that the Maya were a peaceful, philosophical culture. Sylvanus

Morley, an American expert who died in 1984, deduced that the Old Empire

spread outward from such sites as Tikal and Copan during Classic times;

after the collapse the Maya moved north and established a New Empire

in Chichen Itza and other sites in the Yucatan. J. Eric Thompson, an

English archaeologist, doubted that the great ruins were cities; calling

them "ceremonial centers," he postulated that they had been

largely vacant, reserved for priests who were devoted to the worship

of time.

These theories, we now know, were dead wrong.

The Egypt Analogy

AS LATE AS 1960 ONLY A FEW MAYAN GLYPHS HAD been deciphered. In the

years since then, however, the decoding of Mayan writing has finally

begun in earnest. During the past decade the enterprise has gathered

momentum, and in the past two or three years some of the most important

decipherment yet accomplished has taken place, thanks to the work of

a handful of young epigraphers, most of them from the United States.

Their toil is so frenetic that they have almost no time to publish.

In a zealously collaborative mission they trade discoveries by way of

late-night phone calls, letters dashed off on airplanes, hallway bull

sessions at professional conferences.

An obvious analogy is the reappraisal of ancient Egypt. Napoleon's short-lived

conquest of the Nile Delta, in 1798, spawned a popular interest in Egyptology.

Ignored for centuries, one of the most magnificent civilizations of

antiquity began to emerge from the shadows. The pyramids and the Sphinx

became the universally familiar icons they are today. Among the booty

hauled away from ancient sites were the twin obelisks called Cleopatra's

Needles (one ended up in London, the other in New York), a pink obelisk

from Thebes that stands today in Paris's Place de la Concorde, and a

curious stone of black fine-grained basalt, carved with writing in three

languages, found at Rosetta, east of Alexandria.

Since the Renaissance, antiquaries, travelers, and scientists had puzzled

over the colossal ruins strewn across the sands of the lower Nile. Yet

by 1820 little more was known about the Egypt of the pharaohs than what

had come down as hearsay in fragmentary Greek and Roman sources. The

key to the hieroglyphic script of the ancient Egyptians had been lost

around A.D. 400.

In this scholarly desert farfetched deductions by savants took root.

The pyramids, they concluded, were either observatories or a stone allegory

wrought by a Christian God. China had once been a colony of Egypt. Nothing

of the true history or religion of the ancient Egyptians, none of the

names of their kings or details of their wars, was known.

Then, in 1822, an out-of-work history teacher named Jean-Francois Champollion

made one of the great intellectual breakthroughs of the century. Ruminating

over the Rosetta Stone--which he suspected displayed parallel texts

in Greek characters, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and Demotic, a cursive

version of Egyptian--the young Frenchman stumbled on the key to decipherment.

His crucial insight was that the hieroglyphs were not pure logographs

(symbols each of which stands for a different word) but were in large

part phonetic (symbols standing for syllables, which could be combined

to form many different words). From Champollion's font has sprung a

flood of modern knowledge about the civilization of the Ptolemies, the

Ramessides, Tutankhamen, and Cleopatra.

The ancient Maya are in many respects the New World equivalent of the

Egyptians. And as Linda Schele, a University of Texas art historian

and one of the best young epigraphers, puts it, "In Mayan studies

this is the time of Champollion. This will never happen again--never,

ever."

The Mayan Experts

NO MAYAN EPIGRAPHER HAS MADE A GREATER contribution than David Stuart.

A shy, slender twenty-six-year-old graduate student at Vanderbilt, in

Nashville, Stuart seems laid back, almost dreamy, compared with his

colleagues, who are notorious for their manic intensity. On a withering

95[degrees] day several months ago, Stuart stood in a clearing in the

virgin rain forest of northern Guatemala and "read" a fallen

stela to me.

"That's the verb 'to adorn," Stuatt said, pointing to a glyph

that had been carved in soft limestone more than 1,200 years ago. "The

bound captive is Jaguar Claw, who was the ruler of Seibal." Stuart

stepped back to look at a whole sentence. "Six days after the war

event with Seibal,'" he recited, "Jaguar Claw, the holy lord

of Seibal, was adorned.' For sacrifice, that is. They dressed him up

before they put him to death. "A defeated Mayan king, the epigraphers

have shown, was held captive for as long as several years, tortured,

costumed and prettified, forced to play a ball game that he was preordained

to lose, and then often beheaded. The bizarre sadomasochistic rituals

of warfare between kings, which the ancient Maya apparently practiced

instead of the wholesale slaughter of one city by another, is one of

the many areas of Mayan life to which the epigraphers have brought dazzling

new insights.

Stuart walked a few yards to another stela lying in the grass. Like

the first slab, this one featured an elaborately decorated king standing

on the back of a bound captive. Stuart pointed to a marginal detail.

"See the heron with a fish in its mouth? It may be a play on words,

because the Maya word for 'heron' is the same as the word for 'captive.'

It's like a rebus: the Maya are using a picture of one thing to represent

another."

Later, Stuart pointed out a single glyph on the round surface of an

altar. "We can't decipher it, because this is the only known instance

of the glyph." He stared at the anthropomorphic carving and muttered,

half to himself, "I know it's a verb." Why? "Because

it comes right after the date, and right before a name."

The place is called Dos Pilas. Stuart is part of a multidisciplinary

Vanderbilt team headed by Professor Arthur Demarest, whose six-year

investigation of sites near the Pasion River represents one of the most

ambitious Mayan field projects under way. The team has made spectacular

finds, including a previously unknown ruin on a peninsula jutting into

a lake. The ruin is guarded by a moat forty feet deep, whose unusual

structure promises to revise ideas of Mayan warfare.

Dos Pilas is not an easy place to work. To get to it you must drive

two hours on a bone-jarring rut of a road to Sayaxche (a frontier town

out of Conrad), ride for ninety minutes in an outboard-powered canoe

up a tributary of the Pasion, and then hike for three hours through

the jungle. In December of 1989 an overeager Dutch tourist died of heat

exhaustion in the course of this hike; the locals who hauled his body

out left a cross made of mule bones as a memento mori. The rain forest

here is lush and steamy, full of the cries of exotic animals and insects.

Wander a few feet off the trail, and you may easily get lost. A year

ago a scientist and his Guatemalan guide spent nine hours, without water,

lost in this wilderness. Before they managed to reorient themselves,

they stumbled upon a previously unknown Mayan cave, chock-full of sacred

ritual pottery.

The Vanderbilt base camp is near a stronghold of Guatemalan guerrillas,

who for the past sixteen years have waged a bitter war against one government

after another. Even as Stuart read the stelae to me, a gun battle that

cost several lives was taking place a few miles away. The rain forest

here abounds with snakes, including the deadly fer-de-lance; for all

work off the trail, team members must wear fiberglass leggings, which

have already saved the life of one Dos Pilas laborer. Shortly before

my visit a dig at Rio Azul, to the northeast, had to be shut down after

a Guatemalan worker was bitten by a fer-de-lance. Rushed to the hospital,

he had had his leg amputated, and barely survived.

But Dos Pilas is an epigrapher's delight. Only a month before my visit

the Vanderbilt team had unearthed a hieroglyphic stairway, a series

of broad stone steps with pristine glyphs carved on the risers. Remarkably,

a wall of prehistoric rubble runs perpendicularly across the inscriptions.

Nothing like such a juxtaposition has ever before been found at a Mayan

site. Demarest believes that the hastily built wall, which encircles

Dos Pilas, is evidence of a desperate late state of occupancy. For centuries

before that stage, a stylized combat fought largely by kings and chosen

warriors had kept the balance of power among dozens of rival city-states

in a precarious equilibrium. Death and destruction were held to a minimum.

If Demarest is right, near the end of the Classic Period the rules governing

that combat broke down; warfare began to involve full-scale attacks

on cities, devastation of agricultural fields, and far more killing

and death. The rubble wall at Dos Pilas bespeaks the terror of a people

in fear of annihilation.

Stuart paused before the staircase, from which, within a few weeks,

the rubble wall would be carefully removed. Summarizing the visible

glyphs, he said, "Ruler One put this up. It has to do with a war

against Tikal. All the really interesting part--the who, what, and where--is

under the rubble. All we've got now is the when."

Among the eight or ten epigraphers who are in the vanguard of Maya decipherment,

David Stuart is generally conceded to be the most talented. Demarest,

his faculty adviser at Vanderbilt, says, "All the others have to

work incredibly hard to make a decipherment. David just seems to do

it effortlessly. I've been there when he's read an inscription just

as it's been brushed off of the first time."

Indeed, though he would blush at the analogy, Stuart seems to be a kind

of Mozart of epigraphy. The son of Mayan archaeologists, he grew up

surrounded by glyphs and potsherds. "The joke," a colleague

says, "is that one of david's first words was Dzibilchaltun"--the

name of the dig in the Yucatan where his father was working when David

was an infant. Stuart's earliest memory is of a family trip to archaeological

sites all over Mexico. Later, at age eight, he sat mesmerized at the

Mayan site Coba, staring at glyphs and at the drawings epigraphers had

made of them.

"I was absorbed even then by the visual complexity of the glyphs,"

Stuart says drily. He presented his first paper at age twelve. Its title,

"Some Thoughts on Certain Occurrences of the T565 Glyph Element

at Palenque," already bore the stamp of reticence that has come

to be his trademark. "Early on," Linda Schele says, "people

wanted to dismiss what David was doing, because he was so young."

At eighteen Stuart received a five-year MacArthur "genius"

grant; he is the youngest person yet to have been so honored. The media

bombarded him with the kind of attention normally lavished on movie

stars and athletes, an experience that still makes him wince. "I

don't like the term 'whiz kid,'" he says softly. The wonder is

that Stuart did not develop a celebrity's ego. "The MacArthur could

have been very unhealthy for him," says Stuart's closest colleague,

Stephen Houston, a professor at Vanderbilt. "I give a lot of credit

to David's parents. They're very down-to-earth people."

At the time of the Spanish conquest, astonishingly, the Maya were still

writing glyphs--not on stone stelae but in handmade books. A treatise

written by Friar Diego de Landa in the Yucatan in 1566 contains a passage

that haunts every Mayanist:

These people also used certain characters or letters, k with which they

wrote in their books about the antiquities and their sciences. . . .

We found a great number of books in these letters, and since they contained

nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them

all, which they most grievously, and which gave them great pain.

The Mayan books were made of long pieces of fig-bark paper, plastered

with gesso and folded screen-fashion, like the bellows of an accordion;

the covers were made of jaguar skin. The "letters" were drawn

by master scribes in black and red paint, with fine-haired brushes.

The manuscripts that Landa and his fellow Franciscans burned bore the

exquisite calligraphy of a tradition at least a millennium and a half

old.

Not all the Mayan books vanished in the fires. Some of them found their

way to Europe as part of the Royal Fifth, the share of booty that Cortes

sent to Charles V. The fig-paper books were puzzled over by scholars

in Seville and Valladolid, and Albrecht Durer may have seen them in

Brussels. But Europeans could make nothing of these strange productions.

Over the years their fragile paper crumbled into dust, and many were

likely thrown out as trash. By the nineteenth century, when Mayan writing

was rediscovered, fragments of only three books survived in Europe,

one each in Dresden, Paris, and Madrid.

This trio of texts, along with the stelae rediscovered by Stephens and

Catherwood, were all that scholars had to work with when they began

to puzzle over Mayan writing, in the 1840s. By then the direct descendants

of the builders of Copan and Chichen Itza and Tikal had completely lost

the knowledge of how to read the glyphs. The murderous Spanish conquest

had claimed the life of virtually every member of the elite class, probablky

the only Maya who could write.

A few secrets of the language were solved early, such as the Mayan number

system, the workings of the culture's dazzling precise calendar, and

the glyphs for certain gods and animals. But for half a century after

1990, work on the decipherment of Mayan glyphs remained virtually stalled,

despite the concerted efforts of a succession of brilliant scholars.

The basis structure of the writing proved so intractable that as late

as 1960 the script remained, in the words of one expert, "mute

and unread." Some of the best minds in Mayan studies despaired

of further progress; many agreed with Paul Schellhas that the writing

would never be deciphered.

In general, steady progress on undeciphered scripts is by no means inevitable.

From the Etruscans, who lived in Tuscany before the Romans, we have

some 10,000 inscriptions, perhaps twice as many as we have from the

Maya. Yet only a few Etruscan words can be read. In the early 1950s,

when an amateur epigrapher named Michael Ventris deciphered Linear B,

the ancient Mycenaean language discovered in Crete, his feat made headlines.

A parallel script found on neighboring tablets, Linear A, the Minoan

language of Crete, remains uncomprehended. Iberian, the pre-Roman writing

from Span; Sinaitic, an apparent precursor of Hebrew; Archaic Sumerian,

the earliest written language in the world; Mohenjo-Daro, from the Indus

Valley; futhark runes, from Scandinavia; Elamite, from Iran; the very

earliest Egyptian hieroglyphics--all these and other major writing systems

remain undeciphered, with no breakthroughs in sight. In the case of

Rongorongo, found on wooden tablets from Easter Island, experts cannot

even agree on whether the characters are a true language or simply a

set of mnemonic symbols used to remind singers of ritual chants.

With only hints from the hieroglyphs, the archaeologists influenced

by Sylvanus Moley and Eric Thompson sketched out their compelling portrait

of the peaceful, priest-ruled, time-obsessed Maya. In 1950 Thompson

summed up his view of Mayan writing in a famous passage:

I conceive the endless progress of time as the supreme mystery of Maya

religion, a subject which pervaded Maya thought to an extent without

parallel in the history of mankind. In such a setting there was no place

for personal records, for, in relation to the vastness of time, man

and his doings shrink to insignificance. To add details of war or peace,

of marriage or giving in marriage, to the solemn roll call of the periods

of time is as though a tourist were to carve his initials on Donatello's

David.

Younger scholars today tend to snicker at the Morley-Thompson notion

of the pacific, calendar-happy Maya. Linda Schele and her co-author

Mary Miller write, "The Maya were considered the Greeks of the

New World, and the Aztecs were seen as Romans--one pure, original and

beautiful, the other slavish, derivative and cold." But, like other

pioneers later proved wrong, Morley and Thompson made reasonable inferences

from limited data. The ancient Maya, we now know, were an exceedingly

aggressive and warlike people: in Schele's pithy phrase, "blood

was the mortar" of their society. "Man and his doings"

were of paramount interest to them--so much so that the stelae boast

vaingloriously about the great deeds rulers performed. Rather than living

in a huge empire like Rome's, the Maya were spread across a balkanized

land of feuding peoples, like the West of the Native Americans before

the white man came.

The Fruit of Early Efforts

THE HALLMARK OF MAYAN ART IS INTRICACY OF ornamentation. The designers

of the stelae--and of carved jade plaques and wooden lintels, incised

bones and seashells, painted murals and pots--abhorred blank space.

The term "baroque" has often been invoked. To the naive eye

Mayan iconography has the dazzling but unfathomable busyness of, say,

the stuccoed walls of the Moorish Alhambra.

The same crowded richness of detail characterizes Mayan writing. Each

hieroglyph occupies a pre-allotted cubicle on the stone's surface; we

know from unfinished inscriptions that the carver blocked out a grid

of squares before filling in the words. The glyphs are arranged in pairs

of vertical columns, which the ancient Maya read left to right, top

to bottom.

The only readily accessible feature of Mayan glyphs is the number system,

which a tourist can master after a week of looking at monuments. The

Maya used a system based on the number twenty, with only three symbols:

a bar for five, a dot for one, and a stylized shell for zero. Neither

the Greeks nor the Romans were able to conceive of zero and used it

as the basis of a numerical place system, an intellectual discovery

with profound consequences for cultures that made it. In the Old World

only the Hindus or perhaps the Babylonians before them made this breakthrough.

The Mayan discovery of zero was obviously independent of the Hindu or

Babylonian.

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the immensely elaborate Mayan calendar

was still being used by astrologer-priests to divine the future and

meditate upon the past. Thanks to that fact, Mayan dates can be precisely

correlated with the Gregorian calendar. On most stelae the hieroglyphic

inscription begins with the date of the stone's dedication, recorded

in a five-number sequence called the Long Count. Thus we know, for instance,

that Stela 11 at Piedras Negras, Guatemala, was dedicated on August

22, A.D. 731.

The earliest firmly dated Mayan monument is Stela 29 at Tikal, with

a date of A.D. 292. The most recent monument date yet found is A.D.

909. This span of 600-plus years covers the golden age of Mayan culture,

when most of the great cities were built. Indeed, one definition of

the Classic Period is the age during which monuments were dated by the

Long Count.

By working backward, scholars figured out that the Mayan calendar numbered

from a Day Zero--August 13, 3114 B.C. This was considered the beginning

not of the world, however, but only of the current cycle of a perhaps

infinitely ancient universe. Their flexible number system allowed the

Maya to conjure with unimaginably distant dates. A stela at Quirigua

is inscribed with a date 400 million years in the past. What this means,

nobody knows.

Around A.D. 900 the most advanced civilization the New World had ever

seen suddenly collapsed. The causes of this breakdown constitute the

greatest unsolved problem that Mayanists confront. After A.D. 909 the

Maya erected no more carved stelae that have been found and seem to

have raised few new temples, let alone cities, except in the northern

Yucatan, at such sites as Chichen Itza and Tulum.

By the 1540s, owing to the ruthlessness of the conquistadors, the Maya

in the Yucatan and the Guatemalan highlands had submitted to Spanish

rule. One group, however, the proud and canny Itza, retreated to a fabled

lake deep in the Peten, a jungle wilderness in northern Guatemala, where

they build an island capital called Tayasal. For a century and a half

Spanish expeditions thrust inland toward Tayasal; some explorers met

their deaths in Itza ambushes. But finally, in the period 1695-1697,

the Spaniards reached the lake and conquered Tayasal.

The pivotal figure in this conquest was Padre Andres de Avendano y Loyola,

one of the most extraordinary men ever to appear in Spanish America.

Avendano turned the tide of Itza resistance by convincing the defenders

of Tayasal, to their astonishment, that their own calendrical prophecies

predicted a major upheaval in 1696. He was able to perform this feat

because, unique among Europeans, he had learned to read Mayan hieroglyphs.

Avendano's brief account of the conquest of Tayasal alludes to another

treatise he had written, explaining the decipherment; this book, alas,

is lost to history.

As late as the beginning of the eighteenth century a few Mayan sages

(and one Franciscan friar) could still read the glyphs. But the tradition

of literacy among the Maya was utterly severed by the annihilation of

the elite class, completed at Tayasal, and today knowledge of the glyphs

among the Maya is extinct.

The Landa Treatise and Further

Developments

WITHOUT THE ROSETTA STONE, CHAMPOLLION could not have deciphered Egyptian

hieroglyphs. The closest thing to a Rosetta Stone for Mayan glyphs comes

on a single page of a treatise written by Diego de Landa, the book-burning

friar. Called before a Spanish court to defend his harsh treatment of

the Maya, Landa wrote his Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan in 1566.

Lost for centuries, the book was rediscovered by a Flemish priest in

the 1860s. According to its English translator, William Gates, 99 percent

of what we know about the Maya at the time of the conquest derives from

Landa.

One day in Merida, Landa asked one of the last literate Maya, a man

named Gaspar Antonio Chi, to write down the Mayan "alphabet"

in glyphs. With the inevitable naivete of a sixteenth-century European,

Landa assumed that the basic building blocks of Maya were alphabetic

letters, as is the case in Spanish and all other European languages.

Ancient Maya, however--like Chinese, ancient Egyptian, and many other

languages--has no alphabet: the very concept of a letter is foreign

to it.

Gaspar Antonio may have tried to explain this fact to Landa, but the

friar could not understand: all languages, he assumed, had alphabets.

Grumbling as he performed the task, the Mayan gave Landa something similar

to an alphabet but crucially different. Four centuries would intervene

before scholars could discover exactly what Gaspar Antonio had delivered

to the demanding Franciscan.

In the meantime, as they pored over the intricate glyphs, students of

the lost language tacitly made a pivotal but erroneous assumption. The

glyphs look like stylized pictures: you can see a jaguar's head here,

a bird's foot there, a human profile elsewhere. More-abstract glyphs,

it was assumed, were pictures that had been simplified and stylized

over the centuries. The erroneous assumption was that Maya was a purely

logographic language: that is, each glyph stood for a word.

The first real breakthrough came in 1952, in the work of an obscure

Soviet linguist named Yuri Knorosov. Pondering Landa's alphabet, he

became convinced that the glyphs Gaspar Antonio had drawn represented

neither letters (as Landa thought) nor words (as all Mayan scholars

assumed) but styllables. Landa had asked his informant to draw the letter

B, but he must have pronounced the letter beh, as the Spanish do. Gaspar

Antonio, then, had written what Knorosov guessed--correctly--was the

glyph for the Mayan syllable beh. In a tour de force of reasoning, Knorosov

made a number of phonetic decipherments. For instance, Knorosov showed

that a glyph already suspected of meaning "turkey" was a compound

of two syllabic glyphs, ku and tzu. In a dictionary of modern Yucatec

Maya, Knorosov found "turkey" glossed as kutz. (Today's Maya

speak at least thirty-one different languages, most of them mutually

unintelligible. A few, including Chol and Yucatec, turn out to resemble

closely the written language of the ancient Maya.)

Most Western Mayanists refused to accept Knorosov's radical notion that

the glyphs were in part phonetic. The Russian's work, unfortunately,

was riddled with wild errors, as well as insightful discoveries, and

filled with sneering Marxist-Leninist rhetoric. Knorosov had never seen

a Mayan site. Instead, he had analyzed facsimiles of the three surviving

Mayan books in Europe. Eric Thompson, with a sneering rhetoric of his

own, ridiculed Knorosov into limbo. During the 1950s and 1960s only

a couple of Mayanists kept the Russian's seminal premise alive.

In 1958 a Mexican scholar, Heinrich Berlin, announced another major

discovery. By examining similar glyphs in scores of different contexts,

he deduced that a certain kind of glyph must refer either to a place

(a Mayan city) or to its ruling dynasty. These signposts he called emblem

glyphs. They were the first strong hint that, contra Thompson, the inscriptions

were not limited to "the endless progress of time." The coup

de grace to Thompson's theory came at the hands of a colleague at the

Carnegie Institution, in Washington. In 1960 Tatiana Proskouriakoff,

after mulling over dates from seven sets of stelae at Piedras Negras,

pointed out that within each set all the dates fit into a human lifespan,

and that the span of dates in a set often overlapped those in one or

two other sets. She concluded that the inscriptions recorded not astronomical

musings but the births, enthronements, and deaths of kings and their

heirs. The evidence Proskouriakoff marshaled was overwhelming, and proved

that Mayan inscriptions were primarily historical.

According to Peter Mathews, of the University of Calgary, who had the

story from Proskou7riakoff herself, she walked down the hall and gave

the manuscript of her groundbreaking paper to Thompson, then the most

respected Mayanist in the world. He glanced at the argument and told

her that it couldn't possibly be true. The next day he handed the paper

back to her, saying, "You're absolutely right." To his credit,

Thompson acknowledged Proskouriakoff's discovery in print, even thought

it contradicted much of his life's work.

The Dual Role of Glyphs

DECIPHERMENT HAS ALWAYS BEEN A GREAT field for amateurs. Champollion

was an unemployed history teacher, Michael Ventris an architect. Proskouriakoff

also trained as an architect. Even today, amid the collaborative ferment

of Maya decipherment, prescribing the ideal training for an epigrapher

would be difficult. According to one of the best, a twenty-seven-year-old

German from the University of Bonn named Nikolai Grube, "A good

epigrapher needs to have excellent training in linguistics, needs to

know both Chol and Yucatec Maya, and should know Spanish well. He must

also have an excellent visual memory." Grube taught himself cuneiform

writing and David Stuart learned Chinese, each to aid his work in Maya.

Yet some of today's decipherment stars do not fit Grube's formula. Linda

Schele, for example, was teaching studio art in Alabama when she went

as a tourist to Palenque, where the riddle of the Maya caused her to

plunge passionately into a new career.

Some uncanny mixture of intuitive insight and logical clarity seems

to animate the best epigraphers. The field has become highly technical,

yet computers play almost no part in it. By now about 800 different

Mayan glyphs have been identified. A good epigrapher not only knows

all 800 by heart but knows virtually every context in which each appears.

Several months ago Stuart walked into the museum at Tikal and saw a

photo of a looted artifact recently recovered by Guatemalan authorities.

He stared, mesmerized, at the photo, and murmured, "This is too

much. See that jaguar in the center? It's actually a glyph--the name

of someone. It occurs at Piedras Negras and at Yaxchilan." Stuart

carries in his head a card catalogue of thousands of different Mayan

texts, which he flips through effortlessly to find the previous appearances

of a single glyph.

To make a new decipherment, someone like Stuart essentially marshals

a series of "if-then" syllogism, drawing upon the known texts

in Mayan books and on stelae, pots, and lintels. If this glyph is a

verb, then it will appear just before a glyph that is a noun (word order

is not the same in Maya as it is in English). If the glyph on one stela

refers to the accompanying picture of a king, then what does it tell

us that the same glyph is associated with a different picture on another

stela? And so on. Even a simple decipherment is difficult to explain

to a lay reader, so thorny and subtle is the chain of reasoning. Nearly

all decipherments are at first tentative, and many fail the test of

further verification. Yet when a decipherment clicks, it unleashes a

tide of corroboration. These are the moments an epigrapher lives for.

No single discovery in the past twenty years has had the impact of Knorosov's,

Berlin's, and Proskouriakoff's great intuitive leaps. Progress has come

in thousands of tiny increments. The approach that has yielded the most

vivid results is the search for glyphs that represent phonetic syllables.

It is reasonable to assume that ancient Maya was composed of the same

nineteen consonant sounds and five vowel sounds as the several Mayan

languages spoken today that closely resemble it. This hypothesis allows

scholars to construct what they call a syllabary--a chart of all the

possible syllables in the language.

The ch sound in Maya, for instance, matched with the five vowel sounds

(a, e, i, o, u), produces five syllables, sounded as cha, che, chi,

cho, and chu. In ancient Maya there should be a total of ninety-five

(five times nineteen) possible syllables. The challenge for epigraphers

is to identify ,the glyph that stands for each of those ninety-five

syllables. So far, for example, the glyphs for cha, che, chi, and chu

have been identified, but cho is still out there on the loose. Every

year epigraphers nail down a few more syllable glyphs, and by now teh

syllabary is more than half full.

Mayan glyphs can be either logographic or phonetic--that is, they can

stand either for a word or for a syllable. In Maya you can often write

a word in two different ways, by giving the unique logograph for the

word or by "spelling it out" in syllables. The great power

of a phonetic decipherment is that it tells us not only what the word

means but also--if the assumption about enduring pronunciation is correct--how

it sounded in the seventh century. For some time now epigraphers have

recognized the glyphs that identify most of the rulers of Tikal. To

refer to these ancient despots, they make up names like Curl Nose and

Stormy Sky and Shield Skull. Such nicknames are playful shortland descriptions

of the glyphs: the glyph for one of the men who reigned over Tikal in

the seventh century looks like a design conjoining a shield and a skull.

We have no idea, however, how the Maya pronounced the glyph we refer

to as Shield Skull. But when David Kelley, of the University of Calgary,

discovered that a ruler of Palenque whom epigraphers had dubbed Hand

Shield was also named in phonetic glyphs, Kelley learned that the ruler's

people had called him Pacal. For the first time the true name of a Mayan

king was revealed to us.

Though late in life Eric Thompson reluctantly granted the historicity

of Mayan inscriptions, he never accepted phoneticism; he refused to

believe that glyphs could represent syllables as well as whole words.

Surprisingly, both Berlin and Proskouriakoff balked on the same question.

Shortly before he died, Berlin told Linda Schele, "I must admit

that it works. But I'm too old to learn all this new stuff."

The quest for decipherments is made infinitely more difficult by the

huge variability of the Mayan scripts. One problem is to recognize stylistic

differences between carvers or scribs--in the way that a reader of English

can recognize the same word in two quite different specimens of handwriting.

But the ancient Maya loved to play with language for its own sake. Any

given glyph may appear, as Schele points out, "in either abstract

or personified form, which in turn can be either anthropomorphic or

zoomorphic and in head or full figure form." On top of this, each

glyph-square may contain as many as nine signs, and the curlicues and

squiggles that hang like barnacles on the most prominent sign may be

affixes that modify its meaning or they maybe independent signs, made

to appear subordinate just because the Mayan carver liked the looks

of it that way.

Written Maya has been revealed to be grammatically and syntactically

rich and strange. The normal word order is verb-object-subject, as if

we said, "Wrote the book he." The language boasts such nuances

as tense and aspect, multiple affixes, and a pattern called the ergative,

in which the choice of pronoun depends on the transitivity of the verb.

To make matters even knottier, the Maya were demon punsters.

What We Now Know About the Maya

EPIGRAPHERS ARE FREQUENTLY ASKED WHAT PERCENTAGE of the Mayan glyphs

have been deciphered. The question itself is ill defined. Often epigraphers

have a good idea of a glyph's meaning; they can say something like "This

glyph means birth." But the ultimate goal of decipherment is to

be able to understand the glyphs as the Maya did. To use ancient Greek

as an analogy, we want not only to know the story of Odysseus's return

to Ithaca but also to be able to read every line of the Odyssey out

loud. "For about seventy-five percent of the glyphs we have an

idea what the Maya were talking about," Nikolai Grube says. "But

so far we can read and pronounce only about forty percent as the Maya

did." David Stuart makes an even lower estimate: around 25 or 30

percent.

How has the partial decipherment transformed our understanding of the

Classic Maya? One must preface any answer with a caveat. In burning

the invaluable fig-paper books the Franciscans committed an unforgivable

crime. As Kathryn Josserand, a Florida State University Mayanist, says,

"Imagine what future archaeologists would know of American life

if they had only the inscriptions on monuments in Washington, D.C."

The texts on the best Mayan stelae, to be sure, are rich and eloquent.

The three Mayan books in European libraries are all concerned with ritual

astronomial matters. We know, however, from Spanish accounts, that Mayan

books also dealt with history, genealogy, songs, prophecies, and what

the friars called science. The Quiche Maya epic the Popol Vuh, which

was written in highland Guatemala in the 1550s by bards whom the friars

had taught to write in Maya transliterated into roman letters, is a

mythic narrative so powerful and poetic that it magnifies the tragedy

of the lost literature.

In 1971 a fig-paper book appeared out of nowhere at an exhibit at the

Grolier Club in New York. How it got there remains a murky business,

but most students believe that the book was retrieved from a dry cave

in Chiapas by a looter and sold to a Mexican collector. Several authorities,

including Thompson and the Mexican government, thought the Grolier Codex

a fake, but it has since been carbon-dated to A.D. 1230 and proved genuine.

Unfortunately, this fourth known Mayan book is in bad shape, and what

can be read of it concerns only calculations of the cycle of Venus.

Limited though the carved inscriptions may be, epigraphers have wrung

from them knowledge that immeasurably deepens, even revolutionizes,

our grasp of the Classic Maya. Perhaps most important, the glyphs appear

to lay to rest for good the Morley-Thompson notion of a peaceful, contemplative

civilization. On the evidence, the Maya were every bit as bloody and

warlike as the Aztecs. Their rulers validated their regins and celebrated

the completion of time cycles through ritual bloodletting: kings pierced

their penises with stingray spines, queens ran barbed ropes through

holes in their tongues. Graphic depictions of these gruesome rites appear

on monuments that were known by the nineteenth century, but Mayanists,

influenced by conventional wisdom, resisted their implications. What

we now believe to be dripping blood, they saw as water. In 1899 the

pioneering investigator Alfred Maudslay published a drawing of a Yaxchilan

lintel which deliberately omitted the tongue-rasping rope with which

a queen mutilated herself.

Gone, too, with the new decipherment, is any vestige of Morley's Old

and New empires. The Maya apparently never confederated; they always

lived in feuding citystrates, and their stelae repeatedly celebrate

the victories of one over another. At least until the last century and

a half before the collpase, warfare was a highly stylized business.

One of the great mysteries of the Classic Period was a span of roughly

160 years that has come to be called the Tikal Hiatus. Archaeologists

had observed that a Tikal, the greatest of all Mayan cities, no monuments

were raised from A.D. 534 to 690. The cause of that gap remained a matter

for conjecture until 1986. Working in a ball court at Caracol, a site

in Belize some forty miles southeast of Tikal, Diane and Arlen Chase,

of the University of Central Florida, unearthed a pristine glyph-covered

altar. Diane ran back to camp to get Stephen Houston, the project epigrapher.

Reading the altar, Houston found that it documented Caracol's victory

over Tikal in 562, and its subsequent 140 years of domination over its

grander neighbor.

As Nikolai Grube puts it, "Nobody had ever believed that Tikal,

this great city, could have been defeated by anyone else." The

Chases and Houston's discovery is one of the triumphs of Mayan epigraphy.

A major war and consquest, otherwise lost to archaeology, became known

through one reading of glyphs, and with that reading one of the chief

puzzles about the Classic Period was solved.

At the best-documented sites epigraphers have been able to put together

dynastic sequences of kings. From A.D. 292 to 869 at Tikal, we have

a well-dated roster of twenty-seven rulers, twenty-three of whose name-glyphs

we can recognize. More and more, the personalities of some of these

jungle despots emerge. As Linda Schele has written,

The ancient Maya have become a historical people. . . . Perhaps one

day the names of . . . Pacal of Palenque, Yax-Pac of Copan and Ah Cacaw

of Tikal will take their place next to the names of Ramses of Egypt,

Darius of Persia and Perikles of Athens, as we teach our children the

history of the world.

On a number of important matters the inscriptions shed no light. They

tell us nothing whatsoever about the Mayan economy and trade, subjects

that linger in a lacuna of ignorance. On the other hand, decipherment

has begun to penetrate some of the more sophisticated corners of ancient

Mayan thought. In a landmark 1989 paper Stuart and Houston demonstrated

that an oft-occurring glyph, catalogued as 539, was pronounced way and

alluded to the Mesoamerican notion of a "co-essence," "an

animal or celestial phenomenon . . . that is believed to share in the

consciousness of the person who 'owns' it." This powerful decipherment

implies that many of the supernatural figures that used to be called

"gods" or "underworld denizens" by iconographers

are rather to be thought of as mystic doppelgangers to Mayan heroes.

Stuart and Houston were also the first to find Mayan toponyms, glyphs

that unequivocally name geographic places. Stuart showed that the toponym

for Aguateca was a pictographic rendering of "sun-faced split mountain"

-- a perfect description of the eastward-looking site, which is cleft

by a deep crevice in the rock. Stuart made this reading without ever

having visited Aguateca. In a comparable flash of insight, he not only

identified the toponym of a site on a lake in the Peten but also discovered

a phonetic rendering of the toponym which he could read as Yax-ha, which

means "Green Water." Strikingly, today's Maya still call the

site Yaxha. Never before had an epigrapher showed that a Mayan place-name

had remained stable for nearly 2,000 years.

For the foreseeable future epigraphers are unlikely to run out of mysteries

to ponder. The causes of the late-Classic collapse--a calamity as sudden

and a far-reaching as the fall of Rome--remain an enigma. Because monument-carving

ceased--as far as we know--after A.D. 909, we may never have a revealing

record of that Mesoamerican apocalypse. "I'll tell you what they

were worried about," Schele says. "They were worried about

war at the end. Ecological disasters, too. Deforestation. Starvation.

I think the population rose to the limit the technology could bear.

They were so close to the edge, if anything went wrong, it was all over.

"Yet Schele's theory remains only an educated guess.

Other essential mysteries make epigraphers salivate: How and why did

Mayan writing develop? Why was the system successful for so long? How

did the Mayan economy work? How did Mayan civilization differ from one

site to another? Were the gods of Bonampak, for instance, worshiped

also at Copan? How much did the Maya know about the rest of the world?

One of the burning questions at the moment is the extent to which writing

systems other than the Mayan developed in the New World. In 1986 a barefoot

fisherman waded into a swampy river in Veracruz, far to the northwest

of the Mayan domain. Stepping on a flat stone slab, he was surprised

to feel complicated patterns under his toes. When the slab was hauled

out of the river, experts were astonished to find a finely carved stela,

with twenty-one columns of hieroglyphs. More astonishing was the fact

that the glyphs were not Mayan. The carvers, however, had recorded a

pair of Long Count dates that could be read as A.D. 143 and 156--earlier

than any known Mayan monument.

The finding of the La Mojarra stela, as it is called, is "a fabulous

thing," David Stuart says. "I think it will prove to be one

of the milestone discoveries of the last fifty years." Maya was

long considered the only true writing system to have developed in the

New World. Now we know that another written language, perhaps belonging

to the Olmec people, developed more or less independently. Some 400

glyphs are discernible on the stela. Simply on the basis of their variety

Grube speculates that the La Mojarra language may have fewer signs than

Maya, and may thus represent an even more phonetic, less logographic

system. But unless many more carved stones are found in Veracruz, the

glyphs will probably never be read.

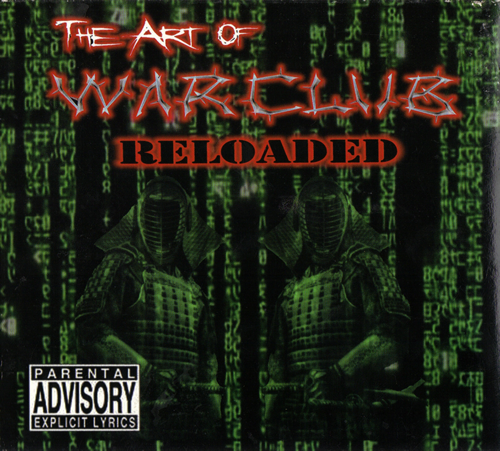

War Club - Riotstage

Hear more War Cub music @

Mexica Uprising MySpace

Add Mexica Uprising to your

friends list to get updates, news,

enter contests, and get free revolutionary contraband.

Featured Link:

"If Brown (vs. Board of Education) was just about letting Black people into a White school, well we don’t care about that anymore. We don’t necessarily want to go to White schools. What we want to do is teach ourselves, teach our children the way we have of teaching. We don’t want to drink from a White water fountain...We don’t need a White water fountain. So the whole issue of segregation and the whole issue of the Civil Rights Movement is all within the box of White culture and White supremacy. We should not still be fighting for what they have. We are not interested in what they have because we have so much more and because the world is so much larger. And ultimately the White way, the American way, the neo liberal, capitalist way of life will eventually lead to our own destruction. And so it isn’t about an argument of joining neo liberalism, it’s about us being able, as human beings, to surpass the barrier."

- Marcos Aguilar (Principal, Academia Semillas del Pueblo)

![]()

Grow

a Mexica Garden

12/31/06

The

Aztecs: Their History,

Manners, and Customs by:

Lucien Biart

12/29/06

6 New Music Videos

Including

Dead Prez, Quinto Sol,

and Warclub

12/29/06

Kalpulli

"Mixcoatl" mp3 album

download Now Available

for Purchase

9/12/06

Che/Marcos/Zapata

T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

7/31/06

M-1

"Til We Get There"

Music Video

7/31/06

Native

Guns "Champion"

Live Video

7/31/06

Sub-Comandante

Marcos

T-shirt Now Available for Purchase

7/26/06

11 New Music Videos Including

Dead Prez, Native Guns,

El Vuh, and Olmeca

7/10/06

Howard Zinn's

A People's

History of the United States

7/02/06

The

Tamil Tigers

7/02/06

The Sandinista

Revolution

6/26/06

The Cuban

Revolution

6/26/06

Che Guevara/Emiliano

Zapata

T-shirts Now in Stock

6/25/06

Free Online Books

4/01/06

"Decolonize"

and "Sub-verses"

from Aztlan Underground

Now Available for Purchase

4/01/06

Zapatista

"Ya Basta" T-shirt

Now Available for Purchase

3/19/06

An

Analytical Dictionary

of Nahuatl by Frances

Kartutten Download

3/19/06

Tattoo

Designs

2/8/06